This chapter covers the Digital Roadmap Initiative, which aims to improve co‑ordination across health settings using digital means. The case study includes an assessment of Digital Roadmaps against the five best practice criteria, policy options to enhance performance and an assessment of its transferability to other OECD and EU27 countries.

Integrating Care to Prevent and Manage Chronic Diseases

10. Digital Roadmaps towards an integrated healthcare system, Southern Denmark

Abstract

Digital Roadmap initiative: Case study overview

Description: In 2020, the Region of Southern Denmark launched the Digital Roadmap towards an Integrated Healthcare Sector initiative. The Digital Roadmap initiative aims to improve co‑ordination across healthcare settings and therefore care for patients, with a specific focus on those living with one or multiple chronic conditions. The initiative comprises several digital care interventions such as TeleCOPD, Telepsychiatry, virtual rehabilitation services and an mHealth app. The Digital Roadmap initiative is classified as a “good practice” intervention as part of European Commission’s Joint Action on implementation of digitally enabled integrated person-centred (JADECARE).

Best practice assessment:

OECD best practice assessment of the Digital Roadmap initiative

|

Criteria |

Assessment |

|---|---|

|

Effectiveness |

Across the six interventions included in the Digital Roadmap initiative, there is evidence to support their positive impact on patient experiences and, in certain cases, outcomes. For example, TeleCOPD has been shown to reduce hospital readmission rates. |

|

Efficiency |

There is limited evidence supporting the efficiency of interventions within the Digital Roadmap initiative. Digital health interventions, in general, have the potential to reduce costs while maintaining care quality for example by reducing patient travel time. |

|

Equity |

The impact of the Digital Roadmap initiative on levels of health inequality is not available. More broadly, digital health interventions have the potential to both widen and reduce health inequalities. |

|

Evidence‑base |

The quality of evidence supporting Digital Roadmap interventions varies from high to low quality depending on the intervention. |

|

Extent of coverage |

The Digital Roadmap initiative is accessible to all users of healthcare in the Region of Southern Denmark, which covers 1.2 million people |

Enhancement options: to enhance the performance of the Digital Roadmap initiative, policy makers should consider proposals outlined in this case study such as building population digital health literacy, undertaking economic evaluations from a societal perspective, and ensuring both patients and providers (i.e. the end users of products) are included in the design of new interventions or updates to current ones.

Transferability: based on publicly available data, it is clear Denmark is a digitally advanced country. Countries with less advanced digital health systems may therefore experience transfer and implementation barriers. Nevertheless, this should not act as a deterrent as interventions that make up the Digital Roadmap initiative – e.g. TeleCOPD – are common in countries across the OECD and Europe, and not just those that are digitally advanced. The transferability potential of the Digital Roadmap initiative will be tested as part of JADECARE.

Conclusion: The Digital Roadmap initiative in the Region of Southern Denmark comprises several digital health interventions to improve the access to and quality of healthcare. The evidence suggests the initiative improves patient experiences and, in some cases, outcomes, however, its impact on costs (efficiency) and equity is less clear. The Digital Roadmap initiative has greater transfer potential to countries digitally advanced healthcare systems however this should not be considered a pre‑requisite.

Intervention description

In recent years, the Danish healthcare system has invested heavily in digital technology, as evidenced by its Digital Health Strategy (2018‑22). The Strategy, co-developed by the Ministry of Health, the Ministry of Finance, the Danish regions local governments, focuses on “digitisation and use of health data in the context of prevention, care and direct treatment” (Danish Ministry of Health et al., 2018[1]).

In line with the Digital Health Strategy, the Region of Southern Denmark, in 2020, launched the Digital Roadmap towards an Integrated Healthcare Sector initiative (hereafter, the Digital Roadmap initiative). The Digital Roadmap initiative aims to improve co‑ordination across healthcare settings and therefore care for patients, with a specific focus on those living with one or multiple chronic conditions (European Commission, 2018[2]; Region of Southern Denmark, 2021[3]).

The Digital Roadmap initiative brings together agreements and standards, which make up the foundation for cross-sectoral digital communication in health (European Commission, n.d.[4]; Region of Southern Denmark, 2021[3]).

The Health Agreement: A regional political agreement that details co‑operation strategies between the Region of Southern Denmark, the municipalities and general practitioners. The agreement details strategic objectives such as focusing on prevention initiatives and continuity of care for patients and the elderly.

National digital communication standards: Standards for digital communication and handling of healthcare related data across sectors standardised and supported by an IT-infrastructure implemented throughout the Danish healthcare sector.

The SAM: BO Agreement: A regional co‑operation agreement for cross-sectoral care and to ensure integrated patient experiences such as patient care pathways.

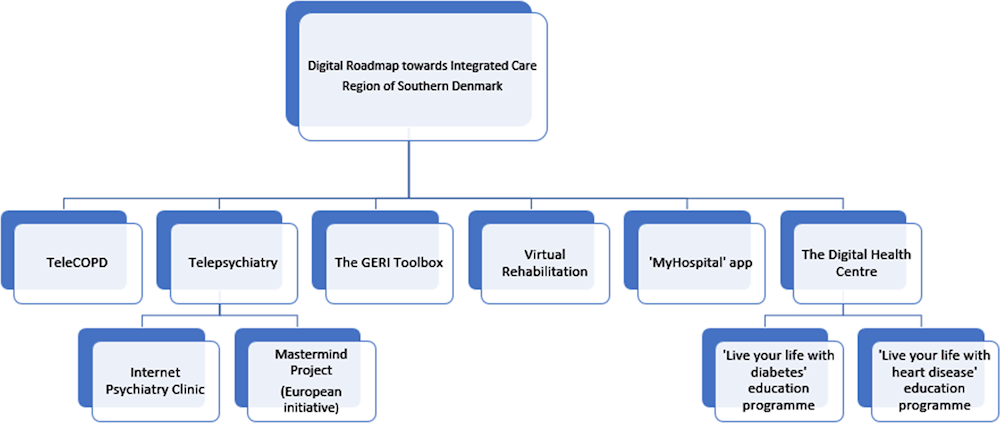

Furthermore, the Digital Roadmap initiative includes six digital interventions or services to improve care for patients with complex diseases (see Figure 10.1 for an infographic of the interventions) (European Commission, n.d.[4]; Region of Southern Denmark, 2021[3]):

TeleCOPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease): provides home‑based virtual consultations from nurses and doctors for patients who experienced an emergency COPD episode and have been discharged from hospital. (Plans to develop a similar programme for patients with heart failure – TeleHeart – are underway.)

TelePsychiatry: The telepsychiatry intervention is run by the Internet Psychiatry Clinic and aims to treat patients with mild to moderate depression and anxiety by providing ready access to telehealth treatment and guidance without a doctor’s referral (Healthcare Denmark, 2018[5]). The service aims to improve access to treatment, increase flexibility for patients and reduce appointment cancellations. The service is run all day, every day and available to those aged 18 years and over who have access to a computer and the internet.

The GERI toolbox (included in the Generic Telemedicine Platform, GTP): the toolbox is a physical “kit” including point-of-care‑testing for basic health exams and digital cross-sectorial communication platform. Using the GERI toolbox, nurses during a home visit undertake tests, with results directly shard via a joint IT-platform to the patient’s home care nurse, general practitioner (GP) and hospital (the results are provided alongside the patient’s medical history). The purpose of sharing information is to identify whether a patient’s health is deteriorating before the point at which it is necessary to admit the patient to hospital. The GERI toolbox also aims to strengthen and simplify communication and collaboration between health sectors (the IT-platform is accessible for community, primary and secondary care physicians and nurses) (Centre for Innovative Medical Technology, n.d.[6]).

