The COVID-19 pandemic exposed structural weaknesses of our economies. Many of them were pre-existing challenges, which have increased the short-term costs of crisis and risk leaving long-term consequences on growth, wellbeing and sustainability. As the roll-out of vaccination gradually installs hope, policy focus should turn to recovery packages that provide the foundations for stronger, more equitable and sustainable medium-term growth. The 2021 edition of Going for Growth advises on country-specific structural policy priorities for the recovery. This chapter frames the main policy challenges and structural policy priorities along three main pillars: building resilience; facilitating reallocation and boosting productivity growth for all; and supporting people in transition. A key message from the pandemic is the marked increase in the attention to building resilience.

Economic Policy Reforms 2021

1. Structural policies to deliver a stronger, more resilient, equitable and sustainable COVID-19 recovery

Abstract

In Brief

Reinvigorating economic growth and ensuring its resilience, sustainability and inclusiveness are key as the world emerges from the COVID-19 pandemic. Meeting this objective requires adjusting structural policies to tackle pre-existing weaknesses and those arising from the pandemic:

COVID-19 exposed existing structural weaknesses in health care systems, social safety nets and public administration efficiency.

With the pandemic accelerating digitalisation, the lack of digital skills, access and digital infrastructure among parts of the population became more evident, reinforcing inequality dynamics.

Many economies were struggling with sluggish productivity growth, lack of quality job creation and the transition costs of restructuring before the pandemic. COVID-19 adds challenges related to low growth, increased risk of unemployment and bankruptcies, scarring effects on youth, and the aggravation of physical and mental health of the vulnerable.

Large-scale investment and support foreseen in recovery packages provide an opportunity to boost growth but also enhance resilience, inclusiveness and address environmental sustainability challenges.

Fiscal and monetary policies are already supporting the economies and financial market policies have a role to play, not least in dealing with the potential wave of bankruptcies. Nevertheless, it is structural policies that need to address the underlying challenges exposed by the pandemic and previous years of subpar growth. Going for Growth provides first-hand country-specific advice on structural policy priorities for the recovery. These can be categorised across three main dimensions:

Building resilience and sustainability: Structural policies can improve the first line of defence to shocks (health care and social safety nets, critical infrastructure), improve public governance and strengthen firms’ incentives to better take into account longer term sustainability considerations.

Facilitating reallocation and boosting productivity growth. Steering growth in a more durable, resilient and inclusive direction requires structural policy action to increase labour mobility and support firms becoming more dynamic, innovative and greener.

Supporting people through transitions. Policies should ensure that people are not left behind in transitions, so that reallocation is socially productive and builds resilience. This requires investments in skills, training and more generally easing access to quality jobs – particularly amongst vulnerable groups – and broad-based social safety nets that provide income assistance during transitions and incentivise learning and access to work.

Finally, international cooperation – spanning health care, climate change, trade and the taxation of multinational enterprises – can enhance the effectiveness of domestic policies and underpin the shift to more sustainable, resilient and equitable globalisation.

Going for Growth 2021 illustrates a new policy emphasis on resilience and environmental sustainability. Resilience is built through stronger growth, inclusiveness and the ability to reallocate resources swiftly, reducing harmful frictions that hamper the response to change. Addressing such challenges will enhance the efficacy of policy stimulus during the recovery and boost medium-term growth.

Structural policies for the recovery

The COVID-19 pandemic has wreaked havoc across the globe since early 2020, with over 2.7 million deaths on record by end of March 2021. Uncertainty about the health and economic prospects remains elevated at the time of writing, but the gradual roll-out of vaccination offers hope for some improvement in the coming months. When preparing and implementing policies for the recovery, policy makers have the opportunity to shape the quality and strength of post-COVID growth.

The pandemic caught many economies unprepared and existing structural weaknesses amplified the shock. Health care systems, often under pressure due to years of budgetary restrictions, proved ill-prepared for a global pandemic of such a scale. Patchy and ineffective social safety nets in many countries left people exposed to risks of poverty due to income loss. Limited digital skills and access to digital infrastructure became particularly evident and penalised many. A number of these problems weighed on growth prior to the pandemic, slowing productivity growth, population ageing and deepening inequality. COVID-19 adds new challenges. Increases in unemployment and bankruptcies threaten to scar the prospects of those struggling to enter or re-enter the labour market, while the lockdowns may widen education gaps and aggravate physical and mental health of the vulnerable in the longer term.

At the same time, the pandemic accelerated digital trends, which could also provide opportunities in terms of organisation of work and teaching, as well as consumption patterns. This will have long-term impact on the need for physical presence at a workplace for many, possibly leading to less commuting. In some sectors it brought disruptive innovation, and there are now high expectations that such disruption will entail a digital dividend. Similarly, the enhanced focus on resilience has made climate change concerns more acute. Against this backdrop, decisive policy action to reset growth is urgently needed.

From economic lifelines to higher quality growth

The extent of damage caused by the pandemic remains uncertain (Baker et al. 2020), but without strong policy action many temporary damages risk becoming long-term brakes on growth. Unsurprisingly, in 2020, governments focussed on addressing urgent pandemic-related issues. Structural policies can play a crucial role in shaping the recovery and bring long-lasting benefits.

The pandemic highlighted the lack of resilience

Structural weaknesses in many health care systems were unaddressed, despite increasing epidemiological warnings of the risk of pandemics due to shifts in and destruction of wild habitats, and rising global interconnectedness and urban density (OECD, 2011). Some Asian countries with past epidemic experience have coped better for example via early warning systems, stocks of personal protective equipment, and decisive testing, tracing and isolation. Still, in the absence of a medical solution restrictions on economic activity were the most common tool to slow the virus’ spread in many countries.

Pandemic-induced lockdowns highlighted gaps in social safety nets, leading governments to step in with massive, generalised policy support. COVID-19 hit low-income earners, informal and non-standard contract workers, women, migrants, children and youth, and those with disabilities and chronic health conditions particularly hard (OECD, 2020a, Caselli et al. 2020). These groups were already vulnerable prior to the crisis, with weaker coverage in social safety nets in many countries. As such, the pandemic risks undoing progress on labour market inclusion and poverty eradication.

Several other sources of vulnerability were highlighted by the pandemic. Concerns over temporary shortages in certain goods at the height of the pandemic underpinned increasing calls for governments to do more to avoid disruptions to production and provision of essential goods. Past experience shows that global production networks can be disrupted and play a role in the propagation of economic shocks across countries and industries (OECD, 2020b). But diversified global value chains (GVCs) can also mitigate shocks and help firms and countries to recover faster, for example in the supply of essential goods (Chapter 2). Vulnerabilities also emerge from digital security risks, which increase with digital transformation but also with the inefficiency and obsolescence of legal and judicial systems to pursue them.

The recession risks leaving lasting economic and social scars

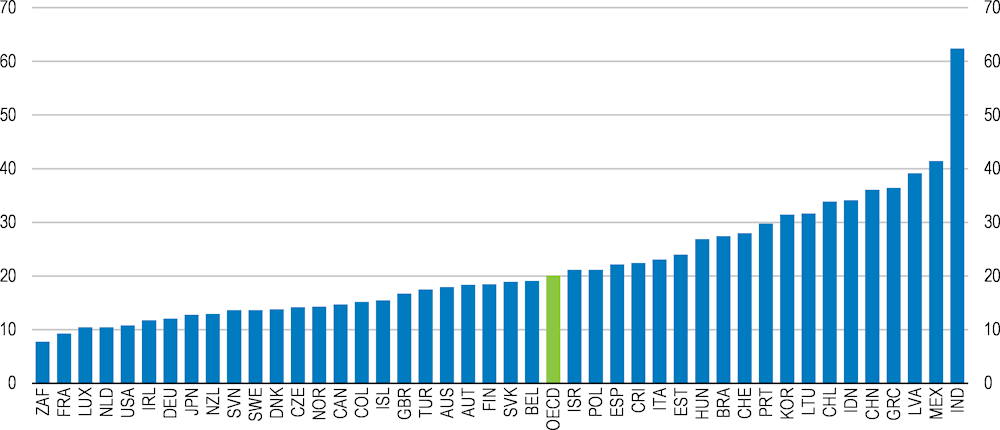

Labour market entry during a downturn carries persistent adverse consequences for individuals’ earnings and employment and the youth unemployment rate more generally (Figure 1.1, Panel A). New OECD cross-country evidence shows that labour market entry during a recession is associated with a larger absolute increase in the career unemployment probability for the least educated workers and women (Figure 1.1, Panel B) – two groups particularly exposed to the pandemic. But recessions also impart scars on highly educated workers, which are material relative to their lower baseline risk of unemployment. This may reflect the tendency for recessions to disrupt labour market matching (Barlevy, 2002), with those graduating into a recession tending to join (and remain in) lower productivity – and thus paying – firms (Andrews et al., 2020), which may causes skills to atrophy. Scarring may also emerge from school closures and the switch to online learning, disrupting human capital accumulation and hence lifelong earnings, particularly for students from disadvantaged backgrounds (Section: Policies to support people in recovery and transitions).