Virtual Rehabilitation: an online physical rehabilitation programme, which includes over 600 video exercises tailored to suit patient needs (e.g. patients with COPD, cardiovascular disease (CVD), and musculoskeletal conditions). Lessons provided online are supplementary to in-person physical therapy sessions. Patients can access virtual rehabilitation using a smartphone, tablet or via the web.

The Digital Health Centre: provides online education classes to patients with type 2 diabetes and/or heart conditions on how to lead a healthy lifestyle. For example, by providing tools and support for self-managing changes in diet and levels of physical activity. By switching to an online platform, the Digital Health Centre aims to improve flexibility and therefore participation in education classes.

“My Hospital” app: the My Hospital app, developed at Odense University Hospital in 2014, is a platform for digital communication with patients and clinicians via the use of electronic health records (EHRs). The app helps patients find relevant information about their course of treatment; keep a journal of illness/conditions/symptoms; communicate with the hospital; share data (e.g. on blood pressure, weight, temperature); and view appointments (Centre for Innovative Medical Technology, n.d.[7]). In 2019, the virtual rehabilitation programme was included in My Hospital app. The app is free and available to those with access to a smartphone or the internet. The purpose of the app is encourage patients to become more involved in their own treatment and rehabilitation thereby improving patient empowerment.

Some of the projects included in the Digital Roadmap initiative operate at the region or municipality level, while others operate across the country.

Figure 10.1. Overview of interventions in the Digital Roadmap initiative

OECD Best Practice Framework Assessment

This section analyses the Digital Roadmap initiative against the five criteria within OECD’s Best Practice Identification Framework – Effectiveness, Efficiency, Equity, Evidence‑base and Extent of coverage (see Box 10.1 for a high-level assessment of the project). Further details on the OECD Framework are in Annex A.

Box 10.1. Assessment of the Digital Roadmap initiative

Effectiveness

Data on the overall effectiveness of the Digital Roadmap initiative is not available – for this reason, the section on effectiveness examined data from individual interventions which make up the initiative:

Academic studies of TeleCOPD found the intervention has the potential to reduce hospital readmissions, for example by up to 10%

A study of MasterMind, a type of telepsychiatry intervention, found 29% of participants reported a reduction in depressive symptoms

Patients accessing the Digital Health Centre reported positive feedback on their experience of the available education programs (e.g. usability and the content provided)

A study of GERI Toolbox, a tool to improve home visits delivered by nurses, found both nurses and patients are satisfied

A pilot project involving 300 patients found the virtual rehabilitation intervention found patients are more likely to perform rehabilitation exercises correctly and train more in general, while patients reported a higher quality training experience.

Efficiency

Digital health interventions have the potential to reduce costs while maintaining access to high-quality care

Data on efficiency for specific interventions with the Digital Roadmap initiative is limited to just one intervention – TeleCOPD. TeleCOPD is estimated to lead to a net economic impact of DKK 488 million (EUR 66 million) over a period of five years when targeting patients with severe or very severe COPD. A separate study, which examined the cost-effectiveness of TeleCOPD when provided to all COPD patients, however, found the intervention is above willingness-to-pay thresholds typically applied in Europe.

Equity

An evaluation of interventions within the Digital Roadmap initiative do not break down data by population groups. For this reason, there is no conclusive evidence on what impact the initiative has on reducing health inequalities.

More broadly, digital health interventions have both advantages and disadvantages in terms of reducing inequalities. For example, digital services improve access to those with mobility issues and/or who live in hard-to-reach areas, conversely, less advantaged populations are less likely to use or have access to technology.

Evidence‑base

The quality of evidence support TeleCOPD and Telepsychiatry is robust using data from the Region of Southern Denmark and the broader literature of similar interventions. However, the impact of remaining interventions was assessed primarily using patient surveys, which is low on the hierarchy of evidence.

Extent of coverage

The Digital Roadmap initiative is accessible to all users of healthcare in the Region of Southern Denmark, which covers 1.2 million people.

Data on uptake across the interventions which make up the initiative are not available.

Effectiveness

The section summarises evidence on the effectiveness of individual interventions that make up the Digital Roadmap initiative.

TeleCOPD

Research studies analysing the impact of the TeleCOPD recorded a reduction in hospital admissions and a high levels of patient satisfaction:

Sorknaes et al. (2013[8]): using a randomised controlled trial, the authors assessed the impact of teleconsultations for patients with respiratory diseases or severe COPD. The number of hospital readmissions within 26 weeks of discharge for the intervention group was 1.4 compared to 1.6 in the control group. The difference between the two groups was not statistically significant.

Sorknaes et al. (2010[9]): using an intervention and control group study, the authors assessed the impact of TeleCOPD, also using hospital readmissions as the primary outcome measure. Findings from the analysis show a 10% reduction in the risk of early readmission to hospital among those who received TeleCOPD. TeleCOPD was also associated with higher levels of patient and nurse satisfaction.

An evaluation of a similar pilot project implemented in the Region of Northern Denmark – TeleCare North – also found positive results. Specifically, the pilot (Healthcare Denmark, 2021[10]):

Reduced the number and length of hospitalisations for COPD patients by 11% and 20%, respectively.

Improved patients control over their diseases and increased awareness of their symptoms.

Nearly three‑quarters of COPD patients (71.7%) felt an increase sense of safety from telemonitoring, half of all patients stated that experienced an increased awareness of COPD symptoms and responded proactively, and finally, nearly all patients (96%) found the system easy to use (Oliveira Hashiguchi, 2020[11]).

Due to the promising results of these two pilot projects (in the Regions of Southern Denmark and also Northern Denmark), the Danish Government and the Danish Regions agreed to implement telemedicine home monitoring for COPD patients across the whole country (PA Consulting Group, 2017).

Telepsychiatry

Between 2013 and 2015, the Region of Southern Denmark ran a pilot Telepsychiatry intervention. A report analysing the impact of the pilot could not conclude whether teleconsultation therapy sessions for patients with depression had the same impact as usual therapy (Rasmussen, Wentzer and Fredslund, 2016[12]).

Another telepsychiatry intervention run in the Region of Southern Denmark is Mastermind (Management of mental health through advanced technology and services – telehealth for the MIND). Mastermind is a European project that implemented iCBT (internet-based cognitive therapy) for almost 5 000 adults with depression (MasterMind, 2021[13]). This intervention collected data on clinical symptoms of patients (“no symptoms”, “mild”, “moderate”, “severe”, and “very severe”), before and after treatment. The final evaluation report of the project showed that 29% of patients reported they experienced a reduction in depressive symptoms (Pedersen et al., 2017[14]).

The Digital Health Centre

The Digital Health Centre developed the Digital Patient Education consists of two patient education programs called “Live your life with diabetes” and “Live your life with heart disease”. Both programs offer patients consultations with healthcare professionals, e‑learning modules and online group sessions such as webinars (Det Digitale Sundhedscenter, 2021[15]; Health Innovation Center of Southern Denmark, 2021[16]).

Participants of the Digital Patient Education programme provided positive feedback of their experience in the pilot project. A report analysing the impact of the pilot project, which included 149 citizens (97 with type 2 diabetes and 52 with heart disease), found 80% of patients were satisfied with the programme and experienced positive effects from using digital education. Further, participants gave positive feedback on both the e‑learning platform (e.g. “easy and understandable”) and on the webinars (e.g. content and pedagogy) (Det Digitale Sundhedscenter, 2018[17]).

The Digital Health Centre fulfils its objective to improve patients’ health habits. Patients stated the programme had positive effects on their health habits – after participating in the diabetes course, around one‑third of the participants have had their eyesight and feet checked by a health professional (Det Digitale Sundhedscenter, 2018[17]).

GERI toolbox

An 18‑month observational study of the GERI Toolbox found (Andersen-Ranberg et al., 2020[18]):

Nurses felt that were supported during the decision-making process

Two-third of general practitioners felt that Toolbox reduced acute hospital admissions (specific data, however, is not available)

Patients felt safe with the acute nurses utilising the Toolbox

Approximately half of all patients felt the service was equivalent to a GP house call.

Virtual rehabilitation

The main objective of this virtual platform is to strengthen the quality of the integrated rehabilitation process by sharing patient data, increasing support during the patients’ rehabilitation journey and improving collaboration across sectors.

A pilot project in 2012 involving over 300 patients assessed the impact of the Virtual Rehabilitation – key findings are summarised below (Nissen, 2012[19]):

Therapists report that patients are more likely to perform rehabilitation exercises correctly and train more in general when using the virtual platform compared to exercises handed out on paper.

The virtual rehabilitation is shown to be just as accessible for patients as paper-based exercises

Virtual rehabilitation helps patients maintain their training (e.g. SMS reminders)

Patients reported receive a higher quality training experience virtually than when compared to exercises provided on paper.

MyHospital app

Similar to the GERI toolbox, to date there is limited evidence measuring the impact of the MyHospital App. However, research studies have relied on the app to collect patient data, such as patient-reported outcome measures. For example, Møller et al. (2021[20]) in their evaluation of a new cancer treatment, uploaded a survey to the My Hospital app in order to collect data on patient-reported outcome measures.

Efficiency

Digital health interventions have the potential to reduce costs while continuing to provide patients with the same or an even better level of care. For example, digital health interventions, reduce patient travel and waiting time (thereby improving productivity), shorten the length of consultations thereby increasing the volume of consultations, and also have lower unit cost when compared to face‑to-face services.

Similar to “Effectiveness”, results for efficiency are summarised according to individual interventions within Digital Roadmaps. Results are not available for the Region of Southern Denmark; therefore, the analysis relies on data from the same intervention implemented in a different region or country.

Results for efficiency are limited to just two interventions operating under Digital Roadmaps – TeleCOPD and Telepsychiatry. Results from analysis show mixed, inconclusive results.

TeleCOPD

Provided below are results for the two most recent efficiency analyses of TeleCOPD. At a high-level, TeleCOPD is only cost-effective when targeting patients with severe or every severe COPD:

Witt Udsen et al. (2017[21]) conducted a cost-utility analysis of TeleCOPD as it operates in the Northern Region of Denmark. Results from study estimate TeleCOPD has a cost per quality-adjusted life year (QALY) of EUR 55 327, which, on average, is above willingness-to-pay thresholds in countries across Europe and the United Kingdom (around EUR 50 000 according to (Vallejo-Torres et al., 2016[22])). This result indicates TeleCOPD is unlikely to be cost-effective when provided to all COPD patients. TeleCOPD, however, was cost effective under more favourable sensitivity analyses, for example:

when procurement prices of technologies drop due to wider coverage (cost per QALY = EUR 46 931)

when reducing the average per patient monitoring time, which also reduced costs (cost per QALY = EUR 39 854).

The PA Consulting Group in (2017[23]) undertook a business case analysis of scaling-up TeleCOPD across the whole of Denmark. Assuming the intervention targets those with either severe or very severe COPD (Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) grades 3 or 4), it is estimated to have an accumulative net economic impact of DKK 483 million (EUR 66 million) over a period of five years. To take into account uncertainty, the authors also presented figures for a worse and best case scenario – i.e. DKK 388 million and DKK 578 million (EUR 52‑78 million), respectively.

Telepsychiatry

Data on efficiency for telepsychiatry is not available; however, there is information on the costs of operating the intervention. See Box 10.2 for further details.

Mastermind, a separate telepsychiatry intervention, did report findings from an economic evaluation – however, results are not specific to the Region of Southern Denmark, instead they represent several regions in Spain and Italy, as well as Scotland, the Netherlands and Germany. Specifically, a European Commission funded study found the cost of reducing depression by one measurement level varies widely from EUR 165 to EUR 1917 across countries. The differences in estimates may be due to different structures and cost models, the volume of treatment, and/or how well established daily operation activities are (European Commission, 2017[24]). The study did not indicate whether these figures fall under a pre‑specified willingness-to-pay threshold.

Box 10.2. Costs of implementing and operating telepsychiatry

An evaluation of the pilot telepsychiatry project analysed the two‑year operating phase of the intervention and estimated that costs per patient in telemediated psychiatric treatment were probably lower than the average total cost of treatment courses. However, this excludes development costs of the project (such as “shift management” costs and a feasibility study of patients not receiving treatment). If all development costs are included, the estimated cost per patient is around DKK 5 million (EUR 670 000) for around 680 patients included in annual treatment (for nationwide distribution), which would equal DKK 7 353 (EUR 990) per patient, per year (Rasmussen, Wentzer and Fredslund, 2016[12]).

The same report by Rasmussen et al. (2016[12]) also notes that the average costs per treated patient is DKK 9 780 (EUR 1 300). However, a considerable proportion of this cost is spent on recruiting patients. If these costs are excluded, the expected average for telepsychiatry treatment is lower at DKK 6 780 (EUR 900) per patient. Comparatively, expected public health insurance costs for usual course of treatment is DKK 4 820 (EUR 650).

Equity

Studies measuring the effectiveness and efficiency of Digital Roadmap interventions did not report results across population groups. Therefore, it was not possible to assess what impact Digital Roadmaps has on reducing health inequalities. The section on equity therefore summarises, at a high level, the impact of digital health intervention on equality (see Box 10.3).

Box 10.3. Digital health interventions and equality

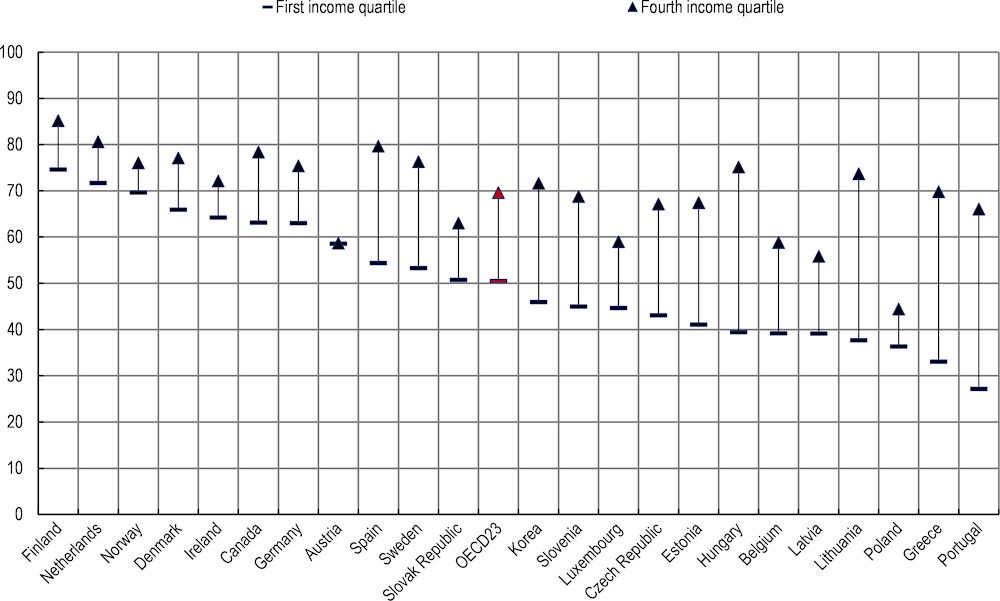

Telehealth and digital communication can have both advantages and disadvantages in terms of accessing priority groups. While telemedicine can allow patients with mobility issues or those from remote areas to access treatment, others may have difficulties using and/or accessing the technology (digital exclusion). For example, digital health interventions are more popular among younger, higher- educated populations: research undertaken by OECD estimated adults in the highest income quartile are markedly more likely to use the internet to research health information, compared to adults in the lowest income quartile (see Figure 10.2). Other groups less likely to use digital health interventions include older populations and those living in rural areas due to factors such as cost, lower digital health literacy skills and limited broadband access (Bol, Helberger and Weert, 2018[25]; Azzopardi-Muscat and Sørensen, 2019[26]; Oliveira Hashiguchi, 2020[11]).