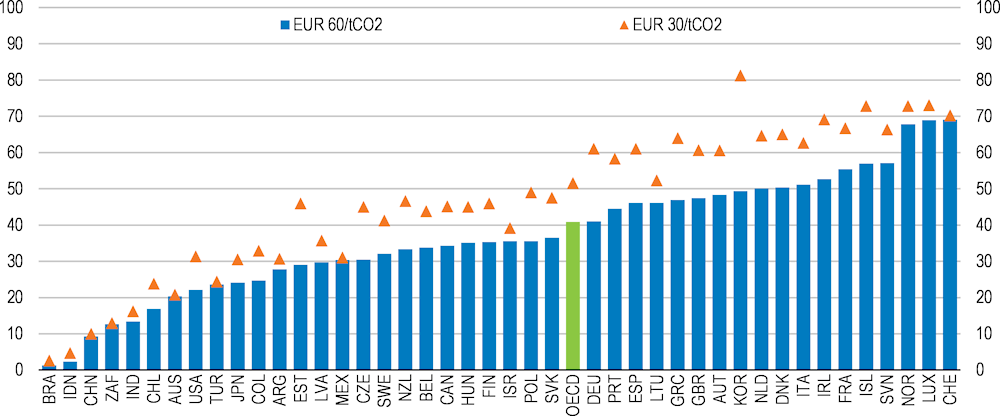

Figure 1.1. Recessions impart lasting scars on young workers

1. The chart shows the (predicted) difference in probability of unemployment for an individual who entered a weak labour market, defined as a youth unemployment rate that is 5.9% higher than usual (this corresponds to the average increase observed in our sample countries between 2007 and 2008), relative to an individual who entered during stronger economic times. On average, a worker entering such a labour market is estimated to have a 0.70 percentage point higher probability of unemployment throughout their career (Absolute impact), which amounts to an increase of 8% in the baseline risk of unemployment (i.e. relative to the sample average unemployment rate; Relative impact).1

Source: OECD, Labour Force Statistics Database and OECD calculations based on European Union Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS).

The pandemic is accelerating digitalisation

The pandemic has encouraged a wave of experimentation with novel modes of business, work and consumption from which new habits may form. Survey evidence from the United States and Europe suggests that working from home could increase substantially – due to both behavioural changes and new technologies that facilitate it – while business travel could permanently fall (Barrero, Bloom and Davis, 2020; ECB, 2020). More generally, accelerated digitalisation could present opportunities to revive productivity growth – via technological adoption and within-industry reallocation – but also challenges to inclusive growth by further reshaping the nature of work and potentially urban structures (Autor and Reynolds, 2020).

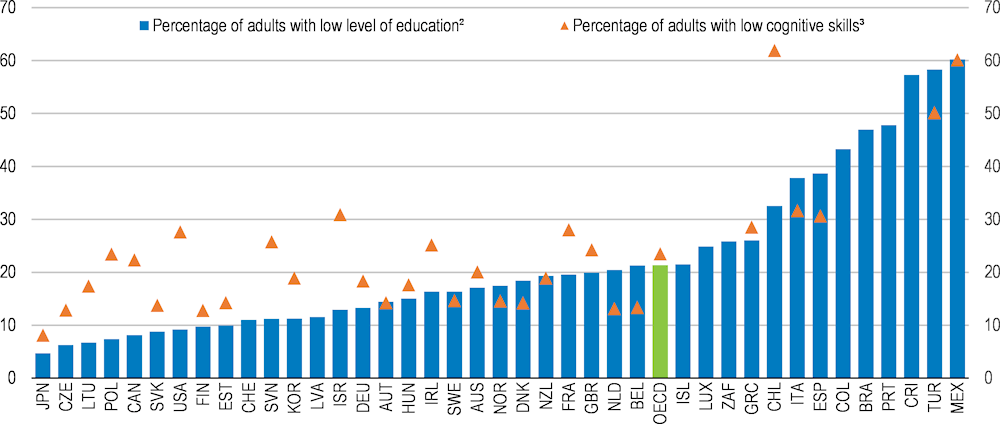

Pressures from automation – which is replacing routine and non-cognitive tasks in middle-skilled occupations – may increasingly be felt by the lower skilled, particularly women who are more likely to work in jobs that have high automation potential and risk of infection (Chernoff and Warman, 2020). The demand for certain tasks (e.g. those servicing inner city businesses) may fall, and displaced workers will need to face costly transitions to other occupations and sectors, with the pressure on policy to manage such reallocation (OECD, 2020c). This risks reinforcing inequality, especially if the new tasks created by automation benefit high-skilled workers, while low-skilled and non-standard workers – whose tasks are more prone to be displaced by automation – remain less likely to access reskilling policies (Acemoglu and Restrepo, 2020; OECD, 2019b).

The Green Transition adds restructuring challenges

The pandemic has put resilience at the core of peoples’ concerns (OECD, 2021a). In this respect, the recovery presents an opportunity to address the pressing challenge of climate change. Policy intervention and investments will play a key role in steering the transition: the initial drop in emissions as a consequence of the pandemic proved only short-lived, in December 2020 they were already 2% higher than the same month a year earlier (IEA, 2021). Annual global energy investment will need to roughly double until 2050 to achieve the Paris agreement’s climate targets (IEA, 2016). The transition towards global net zero emissions will hence rely on an acceleration in green innovation and the reallocation of resources across industries, but also between firms within a given industry – in order to underpin the rapid expansion of green and innovative firms – and within firms to commercialise and implement new ideas (Marin and Vona, 2019).

Part of the shift will be accommodated through the downsizing or exit of polluting firms and less productive ones that cannot accommodate such investment, which entails transition costs that are politically challenging (for an example on the phase-out of coal-fired power plants in Germany, see OECD, 2020d). This process can be costly for: i) workers in declining (i.e. polluting) sectors (Walker, 2013; Marin and Vona, 2019); and ii) firms in expanding (i.e. green) activities, if they encounter difficulties in hiring workers to fulfil their demand for green skills. These transition costs partly depend on the transferability of skills between green and polluting activities: task-based evidence suggests that the general skills requirements of jobs associated with polluting activities are often close to those of green jobs (Vona et al., 2018). But when workers cannot be reskilled and re-employed, they risk falling into unemployment or exiting the labour market. Countries that minimise obstacles to such reallocation – and carefully manage transition costs – will transition more smoothly.

Weak reallocative capacity risks deepening the scars from the pandemic

Weak reallocative capacity can imply that economies are poorly prepared to face any pandemic-related restructuring as well as the digital and green transitions, which may amplify scarring effects, mute wage and career prospects and hinder economic growth. Reallocative capacity and productivity growth were declining prior to the crisis, which has been partly attributed to structural policy weakness, including regulation-induced rigidities in services delivery (Andrews, Criscuolo and Gal, 2016; Hermansen, 2019) and corporate restructuring (Adalet McGowan, Andrews and Millot, 2017).

The economic vitality of OECD economies has been waning for some time with potential output per capita growth roughly halving since the late 1990s due to slowing TFP growth and capital deepening. This was underpinned by a divergence in the productivity performance of global frontier and laggard firms, which is symptomatic of barriers to: i) knowledge diffusion; and ii) creative destruction, whereby new firms enter and replace old ones, and resources are reallocated towards more productive firms (Andrews, Criscuolo and Gal, 2016). This trend coincided with increasing market concentration and mark-ups, – especially in digital-intensive sectors – raising concerns that market power was stifling inclusive growth.