Figure 10.2. Per cent using internet to seek health information by income quartile

Note: Data are shown for 2020 and refer to internet searches in the last three months.

Source: OECD database on ICT Access and Usage by Households and Individuals.

Evidence‑base

The evidence‑base criteria assesses the quality of evidence used to measure the impact of interventions within the Digital Roadmaps initiative, as outlined under preceding best practice criteria. The Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies from the Effective Public Health Practice Project is a commonly used tool to assess the quality of evidence, with a particular focus on academic articles. Only two articles measuring the impact of Digital Roadmap interventions are eligible for this assessment – both papers by Sorknaes et al. (2013[8]) and (2010[9]), which measured the effectiveness of TeleCOPD (see Table 10.1). However, only the (2010[9]) paper was assessed given the paper form (2013[8]) is not publicly available. The quality of evidence for remaining studies relied on a qualitative assessment, as outlined in Box 10.4.

Table 10.1. Evidence‑based assessment – the Digital Roadmap initiative

|

Assessment category |

Question |

Score Sorknaes et al. (2010[9]) |

|---|---|---|

|

Selection bias |

Are the individuals selected to participate in the study likely to be representative of the target population? |

Somewhat likely |

|

What percentage of selected individuals agreed to participate? |

98% |

|

|

Selection bias score: |

Moderate |

|

|

Study design |

Indicate the study design |

Observational study (cohort analytic, two group pre and post) |

|

Was the study described as randomised? |

No |

|

|

Was the method of randomisation described? |

N/A |

|

|

Was the method of randomisation appropriate? |

N/A |

|

|

Study design score: |

Moderate |

|

|

Confounders |

Were there important differences between groups prior to the intervention? |

No |

|

What percentage of potential confounders were controlled for? |

Some (60‑79%) |

|

|

Confounders score: |

Moderate |

|

|

Blinding |

Was the outcome assessor aware of the intervention or exposure status of participants? |

Yes |

|

Were the study participants aware of the research question? |

Yes |

|

|

Blinding score: |

Weak |

|

|

Data collection methods |

Were data collection tools shown to be valid? |

Yes |

|

Were data collection tools shown to be reliable? |

Yes |

|

|

Data collection methods score: |

Strong |

|

|

Withdrawals and dropouts |

Were withdrawals and dropouts reported in terms of numbers and/or reasons per group? |

Yes |

|

Indicate the percentage of participants who completed the study? |

99% |

|

|

Withdrawals and dropouts score: |

Strong |

Source: Effective Public Health Practice Project (1998[27]), “Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies”, https://www.nccmt.ca/knowledge-repositories/search/14.

Box 10.4. Quality of evidence supporting the Digital Roadmap initiative

This box summarises the quality of evidence use to measure the impact of interventions within the Digital Roadmap initiative.

TeleCOPD

In addition to the quality of evidence assessment outlined in Table 10.1, this section provides an overview of the evidence supporting telemonitoring schemes for COPD patients more broadly.

Hong and Lee (2019[28]) conducted a systematic review and meta‑analysis to analyse the effect of telemonitoring on COPD patients using information from 27 randomised controlled trials (RCTs). They used Cochrane risk of bias (RoB) for RCTs and assessed selection bias, allocation bias, performance and detection bias, attrition bias and reporting bias by scoring low, high and unclear risk. Four studies had a high risk of selection bias, and almost all studies reported an unclear allocation concealment. Only two studies reported blindness. Indeed, the blinding of participants was lacking, but treatment for participants cannot be blinded because of intervention characteristics.

Cruz et al. (2014[29]) undertook a systematic review to assess the effectiveness of home telemonitoring in patients with COPD. In total, 10 articles (9 studies) met the inclusion criteria, of which: eight were RCTs (two high quality, five good quality and one fair to good quality); one was an experimental study with a control group (good quality), and one was quasi‑experimental with a control group (good quality).

Although telemonitoring for patients with heart disease is not currently part of the Digital Roadmap initiative, the quality of evidence supporting such interventions is included given plans to introduce TeleHeart – telemonitoring for patients with heart disease.

Yun et al. (2018[30]) performed a systematic review and meta‑analysis to evaluate the effectiveness of telemonitoring in the management of patients with heart failure. The quality of the 37 selected RCTs was assessed by the Cochrane RoB tool. More than 25% of the studies had a high risk of bias for reporting bias. The risk of device support was designated “uncertain” in the majority of the studies. Because most of the included studies reported objective outcomes, such as death or hospitalisation, the overall risk of detection bias was low.

Telepsychiatry

The evaluation of MasterMind, a telepsychiatry intervention, relied on survey data from patients both before and after accessing the intervention. Further details on the methodology used – such as the number of patients, selection criteria, questionnaire use – are not available (Pedersen et al., 2017[14]). Therefore, the evidence supporting telepsychiatry is supported in this setting by a review of the broader literature.

Guiana et al. (2020[31]) undertook a systematic review to evaluate the impact of telepsychiatry on depression. The systematic review included 14 studies all of which were RCTs, which is the most robust method for establishing causality. The review concluded satisfaction with telepsychiatry is equivalent or higher than face‑to-face care, relieves depressive symptoms and is cost-effective in the long run.

Remaining interventions

The evidence supporting remaining interventions – Digital Health Centre, GERI Toolbox and Virtual rehabilitation – relied on survey feedback from participants to assess performance. Surveys measuring patient experiences are considered “low-quality” evidence.

Extent of coverage

The Digital Roadmaps initiative targets all users of healthcare in the Region of Southern Denmark, which has a population of 1.2 million (Region Syddanmark, 2021[32]). Interventions within Digital Roadmaps often however target specific populations – e.g. TeleCOPD focuses on those diagnosed with the disease. Data on the extent of coverage for individual interventions is very limited, with information only available for the My Hospital app and Telepsychiatry:

My Hospital app: since its inception in 2014, the app has been accessed by 30 000 patients

Telepsychiatry: in its first year, nearly 500 patients accessed mental health services online with this figure growing to over 1 800 by 2017 (Healthcare Denmark, 2018[5]).

Policy options to enhance performance

Policy options available to policy makers (e.g. region / state / national governments) and administrators of the Digital Roadmap initiative are outlined in this section and refer to each of the five best practice criteria.

Enhancing effectiveness

Continue to build levels of digital literacy among patients with a focus on disadvantaged population groups. Relative to other OECD and EU27 countries, Denmark has a digitally advanced healthcare system. As a result, a high proportion of people in the country (72%) use the internet to seek health information (OECD, 2019[33]). The proportion of patients seeking care online, however, differs across populations with lower levels recorded for lower socio-economic groups (in terms of income and educational attainment) as well as the older population. Therefore, any policy efforts to promote digital health literacy (HL) should focus on groups who face barriers to accessing and utilising telehealth, given such groups often stand to benefit most.

Digital HL is also high among health professionals in Denmark but can always be improved. Indicators measuring digital HL levels in Denmark suggest relative to other countries, the workforce feel confident using digital tools as part of routine practice. For example, out of all European countries with available data, Denmark recorded the highest eHealth adoption score among general practitioners (GPs) (a composite index score which brings together data on adoption of electronic health records, telehealth, personal health records and health information exchange). Nevertheless, it is important to continue improving digital HL skills among health professionals so that they have the skills and confidence to safely and effectively adopt digital work tools. For example, by developing digital health competency frameworks that inform what changes to the education of health professionals are needed, with a particular focus on physicians, as well as developing concrete guidelines on how to integrate digital health topics into education and training programs.

Enhancing efficiency

Prioritise economic evaluations of interventions within the Digital Roadmap initiative. As outlined under “Efficiency”, there is limited evidence supporting the efficiency of specific interventions within the Digital Roadmap initiatives. This findings aligns with the broader literature and is one of the key barriers to the wider use of telehealth/telemedicine (Oliveira Hashiguchi, 2020[11]). Economic evaluations should therefore be prioritised, such as cost-benefit, cost-minimisation and cost-effectiveness analyses. Regardless of the method chosen, it is important that researchers take a broad perspective as opposed to a health system/government perspective. Specifically, by taking into account cost categories from the patient perspective including patient travel and waiting time, both of which result in loss productivity, as well as a reduction in downstream utilisation of healthcare services. For example, research undertaken in Canada found the Canadian Ontario Telemedicine Network reduced patient travel distance by 270 million km in one year, leading to costs savings from a reduction in travel grants by CAD 71.9 million (EUR 50.2 million) (OTN, 2018[34]). Failing to account for such costs risks excluding key variables that make a more favourable case for telehealth/telemedicine, which limits the possibility of scaling up and transferring such interventions.

Enhancing equity

Policies to increase access and utilisation of Digital Roadmap interventions among priority population groups can reduce health inequalities. There are groups in the population who are less likely to utilise and therefore benefit from digital health products – e.g. the older population are less likely to be digitally health literate, while economically disadvantaged groups may not have regular access to the internet (Bol, Helberger and Weert, 2018[25]; Azzopardi-Muscat and Sørensen, 2019[26]; Oliveira Hashiguchi, 2020[11]). Governments and other relevant policy makers can respond by focusing efforts to build HL and digital HL on priority population groups (e.g. through targeted training programs). More direct action that can be implemented by Digital Roadmap administrators include:

Targeted promotion campaigns as well as the provision of detailed, tailored, advice on how to use the interventions within the initiative

Collecting data that can be disaggregated by priority population groups (e.g. information on level of education as a proxy for SES status). This information can subsequently be used to amend interventions to better to suit the needs of priority populations.

Failing to address the needs of priority population groups risks widening existing health inequalities.

Enhancing the evidence base

Collect additional indicators to the measure the impact of interventions on patient health outcomes. As outlined under “Evidence‑base”, the quality of evidence supporting interventions within the Digital Roadmap initiative are mixed – i.e. telemonitoring programs, such as TeleCOPD, are supporting by rigorous academic studies, while the remaining interventions rely on qualitative feedback from patients and providers. For interventions supported by low-quality evidence – Digital Health Centre, GERI Toolbox and Virtual rehabilitation – administrators from the Digital Roadmap initiative should also focus on collecting robust forms of data to evaluate impact. See Box 10.5 for a list of example indicators. Although patient/provider experiences are low quality in the hierarchy of evidence, they are an important source of information and should continue to be collected. In particular, validated forms of self-reported feedback such as the EQ‑5D, which measures quality of life.

A stronger evidence‑base will ultimately increase trust among both patients and providers thereby increasing uptake across the population.

Box 10.5. Example indicators to measure impact of Digital Roadmap interventions

This box outlines indicators useful for measuring the impact of interventions within the Digital Roadmap initiative. The indicators should complement rather than replace indicators measuring patient and provider experiences. Evaluation methodologies that collect indicators for a control and intervention group are the most robust, in particular where allocation into either group is random. The list of indicators is not exhaustive.

Digital Health Centre: Live your life with diabetes / Live your life with heart disease

Levels of physical activity (e.g. steps per day, minutes per day or moderate to vigorous exercise)

Fruit and vegetable consumption

Weight or body mass index (BMI)

Diabetes specific: Type 2 diabetes incidence, A1C, LDL cholesterol, or microalbuminuria

GERI Toolbox

Number of hospital admissions

Virtual rehabilitation

Short Physical Performance Battery

Quality of life measurement (e.g. EQ‑5D)

Anxiety/depression levels

For COPD patients: minute ventilation, exercise capacity, max VO2 (measures oxygen uptake), dyspnea (i.e. shortness of breath)

Researchers evaluating individual programs within Digital Roadmaps should be aware of the potential overlap between interventions. This overlap makes it difficult to ascertain the impact of each separate intervention.

Continue to build evidence supporting the efficiency of digital health interventions. For further details, see “Enhancing efficiency”

Enhancing extent of coverage

Encourage health professionals to promote interventions within the Digital Roadmap initiative. There are high-levels of public trust in the health workforce; therefore, health professionals can play an important role in boosting uptake of interventions within the Digital Roadmap initiative. A way of encouraging adoption of digital tools is to make them available in provider settings and have “professionals demonstrate and support their use” (OECD, 2019[35]).

Ensure interventions within the Digital Roadmap are both trusted and non-burdensome for health professionals. Health professionals whose experience with digital health interventions is burdensome are less likely to use as well as promote such interventions. For this reason, administrators of the Digital Roadmap initiative should ensure that any new interventions or updates to existing interventions (OECD, 2019[35]):

Are evidence‑based in order to maintain trust among health professionals and patients

Include input and feedback from health professionals and patients, who are the end-users

Do not negatively affect usability and continue to be integrated into current practice (i.e. do not increase the workload of health professionals).

Continue to build the evidence base supporting interventions within the Digital Roadmap initiative. Uptake of interventions within the Digital Roadmap initiative is likely to grow with the level of available evidence supporting its effectiveness and efficiency. See “Enhancing the evidence base” for further details.

Transferability

This section explores the transferability of the Digital Roadmap initiative and is broken into three components: 1) an examination of previous transfers; 2) a transferability assessment using publicly available data; and 3) additional considerations for policy makers interested in transferring this intervention.

Previous transfers

The Digital Roadmap initiative is one of four “good practices” within the European Commission’s Joint Action on implementation of digitally enabled integrated person-centred care (JADECARE). As part of JADECARE, nine Member States in Europe will adopt the Digital Roadmap initiative over the period 2020‑23. Next adopters participated in a study visit where the owners of the intervention in Denmark presented the transferability of individual interventions that make up the initiative.

Many of the interventions within the Region of Southern Denmark’s Digital Roadmap initiative operate across the whole country demonstrating their transferability potential. For example, TeleCOPD and Telepsychiatry are available to all COPD patients in Denmark.

Transferability assessment

The following section outlines the methodological framework to assess transferability and results from the assessment.

Methodological framework

Details on the methodological framework to assess transferability can be found in Annex A.

Several indicators to assess the transferability of the Digital Roadmap initiative were identified (see Table 10.1). Indicators were drawn from international databases and surveys to maximise coverage across OECD and non-OECD European countries. Please note, the assessment is intentionally high level given the availability of public data covering OECD and non-OECD European countries.