This decline in market dynamism adversely affected workers. More fluid labour markets – characterised by higher voluntary job-to-job transitions – reduce the risk of long-term unemployment and can improve worker-job match quality, especially for young workers who are more prone to skill mismatch. More fluid labour markets can also improve bargaining power by increasing the number of outside options for workers to assert in wage bargaining negotiations (Karahan et al., 2017) and lower wage inequality (Criscuolo et al., 2021). This decline in job mobility suppressed wage growth and was connected to lower firm entry – as new firms create outside options – and higher product market concentration which amplified monopsony power. This strengthens the case for policies that support market competition, labour mobility and inclusion more generally.

Structural policies for stronger, more sustainable, resilient and equitable growth

Beyond the immediate crisis-related interventions – including the need to maintain highly accommodative macroeconomic policy settings for some time – policy focus should be on medium-term objectives in order to speed-up and shape a vibrant recovery. Structural policies can support economies ability to bounce back strongly and rapidly (Duval, Elmeskov and Vogel, 2007). But as outlined above, there is a case for advancing structural policies to achieve a recovery that also delivers more sustainable, resilient and equitable growth.

Policies to boost growth are particularly pressing given upward pressure on public expenditure, notably on public pensions and health care, coming from population ageing and rising relative price of services. Trend growth rates have generally declined due to demographic change and a slowdown in productivity growth. Public debt to GDP is projected to increase by a fifth between 2020 and 2022 (OECD, 2020c). Without structural reforms that boost growth, the ability of governments to deliver resilience and buffer future shocks may be limited. In similar vein, maintaining current public benefits and services while stabilising public debt ratios would require a substantial increase in taxation (Guillemette, 2021, forthcoming).

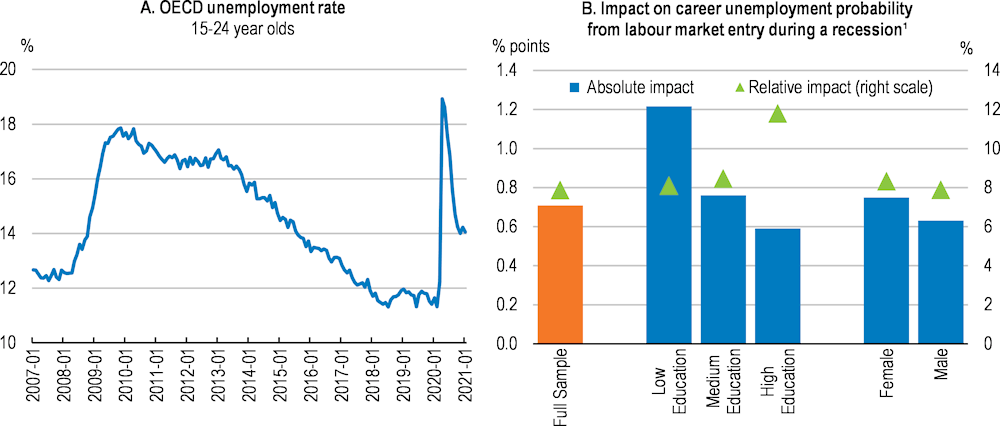

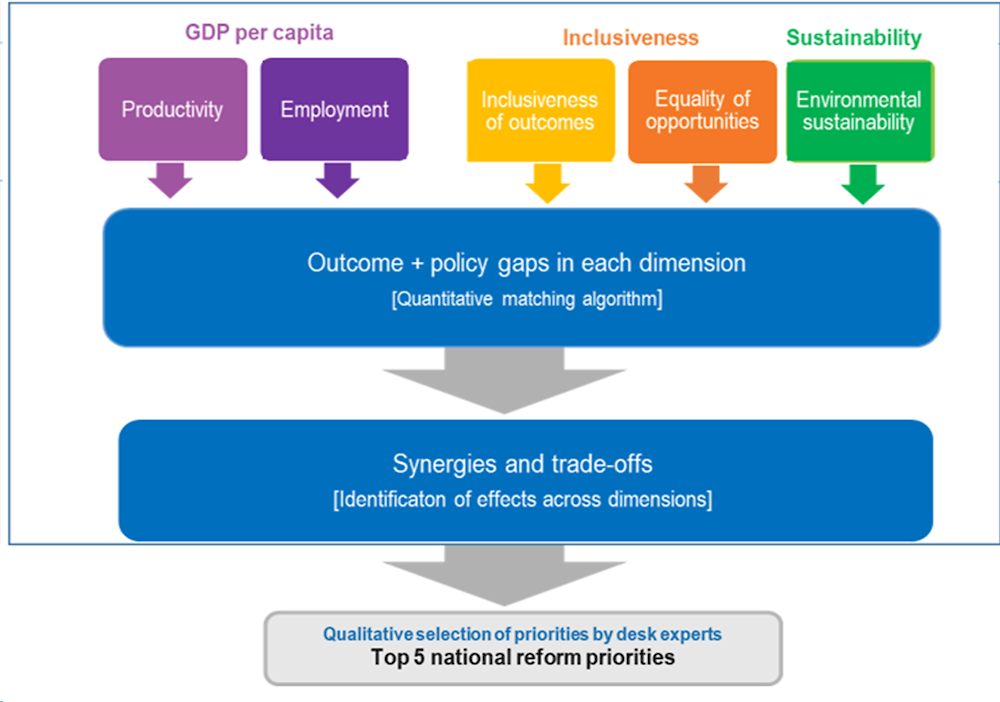

Going for Growth 2021 provides country-specific advice on how to achieve a recovery that delivers a stronger, more resilient, equitable and sustainable growth. The key structural challenges to be addressed are identified within the Going for Growth framework (Annex 1) by OECD Country Desk experts and presented as packages in the Country Notes. There is no one-size-fits-all strategy, but the overall objective is to make economies more resilient and to take a turn for change. To achieve this, policy advice can be described around three – often overlapping – pillars (Figure 1.2):

Building resilience and sustainability: Resilience is the capacity to detect and avoid risks, reduce the negative impacts of shocks when they materialise, and recover faster and stronger. Structural policies can improve the first line of defence to shocks (health care and social safety nets, crucial infrastructure) and strengthen the private sector’s incentives to take into account longer-term sustainability considerations, such as by directing investment and technological change to serve environmental objectives. Hence, resilience is also about reconciling short-term efficiency towards a perspective of stronger longer-term growth. These policies are discussed in Section: Policies to build resilience and sustainability.

Facilitating reallocation and boosting productivity. Steering growth in a more resilient and inclusive direction requires swift reallocation of resources. This means removing policy barriers, where they exist, for firms to become more dynamic, innovative and greener thereby facilitating the reallocation of resources, both within and between firms. Failure to reduce reallocation frictions can also reduce job opportunities, stifle innovation, limiting productive career prospects and technology adoption, thus hampering productivity growth (Section: Policies to facilitate reallocation and boost productivity).

Supporting people through transitions. Policies need to ensure that people are not left behind in these transitions, by reducing impediments to finding quality jobs and shortening the time to do so, thus enhancing resilience to shocks. These policies include skills and education, activation and retraining schemes – in particular targeted at vulnerable populations – but also social safety nets, which can provide income assistance during transitions. Such policies should provide adequate incentives for taking up opportunities rather than creating dependence (Section: Policies to support people in recovery and transitions).

Domestic policies are the key levers for recovery strategies. But the pandemic also highlighted the need for stronger international cooperation (OECD, 2020e). Several policy areas identified in the Country Notes, while requiring domestic policy action, could be achieved even more effectively and efficiently with international co-operation. Examples include health care and the manufacturing and distribution of health care equipment and vaccines, tackling climate change, taxation of multinationals in the digital economy, and reducing trade barriers. Motivated by the existence of cross-border spillovers, this edition of Going for Growth, presents for the first time structural policy priorities in these four key areas, with a view of making globalisation work better for all (Chapter 2).

Figure 1.2. Structural policies for a stronger, more resilient and inclusive recovery

What are the structural policy priorities for a vibrant recovery?