Table 10.2. Indicators to assess transferability – the Digital Roadmap initiative

|

Indicator |

Reasoning |

Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

|

Population context |

||

|

ICT Development Index* |

Digital Roadmap (DR) interventions are more transferable to countries that are digitally advanced |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Individuals using the Internet for seeking health information – last 3 m (%) |

DR interventions more transferable to a population comfortable seeking health information online |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Sector context (digital health sector) |

||

|

eHealth composite index of adoption score amongst GPs in Europe** |

DR interventions are more transferable to countries where GPs are comfortable using eHealth technologies |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

% of tertiary institutions (public and private) that offer ICT for health (eHealth) courses |

DR interventions are more transferable if health professional students receive eHealth training |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

% of institutions or associations offering in-service training in the use of ICT for health as part of the continuing education of health professionals |

DR interventions are more transferable if health professionals have appropriate eHealth training |

🡹 value = more transferable |

|

Political context |

||

|

A national eHealth policy or strategy exists |

DR interventions are more transferable if the government is supportive of eHealth |

‘Yes’ = more transferable |

|

A dedicated national telehealth policy or strategy exists |

DR interventions are more transferable if the government is supportive of telehealth |

‘Yes’ = more transferable |

|

Economic context |

||

|

Special funding is allocated for the implementation of the national eHealth policy or strategy |

DR interventions are more transferable if there already is allocated funding for eHealth |

‘Yes’ = more transferable |

|

% of funding contribution for eHealth programmes provided by public funding sources over the previous two years |

DR interventions are more transferable if eHealth programme funding mostly comes from public sources |

High proportion = more transferable |

Note: *The ICT development index represents a country’s information and communication technology capability. It is a composite indicator reflecting ICT readiness, intensity and impact (ITU, 2020[36]). **The eHealth composite index of adoption amongst GPs is made up of adoption in regards to electronic health records, telehealth, personal health records and health information exchange.

Source: ITU (2020[36]), “The ICT Development Index (IDI): conceptual framework and methodology”, https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/mis/methodology.aspx; OECD (2019[33]), “Individuals using the Internet for seeking health information – last 3 m (%) (all individuals aged 16‑74)”; European Commission (2018[37]), “Benchmarking Deployment of eHealth among General Practitioners (2018)”, https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/d1286ce7-5c05-11e9-9c52-01aa75ed71a1; WHO (2015[38]), “Atlas of eHealth country profiles: The use of eHealth in support of universal health coverage”, https://www.afro.who.int/publications/atlas-ehealth-country-profiles-use-ehealth-support-universal-health-coverage.

Results

Table 10.3 outlines results from the transferability assessment using indicators in Table 10.2. Overall, Denmark has a relatively advanced digital health system and is therefore well placed to offer interventions deliver interventions part of the Digital Roadmap initiative. Countries with less advanced digital health systems may experience transfer and implementation barriers. Specific details from the assessment are below:

Access to and use of digital healthcare is high in Denmark when compared to other OECD and EU27 countries. For example, nearly 70% of people in Denmark use the internet to access healthcare compared to just over 50% among all OECD/EU countries. Further, alongside Korea, Denmark has the highest ICT development index, a composite indicator measuring IT access, use and skills at the country level.

Available indicators also suggest the health workforce in Denmark are digitally health literate. For example, a “very high” proportion of institution offer health professionals ICT training as part of their continual education requirements. For the majority of remaining countries (64% of those with available data), ICT training for health professionals is only offered in a “medium” or “low” proportion of institutions.

There is strong political support accompanied by relatively high levels of funding for eHealth programs in Denmark. Denmark has both an eHealth and telehealth policy to support programs such as the Digital Roadmap initiative. While most examined countries also have an eHealth policy (73% of those with available data), far fewer also have a telehealth policy (25%). Regarding funding, specific funds are available to implement Denmark’s eHealth policy. Further, a “very high” proportion of eHealth funding comes from the Danish Government, indicating the government has a keen interest in pursuing digital health initiatives. While the government is in general the main contributor to eHealth funding among examined countries, this is not always the case – e.g. in a fifth of all countries, the proportion of eHealth spending from government is “low”.

Table 10.3. Transferability assessment by country (OECD and non-OECD European countries) – the Digital Roadmap initiative

A darker shade indicates the Digital Roadmap initiative may be more transferable to that particular country

|

Country |

ICT Development Index (2015) |

Individuals using the Internet for seeking health information – last 3 m (%) |

eHealth composite index of adoption score amongst GPs in Europe |

% of tertiary institutions (public and private) that offer ICT for health (eHealth) courses |

Proportion of institutions or associations offering in-service training in the use of ICT for health as part of the continuing education of health professionals |

A national eHealth policy or strategy exists |

A dedicated national telehealth policy or strategy exists |

Special funding is allocated for the implementation of the national eHealth policy or strategy |

% funding contribution for eHealth programmes provided by public funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Denmark |

8.80 |

67.36 |

2.86 |

Medium |

Very high |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Australia |

8.20 |

42.46 |

n/a |

Medium |

High |

Yes |

No |

n/a |

Very high |

|

Austria |

7.50 |

53.24 |

1.91 |

Low |

Low |

No |

No |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Belgium |

7.70 |

48.74 |

2.07 |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

Combined* |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Bulgaria |

6.40 |

34.00 |

1.81 |

Medium |

Medium |

Yes |

Combined |

Yes |

Low |

|

Canada |

7.60 |

58.70 |

n/a |

High |

Low |

Yes |

No |

n/a |

Very high |

|

Chile |

6.10 |

27.48 |

n/a |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

No |

n/a |

Very high |

|

Colombia |

5.00 |

41.47 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Costa Rica |

6.30 |

58.00 |

1.93 |

Medium |

Low |

Yes |

No |

No |

Very high |

|

Croatia |

6.80 |

53.00 |

2.18 |

Low |

Medium |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Cyprus |

6.30 |

58.00 |

1.93 |

Medium |

Low |

Yes |

Combined |

No |

Very high |

|

Czech Republic |

7.20 |

56.46 |

2.06 |

Medium |

No |

Combined |

No |

Low |

|

|

Estonia |

8.00 |

59.54 |

2.79 |

Medium |

Low |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Finland |

8.10 |

76.32 |

2.64 |

Medium |

Medium |

Yes |

Combined |

Yes |

Very high |

|

France |

8.00 |

49.59 |

2.05 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes, but not national |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Germany |

8.10 |

66.49 |

1.94 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Greece |

6.90 |

49.86 |

1.79 |

Medium |

Medium |

Yes |

Combined |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Hungary |

6.60 |

60.46 |

2.03 |

Low |

n/a |

No |

No |

No |

Very high |

|

Iceland |

8.70 |

64.68 |

n/a |

Very high |

Very high |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Ireland |

7.70 |

56.87 |

2.10 |

n/a |

Low |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Low |

|

Israel |

7.30 |

50.00 |

n/a |

High |

Low |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Italy |

6.90 |

35.00 |

2.19 |

Low |

High |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Japan |

8.30 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

No |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Korea |

8.80 |

50.38 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Latvia |

6.90 |

47.89 |

1.83 |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

Combined |

Yes |

Low |

|

Lithuania |

7.00 |

60.63 |

1.65 |

Medium |

Low |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

High |

|

Luxembourg |

8.30 |

58.17 |

1.78 |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

Combined |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Malta |

7.50 |

59.00 |

n/a |

Very high |

Very high |

No |

No |

No |

Very high |

|

Mexico |

4.50 |

49.76 |

n/a |

Medium |

Low |

No |

No |

n/a |

High |

|

Netherlands |

8.40 |

73.97 |

n/a |

High |

High |

Yes |

Combined |

Yes |

Very high |

|

New Zealand |

8.10 |

n/a |

n/a |

Medium |

Very high |

Yes |

No |

Low |

|

|

Norway |

8.40 |

68.98 |

n/a |

Low |

Medium |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Poland |

6.60 |

47.40 |

1.84 |

High |

Medium |

Yes |

Combined |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Portugal |

6.60 |

49.41 |

2.12 |

Low |

Low |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

High |

|

Romania |

5.90 |

33.00 |

1.79 |

n/a |

n/a |

Yes |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Slovak Republic |

6.70 |

52.64 |

1.76 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

|

Slovenia |

7.10 |

48.07 |

2.00 |

High |

High |

No |

No |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Spain |

7.50 |

60.13 |

2.37 |

Low |

Medium |

No |

No |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Sweden |

8.50 |

62.24 |

2.52 |

Very high |

Very high |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Very high |

|

Switzerland |

8.50 |

66.87 |

n/a |

Low |

Very high |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

Low |

|

Türkiye |

5.50 |

51.26 |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

No |

Combined |

Yes |

Low |

|

United Kingdom |

8.50 |

66.89 |

2.52 |

Medium |

High |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Very high |

|

United States |

8.10 |

38.33 |

n/a |

Low |

Low |

Yes |

No |

n/a |

n/a |

Note: n/a = data is missing. *Combined with eHealth policy or strategy.

Source: See Table 10.2.

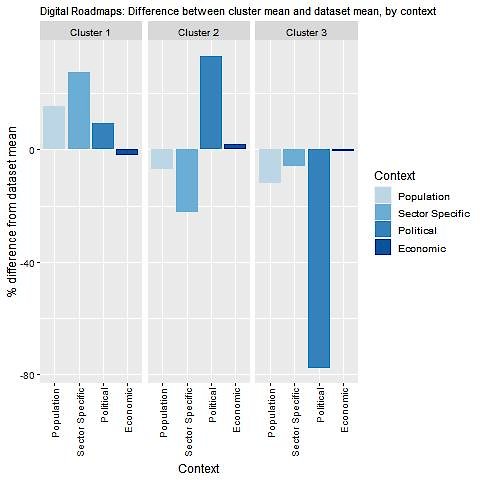

To help consolidate findings from the transferability assessment above, countries have been clustered into one of three groups, based on indicators reported in Table 10.2. Countries in clusters with more positive values have the greatest transfer potential. For further details on the methodological approach used, please refer to Annex A.

Key findings from each of the clusters are below with further details in Figure 10.3 and Table 10.4:

Countries in cluster one have population, political and sector specific arrangements in place to transfer the Digital Roadmaps initiative, and are therefore good transfer candidates. This cluster includes Denmark, the owner country for this intervention.

Countries in cluster two have political priorities, which align with the Digital Roadmap initiative, such as a dedicated national eHealth policy. However, further analysis is needed to ensure these countries have a population and a digital health sector ready to maximise the potential of interventions within the Digital Roadmap initiative.

Countries in cluster three require further analysis to ensure the right conditions are in place to transfer the Digital Roadmap initiatives, in particular, to ensure the initiative aligns with overarching political priorities.

Figure 10.3. Transferability assessment using clustering – the Digital Roadmap initiative

Note: Bar charts show percentage difference between cluster mean and dataset mean, for each indicator.

Source: See Table 10.2.

Table 10.4. Countries by cluster – the Digital Roadmap initiative

|

Cluster 1 |

Cluster 2 |

Cluster 3 |

|---|---|---|

|

Australia Canada Chile Denmark Estonia Iceland Ireland Lithuania New Zealand Sweden Switzerland United Kingdom United States |

Belgium Bulgaria Costa Rica Croatia Cyprus Czech Republic Finland Greece Italy Latvia Luxembourg Netherlands Norway Poland Türkiye |

Austria Hungary Israel Malta Mexico Portugal Slovenia Spain |

Note: Due to high levels of missing data, the following countries were omitted from the analysis: Colombia, France, Germany, Japan, Korea, Romania and the Slovak Republic.

New indicators to assess transferability

Data from publicly available datasets is not sufficiently comprehensive to assess the transferability of the Digital Roadmap initiative. Therefore, Box 10.6 outlines several new indicators policy makers should consider before transferring this intervention. In particular, countries should assess whether current technological infrastructure systems support sharing of patient data and therefore digital integrated care interventions.

Box 10.6. New indicators, or factors, to consider when assessing transferability – the Digital Roadmap initiative

In addition to the indicators within the transferability assessment, policy makers are encouraged the possibility of collecting data for the following indicators:

Population context

How acceptable are digital health interventions among the public?

Do patients have the skills to access healthcare online?

What proportion of the population has access to a smartphone/laptop/compute and the internet?

Does the population trust their personal health information will be used, stored and managed appropriately?

Sector specific context (digital health system)

Are there organisational agreements in place to support the implementation of interventions within the Digital Roadmap initiative?

Are there clear reimbursement mechanisms for telemedicine services?

Is there a common health data infrastructure in place to support Digital Roadmap initiative?

Do regulations support the delivery of healthcare via digital means (i.e. telemedicine)?

Are health professionals supportive of delivering care remotely?

Is there a culture of change and adoption of new technologies among the health workforce?

What, if any, compatible or competing interventions exist?

Political context

Has the intervention received political support from key decision-makers?

Has the intervention received commitment from key decision-makers?

Economic context

Are there additional cost of implementing interventions part of the Digital Roadmap initiative? (e.g. updating technology, creating a harmonious data health infrastructure system)

Conclusion and next steps

In 2020, the Region of Southern Denmark launched the Digital Roadmap towards an Integrated Healthcare Sector (i.e. the Digital Roadmap initiative). The initiative aims to improve co‑ordination across healthcare settings and therefore care for patients, with a specific focus on those living with one or multiple chronic conditions. A number of digital health interventions make up the initiative including TeleCOPD and Telepsychiatry.

The Digital Roadmap initiative has a positive impact on patient experiences, and to a lesser extent, health outcomes. Data on the overall effectiveness of the Digital Roadmap initiative is not available – for this reason, the case study explored the individual performance of each intervention. Evidence from TeleCOPD and Telepsychiatry were the strongest by showing improvements in health outcomes – for example, TeleCOPD can reduce hospital readmissions by up to 10%. The remaining interventions also had a positive impact based on patient experiences, which were measured using patient survey data.

Policy makers should consider recommendations in this case study to improve the overall performance of the Digital Roadmap initiative. Available options to policy makers include continuing to build digital health literacy among providers as well as patients, with a specific focus on disadvantaged population groups – e.g. lower socio-economic status. Disadvantaged groups typically have lower levels of digital health literacy despite having the most to gain from digital interventions. Further, given the paucity of data supporting the efficiency of digital health interventions, future studies should focus on economic evaluations from the perspective of society, as opposed to the government/health system perspective.

Digital health interventions within the Digital Roadmap initiative exist in countries across the OECD/EU, nevertheless, the potential for transfer is greatest among those that are digitally advanced. Telemonitoring interventions for patients with COPD or depressive symptoms are common among OECD and EU countries, indicating interventions within the Digital Roadmap initiative are highly transferable. However, in general, digital health interventions have the greatest transfer potential to countries with digitally advanced healthcare systems.

Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies regarding the Digital Roadmap initiative are summarised in Box 10.7.