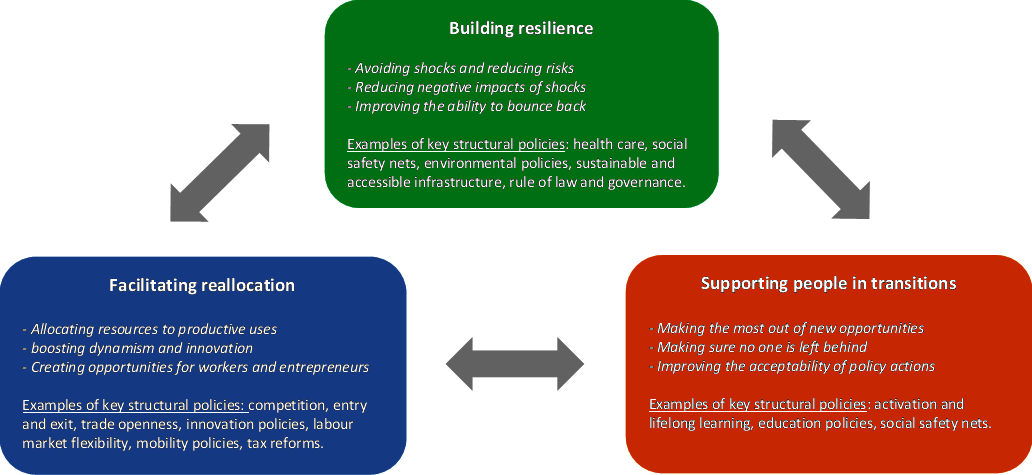

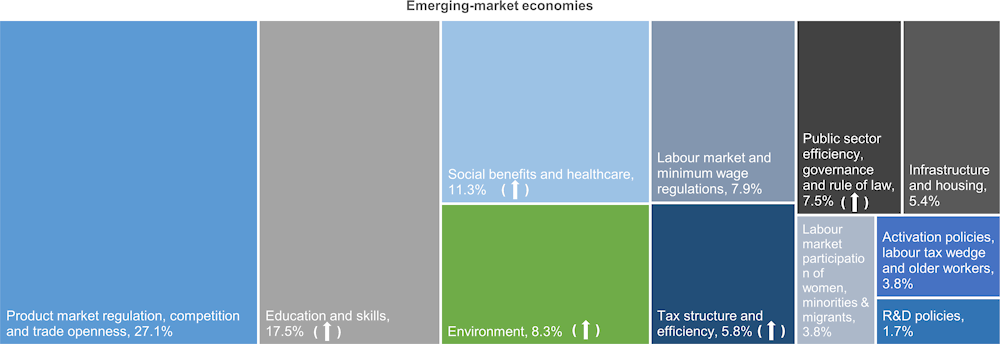

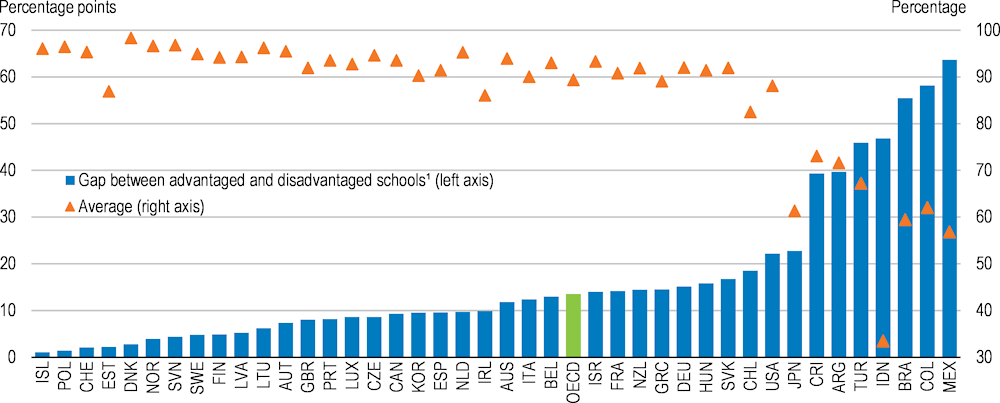

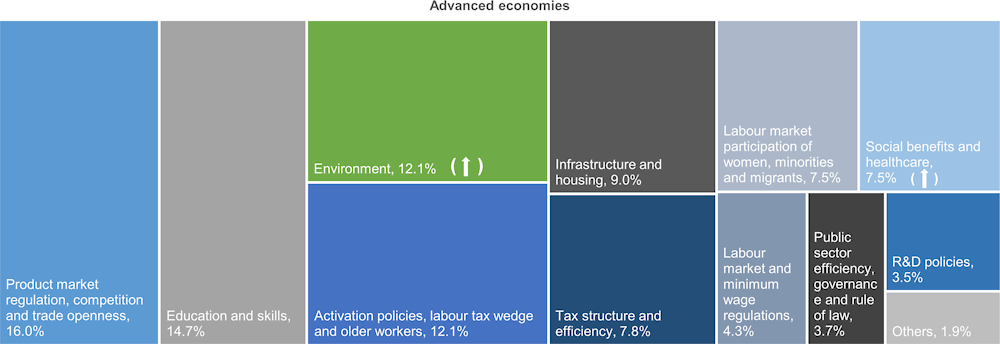

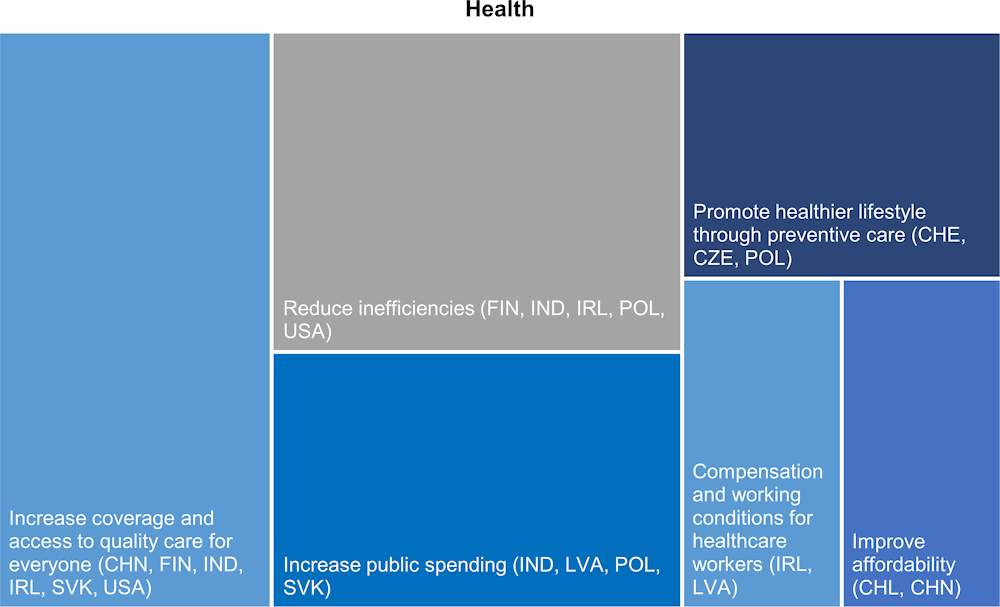

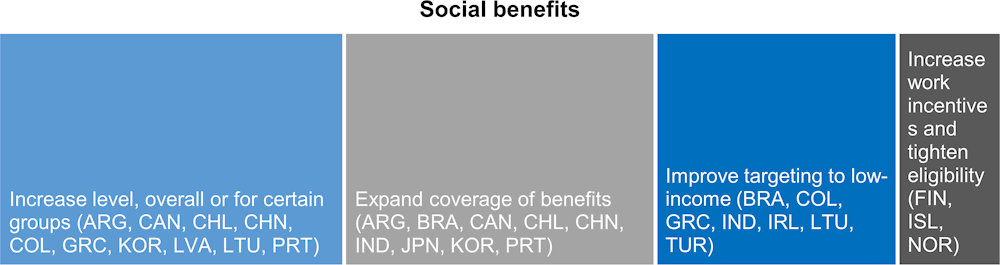

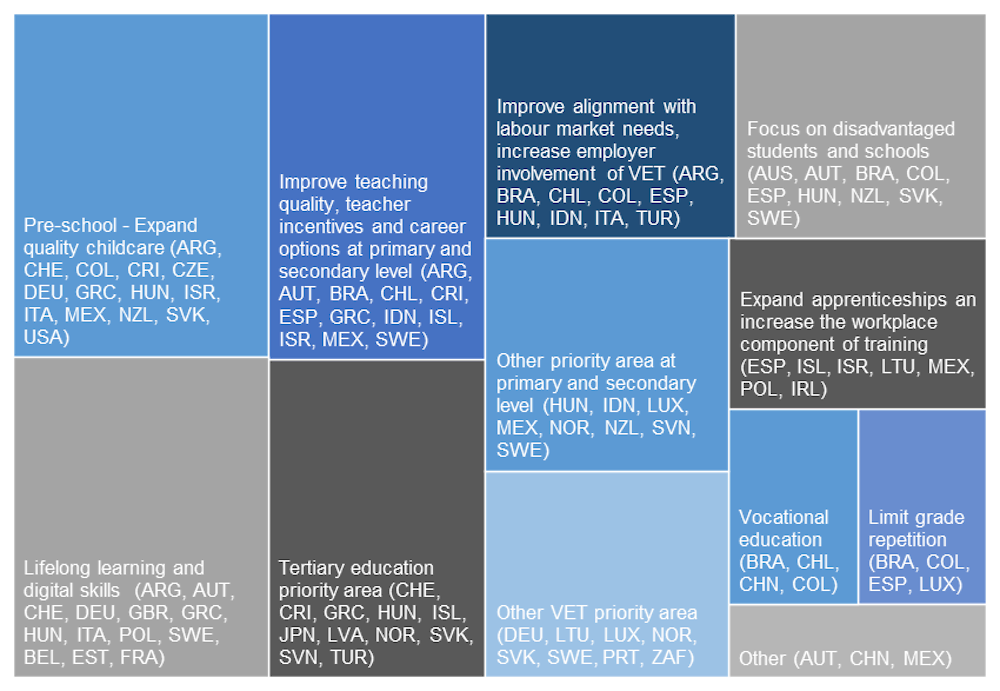

The broad priority areas primarily reflect the increased emphasis on resilience. The prominence of social safety nets and health care has increased in advanced and emerging-market economies2 (Figure 1.3), with a particular emphasis on inclusiveness. Environmentally motivated priorities have also gained importance in both groups of countries, likely as recovery policies constitute an opportunity to address long-standing environmental and climate sustainability issues (OECD, 2020f). In emerging-market economies, priorities addressing the rule of law, education and skills, and labour market regulations have gained importance, partly due to increased emphasis on informality.

Figure 1.3. Distribution of 2021 priorities across countries

Note: Upward-pointing arrows denote priority areas having increased their relative share in the distribution of priorities, with respect to Going for Growth 2019. In this publication, the group of advanced economies comprises all OECD member countries excluding Chile, Colombia, Mexico and Turkey. These four countries, alongside Argentina, Brazil, China, Costa Rica, Indonesia, India and South Africa are labelled as emerging-market economies.

Packaging structural reforms: Sequencing, synergies, trade-offs and state contingency

Given uncertainty about the shape of the recovery, the sequencing of reforms is vital.

Stimulating the recovery

Some structural policies are fiscally expansionary because they either necessitate higher spending or improve the effectiveness of fiscal stimulus. Rolling them out early can both stimulate the recovery and enhance long-term prospects:

Public infrastructure investment can stimulate demand. Projects that are already prepared and have high (social) return should be frontloaded. Examples can include the expansion of digital infrastructure that will improve the equality of opportunities or investments in transport or energy infrastructure in underdeveloped regions.

Reforms to improve people’s prospects – spanning education, rule of law and infrastructure governance – can boost confidence and people’s resilience to future shocks, even if their actual effects take time to materialise. Such policies enhance the effectiveness of fiscal spending.

Policies to address economic inclusion of poor households (e.g. health care and social safety net reforms) can raise the effectiveness of fiscal spending, as these households have a higher propensity to spend. Rapid actions to improve health care resilience – via increases in capacity and accessibility – can support recovery by expediting the vaccine roll-out.

Preventing significant and long-lasting social damage

Policies that prevent social damage – such as health, poverty and scarring – should be implemented with priority:

Education reforms take time to show macroeconomic gains but underpin health, poverty reduction and resilience. As ‘learning begets learning’, improvements at the pre-primary and primary levels will affect the ability of pupils to learn in later grades. Hence, education reforms need to compensate for the pandemic-related learning losses, particularly by ensuring that tele-schooling becomes an effective backstop option for all students, in case of future disruptions.

Preventive health care may bring most benefits later but improve resilience, as witnessed by the pandemic which hit harder those with pre-existing conditions or poor health.

Strengthening activation policies and skills will support those looking for jobs and accelerate their re-entry into the job markets, reducing scarring effects.

Gradual or state-contingent implementation

Other reforms should be implemented gradually, or linked to the state of the economy, as they may hamper the recovery:

Introduction or strengthening of job-search conditions in unemployment benefit schemes is important for job-search incentives, but should be state-contingent (i.e. vary with labour market conditions) as job opportunities may remain scarce initially in the recovery. Increasing stringency of eligibility criteria could force benefit recipients out of the labour force, which could increase the risk of poverty, undermine confidence and create uncertainty. Moreover, stringent unemployment benefits programmes need to be complemented with efficient activation policies (ALMPs) and public employment services that help job-to-job transitions.

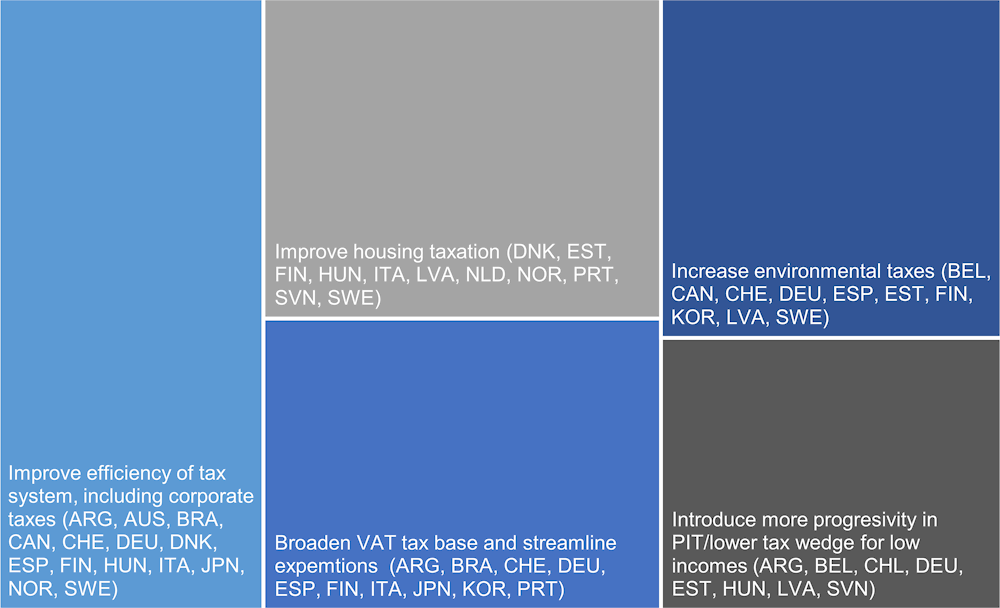

Reforms to achieve more growth-friendly tax structures require a gradual phasing-in and cautious approach in the recovery. Such reforms generally include reducing income taxes and shifting revenues to consumption, property and environmental taxes, as well as broadening tax bases. Fiscal sustainability concerns imply that these reforms should be implemented as a package so that they are budget neutral, but this still risks adverse consequences for consumption and inclusion. If such reforms are nevertheless required, personal income tax cuts and reductions of taxation for low-income workers should be brought forward, while government should commit to tax increases only once a durable recovery takes hold (OECD, 2020f).

Early commitment to increasing use of carbon taxes later in the recovery phase – with clear price trajectories – can provide forward guidance to investors, without immediately burdening businesses with new taxes (Van Dender and Teusch, 2020) and lower policy-related uncertainty, thus incentivising investment and innovation in low-carbon technologies (Dechezleprêtre, Kruse and Berestycki, 2021). To effectively manage expectations (e.g. on fiscal sustainability and on environmental taxation signals), the tax increases need to be planned and clearly communicated in advance, as well as be mindful of distributional effects.