Box 10.7. Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies – the Digital Roadmap initiative

Next steps for policy makers and funding agencies to enhance the Digital Roadmap initiative are listed below:

Consider policy options in this report such as:

Ensuring that interventions addresses digital inclusion, to reduce rather than exacerbate health inequalities

Evaluating the economic potential of digital health interventions based on the perspective of society – i.e. by including changes to waiting and travelling times, workload of healthcare workers, and higher work productivity of patients

Report on findings from the experiences of countries transferring the Digital Roadmap initiative to their own country as part of JADECARE, including barriers, facilitators and the lessons learnt

Promote findings from the Digital Roadmap initiative case study to better understand what countries/regions are interested in transferring the intervention.

References

[18] Andersen-Ranberg, K. et al. (2020), “Abstracts of the 16th International E-Congress of the European Geriatric Medicine Society”, European Geriatric Medicine, Vol. 11/S1, pp. 1-309, https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-020-00428-6.

[26] Azzopardi-Muscat, N. and K. Sørensen (2019), “Towards an equitable digital public health era: promoting equity through a health literacy perspective”, European journal of public health, Vol. 29/3, pp. 13-17, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz166.

[25] Bol, N., N. Helberger and J. Weert (2018), “Differences in mobile health app use: A source of new digital inequalities?”, The Information Society, Vol. 34/3, pp. 183-193, https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2018.1438550.

[7] Centre for Innovative Medical Technology (n.d.), My Hospital.

[6] Centre for Innovative Medical Technology (n.d.), The GERI toolbox.

[29] Cruz, J., D. Brooks and A. Marques (2014), “Home telemonitoring effectiveness in COPD: a systematic review”, International Journal of Clinical Practice, Vol. 68/3, pp. 369-378, https://doi.org/10.1111/IJCP.12345.

[1] Danish Ministry of Health et al. (2018), A Coherent and Trustworthy Health Network for All - Digital Health Strategy 2018-2022.

[15] Det Digitale Sundhedscenter (2021), Det Digitale Sundhedscenter.

[17] Det Digitale Sundhedscenter (2018), “Digital Patientuddannelse Intern Evalueringsrapport”.

[27] Effective Public Health Practice Project (1998), Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies, https://www.ephpp.ca/quality-assessment-tool-for-quantitative-studies/ (accessed on 28 July 2021).

[2] European Commission (2018), “Abstract of best practices - Fiche for Good Practice on digitally-enabled, integrated, person-centred care”.

[37] European Commission (2018), Benchmarking Deployment of eHealth among General Practitioners (2018), https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/d1286ce7-5c05-11e9-9c52-01aa75ed71a1.

[24] European Commission (2017), Deliverable D3.5 - Final Evaluation Report: MASTERMIND, https://mastermind-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/MasterMind-D3.5-v1.0_-Final-evaluation-report.pdf.

[4] European Commission (n.d.), Joint Action on implementation of digitally enabled integrated person-centred care [JADECARE].

[31] Guaiana, G. et al. (2020), “A Systematic Review of the Use of Telepsychiatry in Depression”, Community Mental Health Journal, Vol. 57/1, pp. 93-100, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00724-2.

[16] Health Innovation Center of Southern Denmark (2021), The digital health centre – A partnership project, https://www.innosouth.dk/projects/the-digital-health-centre-a-partnership-project-1/ (accessed on 22 July 2021).

[10] Healthcare Denmark (2021), Digital Health, https://www.healthcaredenmark.dk/the-case-of-denmark/integrated-care-and-coherence/digital-health/ (accessed on 8 July 2021).

[5] Healthcare Denmark (2018), Denmark - a telehealth nation: White Paper, https://www.healthcaredenmark.dk/media/r2rptq5a/telehealth-v1.pdf.

[28] Hong, Y. and S. Lee (2019), “Effectiveness of tele-monitoring by patient severity and intervention type in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis”, International journal of nursing studies, Vol. 92, pp. 1-15, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJNURSTU.2018.12.006.

[36] ITU (2020), The ICT Development Index (IDI): conceptual framework and methodology, https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/publications/mis/methodology.aspx (accessed on 26 February 2021).

[13] MasterMind (2021), Region of Southern Denmark, https://mastermind-project.eu/partners/region-of-southern-denmark/ (accessed on 12 July 2021).

[20] Møller, P. et al. (2021), “Correction to: Development of patient-reported outcomes item set to evaluate acute treatment toxicity to pelvic online magnetic resonance-guided radiotherapy”, Journal of Patient-Reported Outcomes, Vol. 5/1, https://doi.org/10.1186/s41687-021-00333-x.

[19] Nissen, T. (2012), Evalueringsrapport genoptraen.dk, https://www.syddansksundhedsinnovation.dk/media/641174/evalueringsrapport_-genoptraen-dk-2-.pdf.

[35] OECD (2019), Health in the 21st Century: Putting Data to Work for Stronger Health Systems, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/e3b23f8e-en.

[33] OECD (2019), Individuals using the Internet for seeking health information - last 3 m (%) (all individuals aged 16-74), Dataset: ICT Access and Usage by Households and Individuals.

[11] Oliveira Hashiguchi, T. (2020), “Bringing health care to the patient: An overview of the use of telemedicine in OECD countries”, OECD Health Working Papers, No. 116, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/8e56ede7-en.

[34] OTN (2018), OTN Annual Report 2017/18, https://otn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/otn-annual-report.pdf.

[23] PA Consulting Group (2017), Business case for the nationwide rollout of telemedical home monitoring for citizens with COPD.

[14] Pedersen, C. et al. (2017), “Final Evaluation Report”, https://doi.org/10.1192/s1749367600005531.

[12] Rasmussen, S., S. Wentzer and E. Fredslund (2016), Psykologstøttet internetpsykiatrisk behandling af let til moderat depression Evaluering af demonstrationsprojekt i Region Syddanmark.

[3] Region of Southern Denmark (2021), WP8 (Digital Roadmap towards an Integrated Healthcare Sector - Region of Southern Denmark).

[32] Region Syddanmark (2021), Facts about the Region of Southern Denmark, https://www.regionsyddanmark.dk/wm230808.

[8] Sorknaes, A. et al. (2013), “The effect of real-time teleconsultations between hospital-based nurses and patients with severe COPD discharged after an exacerbation”, Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, Vol. 19/8, pp. 466-474, https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633x13512067.

[9] Sorknaes, A. et al. (2010), “Nurse tele-consultations with discharged COPD patients reduce early readmissions - an interventional study”, The Clinical Respiratory Journal, Vol. 5/1, pp. 26-34, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-699x.2010.00187.x.

[22] Vallejo-Torres, L. et al. (2016), “On the Estimation of the Cost-Effectiveness Threshold: Why, What, How?”, Value in Health, Vol. 19/5, pp. 558-566, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2016.02.020.

[38] WHO (2015), Atlas of eHealth country profiles: The use of eHealth in support of universal health coverage, Global Observatory for eHealth, https://www.afro.who.int/publications/atlas-ehealth-country-profiles-use-ehealth-support-universal-health-coverage.

[21] Witt Udsen, F. et al. (2017), “Cost-effectiveness of telehealthcare to patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: results from the Danish ‘TeleCare North’ cluster-randomised trial”, BMJ Open, Vol. 7/5, p. e014616, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014616.

[30] Yun, J. et al. (2018), “Comparative Effectiveness of Telemonitoring Versus Usual Care for Heart Failure: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis”, Journal of cardiac failure, Vol. 24/1, pp. 19-28, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CARDFAIL.2017.09.006.