Restructuring firms where governments took equity stakes during the crisis is complicated by the difficulty to value firms in such circumstances and the job losses associated with the restructuring (Arnold, 2018; Brown et al, 2019). Restructuring will need to be accompanied by early intervention focused on retraining (Adalet McGowan, Andrews and Millot, 2017). If firms remain state-owned (SOE), better and more transparent governance is needed. This can be done by firewalling the government’s role as an owner, which can improve the effectiveness of crisis-induced bailouts and the entire SOE portfolio (Abate et al., 2020). This will help ensure that SOE presence in markets does not disadvantage private sector competitors and undermine downstream competitiveness.

Increasing the flexibility of labour markets aids productivity-enhancing resource reallocation but during weak economic times, reducing employment protection legislation (EPL) can be contractionary (Section: Policies to facilitate reallocation and boost productivity). This may be particularly harmful in early recovery phases and in countries where reskilling policies do not support people to make use of the new opportunities. In this light, one option is to loosen EPL for new hires, while monitoring developments carefully.

Once the recovery is firmly in place, the post-crisis environment will provide an opportunity for countries to undertake a reassessment of their tax and spending policies along with their overall fiscal framework. Such a reassessment will need to take into account both the challenges brought to the fore by the crisis as well as those related to ongoing structural trends (e.g. population ageing, digitalisation, rising inequalities, the need to address climate change) in order to determine the mix and range of fiscal policies needed to deliver inclusive and sustainable economic growth over the longer term.

Policies to build resilience and sustainability

The first line of protection – reducing the human cost of the crisis

Health care systems

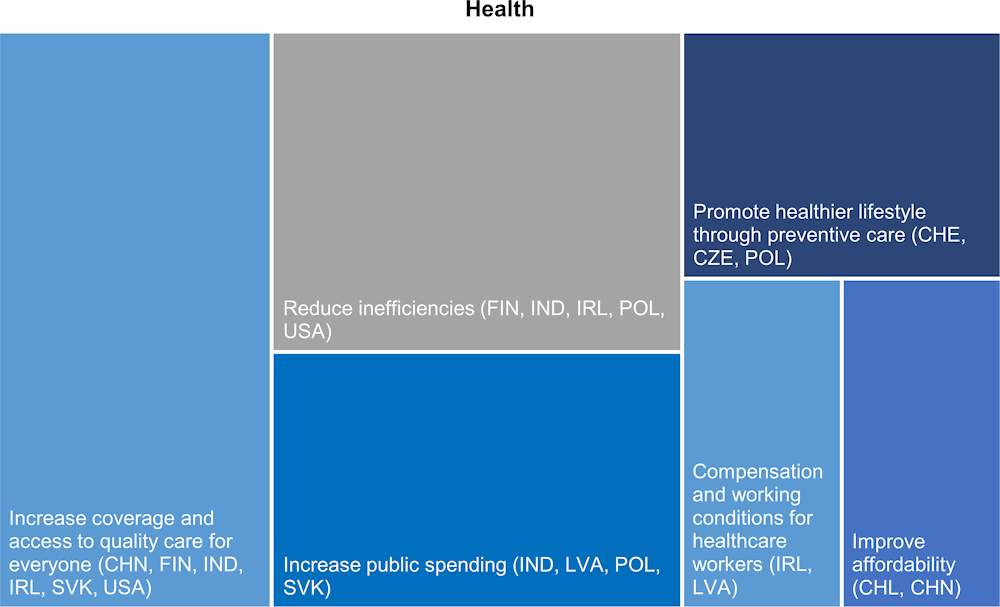

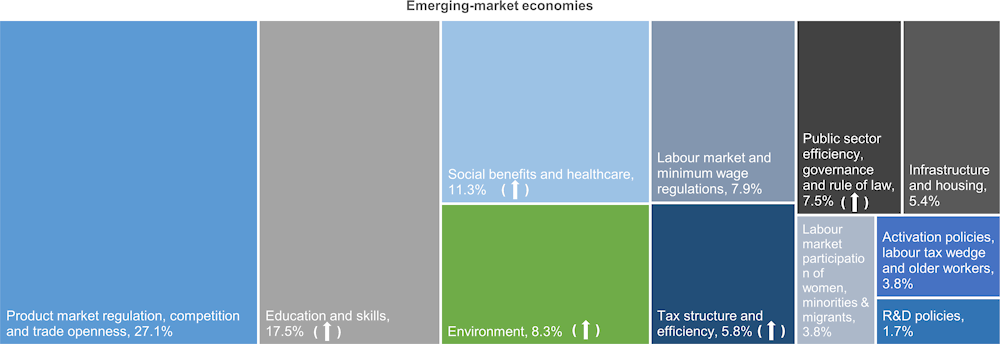

COVID-19 has highlighted structural weaknesses in many health care systems: weak resilience, shortages of health care workers, a lack of surge capacity, insufficient emphasis on prevention, a strong impact of social background on health outcomes and quality and safety issues in long-term care (OECD, 2020i, OECD, 2020j, OECD, 2020k). Health care is identified as a priority area in the recovery packages for 10 countries.

Considerable shares of the population do not have access to health care, especially in emerging-market economies (OECD, 2020g). But coverage for core services remains below 95% in seven OECD countries, and is lowest in Mexico, Costa Rica, the United States and Poland. In the United States, the uninsured tend to be working-age adults with lower education or income levels, while in Mexico lack of coverage is often linked to informality (OECD, 2020l). Most OECD countries have ensured access to and coverage of pandemic-related products and services.

High out-of-pocket payments can discourage early diagnosis and treatment, thus increasing the spread of diseases. For example, pre-COVD-19 figures show nearly 30% of people in the lowest income quintile (on average across countries) forgo care because of affordability issues (OECD, 2020g). In several countries, over one-third of health care spending is paid directly by patients (out-of-pocket payments) and serious illnesses can result in financial stress (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4. Out-of-pocket payments can be a significant part of healthcare expenditure

Household out-of-pocket payments as a percentage of current expenditure on health, 2019¹

Coverage needs to be increased permanently and ensuring equal access is a priority in several countries. Health care reforms should also focus on reducing out-of-pocket payments. The need to improve the overall quality of health care provision has become more pressing, particularly by addressing the lack of access to quality services in rural areas. Cost-efficiency remains crucial in light of resource constraints, but COVID-19 may lead to prioritising issues of reserve capacity, rapid warning and response preparation.

The pandemic is a reminder of the importance of prevention and the major contribution of environmental and lifestyle risk factors to chronic diseases, which increase mortality. In fact, chronic diseases have compounded the human costs of the pandemic, with severe cases of COVID-19 disproportionally affecting those who are obese or with pre-existing conditions. Some risk factors – e.g. smoking, alcohol consumption, poor nutrition, lack of physical activity and obesity – can be reduced by prevention-focused health policies (Figure 1.5). COVID-19 mortality also has a clear social gradient, a bleak reminder of the importance of the social determinants of health outcomes (OECD, 2020j).

Domestic policy responses to massive global health challenges, as demonstrated by COVID-19, can benefit from international cooperation: on containing the spread across borders, improving the resilience of health care systems, harnessing the spillovers from R&D and coordination on the distribution of medical materials, equipment and vaccines (Chapter 2. Cross-border priority note).

Figure 1.5. Key recommendations on health and social benefits

Note: Based on policy priorities identified in Country Notes.

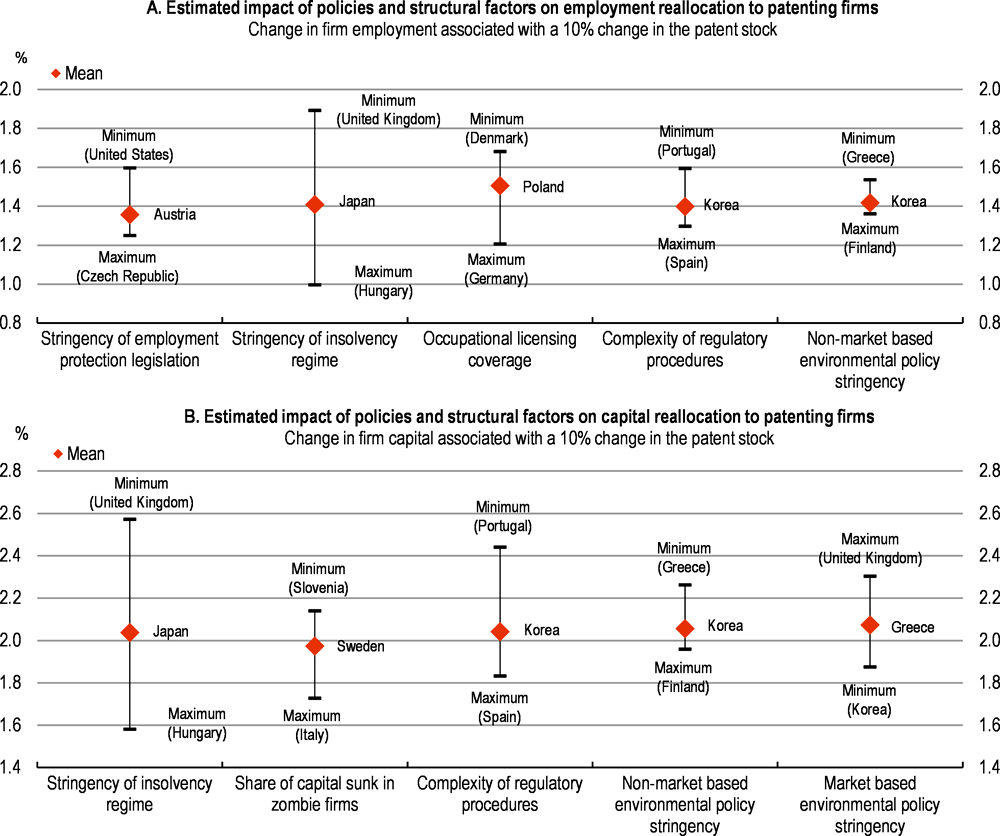

Social safety nets

The pandemic highlighted gaps and shortcomings of social safety nets, both in advanced and emerging-market economies. A shock can be particularly damaging if it pushes people into poverty or has persistent distributional impacts. Increasing resilience requires social safety nets that curb such effects and facilitate a swift return to work, in order to lower the risk of scarring (De Fraja et al, 2019).

Unemployment benefits are key instruments to provide income protection against job losses, yet, some workers do not meet the criteria to receive adequate support. Even when entitlements are the same for all dependent employees, conditions on minimum employment duration or earnings before the unemployment spell are often harder to meet for those on part-time jobs or those who frequently transition between work and unemployment (OECD, 2020a). Workers in informal and non-standard jobs often have less or no access to existing social protection (e.g. paid sick leave) and job loss can tip them into poverty.

Most governments stepped up income support to workers and households affected by the pandemic, extending health care coverage, unemployment benefits, minimum-income benefits and wage subsidies to self-employed, part-time and temporary workers, as well as to workers in other non-standard jobs (OECD, 2020h). In the United States – where only 43% of part-time workers are covered by an employer-provided paid sick leave plan, compared to 89% of full-time workers – part-time workers (including those in the “gig economy”) and the self-employed received access to up to two weeks of paid sick leave amongst other measures. Many governments also introduced temporary programmes to support self-employed workers and small firms, while some emerging-market economies (Chile, Indonesia and Turkey) have devised new schemes to support informal workers. There may be a case for institutionalising the new schemes to build a more resilient social safety net that can better react to extreme shocks.

Gaps in the social safety net coverage are partly linked to labour market dualism, a long-standing problem in several countries (Figure 1.A.3 in Annex A). Dualism between workers on permanent contracts and those on various types of non-standard contracts and between formal and informal employment often implies that the most vulnerable – with incomplete access to social safety nets – are hardest hit in downturns. The pandemic has also struck along this line of dualism, with non-standard workers accounting for around 40% of total employment on average across European countries in the sectors most affected by containment measures (e.g. tourism, entertainment, retail; OECD, 2020i). This may further exacerbate women’s exposure to shock (Section: The pandemic is accelerating digitalisation) given that women are often more likely to have non-standard work contracts. Moreover, the pandemic presents further challenges to duality – given the growing importance of the gig economy – and more generally the quality of jobs (OECD, 2020i).

In a dual labour market, such shocks will aggravate income inequalities and reduce equality of opportunity. For instance, the urban-rural divide remains an important source of inequality of access to social security, education and job opportunities in China. In the United States, much health care coverage is linked to formal jobs. Income poverty has long lasting effects on well-being of whole families, jeopardising future economic prospect of children. To reduce such divides, longer-term solutions are needed. Broader based access to social protection could increase job quality and reduce labour market inequalities.

Mitigating future risks through an environmentally sustainable recovery

The pandemic has raised awareness of environmental challenges such as climate change, pollution and associated health costs, biodiversity loss and water scarcity. Recovery strategies present an opportunity to put growth on a more sustainable path, and to accelerate a Green Transition (OECD, 2020c). Left unaddressed, environmental pressures seriously threaten current wellbeing: each year well over 4 million people die from air pollution, natural disasters have more than doubled in the past two decades and biodiversity loss is already threatening human health and economic prosperity (CRED-UNDRR, 2020).

Environmental priorities saw a marked increase among Going for Growth policy recommendations (Figure 1.6). Addressing environmental sustainability – specifically in the domain of climate change – are now a priority for 17 countries and the European Union. In this respect, most countries are advised to prioritise “green” public investment and subsidies, especially early in the recovery. In addition to the countries with outright environmental priorities, a commitment to future rises in environmental taxes – to instigate behavioural changes and as “forward guidance” for investors – is advocated for another 14 countries. This reflects the fact that strong and stable price signals, e.g. on carbon pricing, are still lacking (Section: Directing and facilitating a green recovery). Finally, several countries should phase out or reform agricultural subsidies, including in a way so that they incentivise more environmentally sustainable outcomes.

Figure 1.6. Key recommendations on green growth

Note: Based on policy priorities identified in Country Notes.

To address concerns of leakage across borders, which could disrupt the global level playing-field, and to improve the effectiveness of innovation policies, climate change mitigation requires co-ordinating actions across countries (Chapter 2). More generally, while environmental policies can direct behaviour, consumption and innovation, a successful transition will require reallocation of resources in line with the new incentives set by policies (Section: Directing and facilitating a green recovery).

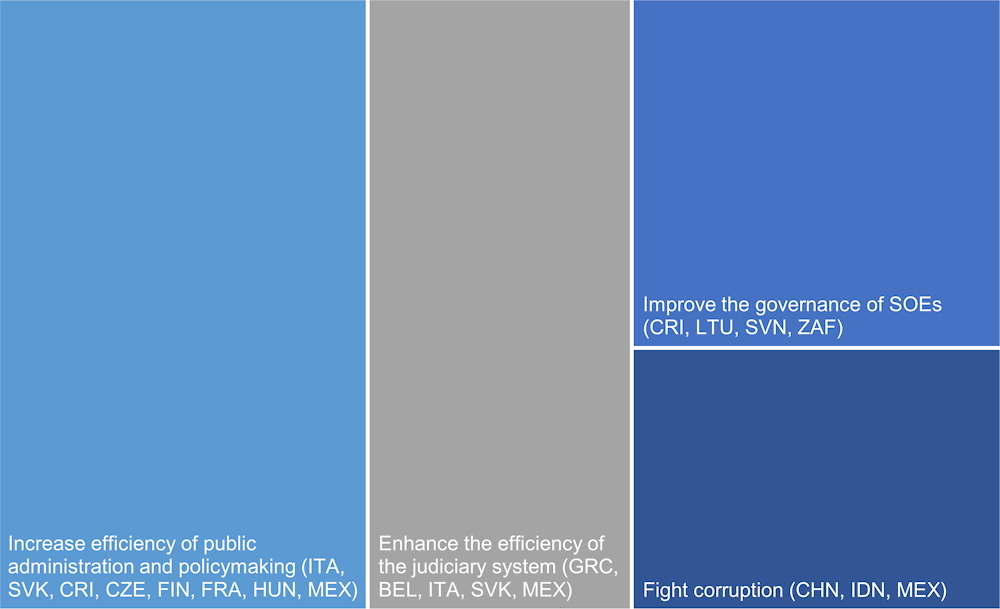

Enhancing trust and credibility with public governance and rule of law

Emerging research suggests that areas with high trust in public authorities had better compliance with stay-at-home restrictions during the pandemic (Bargain and Aminjonov, 2020; Brodeur et al 2020). A lack of confidence in government coupled with growing disinformation linked to the pandemic may hinder the effectiveness of the roll-out of vaccines, health measures enacted to limit the virus and economic recovery policies (OECD, 2020p). As the social fabric will have been harmed by the economic consequences of the pandemic, and state intervention in the economy increased, strong governance will be even more important.

More generally, public sector efficiency, rule of law and good governance are key determinants of confidence in public institutions, with important implications for productivity (Egert, 2017) and public support for – and ultimately success – of reforms (OECD, 2017a). Public trust can also lead to greater compliance with regulations and tax systems (OECD, 2013). Their absence, manifested through corruption, weak legal accountability and legal delays, can undermine growth by diverting scarce resources from their most productive use. Public governance has been a long-standing challenge for many countries, as identified in past editions of Going for Growth.

The pandemic added urgency to improving public governance in state-owned enterprises (SOEs), as equity injections in businesses were often part of the emergency measures taken to sustain the economy (Abate et al. 2020). Public ownership is prevalent in many OECD economies, and adequate, arm’s-length regulation in line with the 2015 OECD Guidelines are crucial to ensure performance of SOEs and maintain a competitive landscape (Abate et al. 2020; EBRD, 2020).

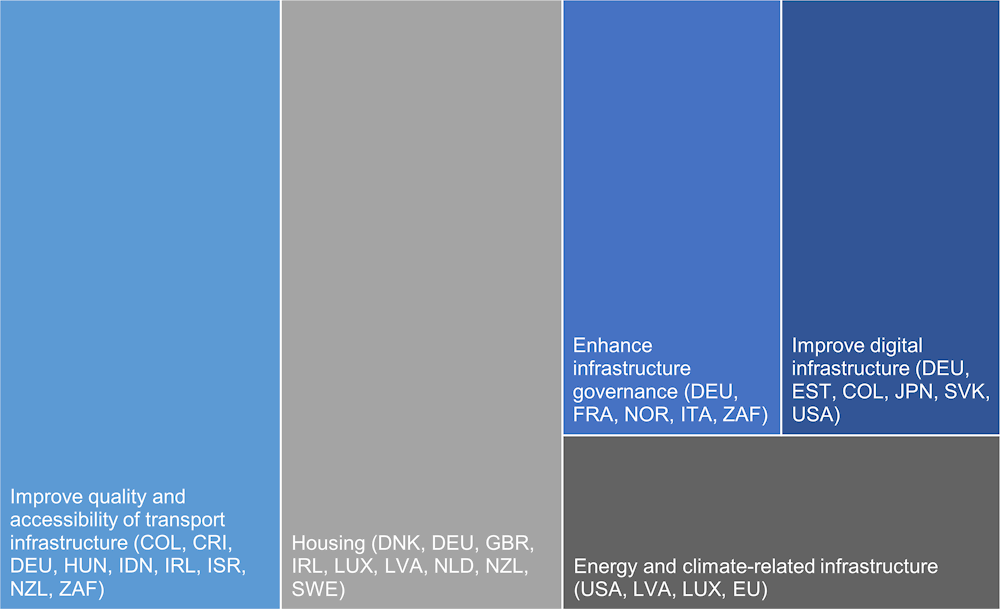

Improving resilience and well-being through infrastructure

The pandemic highlighted the benefits of reliable digital infrastructure for resilience. Infrastructure investment can also enhance economic performance and well-being in the medium term. Investment needs were already large before the pandemic, with public capital relative to GDP flat or falling over the past decade and infrastructure quality deteriorating in a number of OECD economies. Similarly, the stock of infrastructure in emerging-market economies remains insufficient to supply universal access to basic amenities such as electricity, water and sanitation, needed to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals (Rozenberg and Fay, 2019). On top of these, the Green Transition requires a substantial investment, particularly in clean energy and transport infrastructure.

Public infrastructure investment can also provide effective short-term demand stimulus, particularly where there is economic slack and fiscal multipliers are higher (Abiad et al, 2015, Schwartz et al, 2020). With long-term interest rates low, the social rate of return on public investment is likely to exceed financing costs for many projects. But the aggregate benefits of infrastructure investment depend upon effective: i) project selection; and ii) planning, delivery and management of projects (Box 1.1).

There is scope to improve digital infrastructure – particularly in rural areas – in all countries. Moreover, physical infrastructure continues to hamper inclusive growth in a number of countries. Insufficient transport infrastructure can create traffic bottlenecks, and raising citizens’ exposure to pollution. Addressing these gaps should be part of the recovery strategies in Colombia, Costa Rica, India, Israel and South Africa, as infrastructure deficiencies often restrict access to job opportunities and health care. In other countries, including the advanced ones, infrastructure governance can be improved.

The pandemic also renewed concerns about overcrowded housing, which has undermined the effectiveness of: i) self-isolation protocols, thus propagating the spread of the virus; ii) working from home; and iii) online schooling (OECD, 2020q). Housing also shapes resilence. Housing policy reforms that remove barriers to geographic or job mobility can mitigate the scarring effects of recessions (Section: Remove barriers to labour mobility) and create opportunities to climb the socioeconomic ladder (Judge, 2019), thus enhancing inclusive growth. In Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands, much emphasis remains on reducing policy-induced housing market distortions. Finally, rising housing costs disproportionately burden low-income households (OECD, 2020q) – with housing affordability and quality a persistent issue in cities in Germany, Latvia, and United Kingdom. Housing can also pose risks to macroeconomic stability by raising household debt.

Box 1.1. Good infrastructure governance can deliver substantial benefits

On average, more than one-third of the resources spent on creating and maintaining public infrastructure are lost due to inefficiencies and better governance could make up half of the efficiency losses (IMF, 2015; Schwartz et al, 2020). If a country moved from the lowest to the highest quartile in public investment efficiency, it could double the impact of public investment on growth (IMF, 2015). Sound public infrastructure governance is also associated with higher productivity growth at the firm-level in upstream sectors and in downstream sectors (such as utilities, transport and communication; Demmou and Franco, 2020). Stronger infrastructure governance is associated with higher levels of efficiency, less volatile investment flows and lower levels of perceived corruption (Schwartz et al, 2020).

Institutional design of infrastructure governance is often better than effectiveness of the system itself (Schwartz et al, 2020). Gupta et al (2014) found that project selection and implementation are particularly important contributors to public capital and economic growth among low income countries, while for middle-income countries it was the appraisal and evaluation that mattered the most.

Policies to facilitate reallocation and boost productivity

Recessionary episodes over the past 40 years demonstrate that losses to potential output tend to be smaller in environments which more readily accommodate reallocation (Ollivaud and Turner, 2014). Increasing pressures for restructuring may arise from the interaction of pandemic-induced changes and digitalisation and the Green Transition. But the apparent decline in the reallocative capacity of OECD economies may increase the costs of adjustment, raising questions about the ability of current structural policy settings to effectively navigate this reallocation challenge. The pandemic may intensify this challenge if crisis policies that protected the economic structure during lockdowns become entrenched which risks exacerbating scarring effects for younger workers, and market concentration further rises with liquidations.

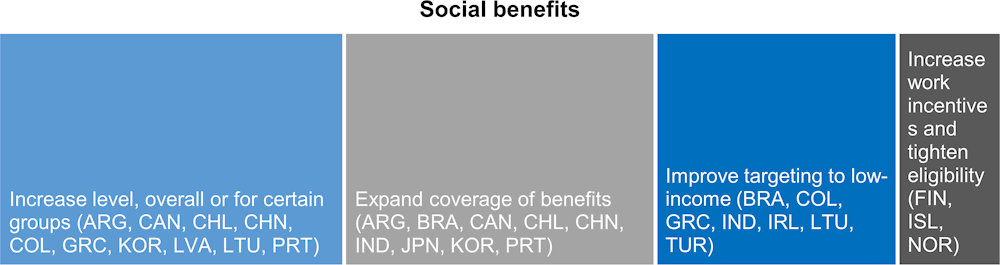

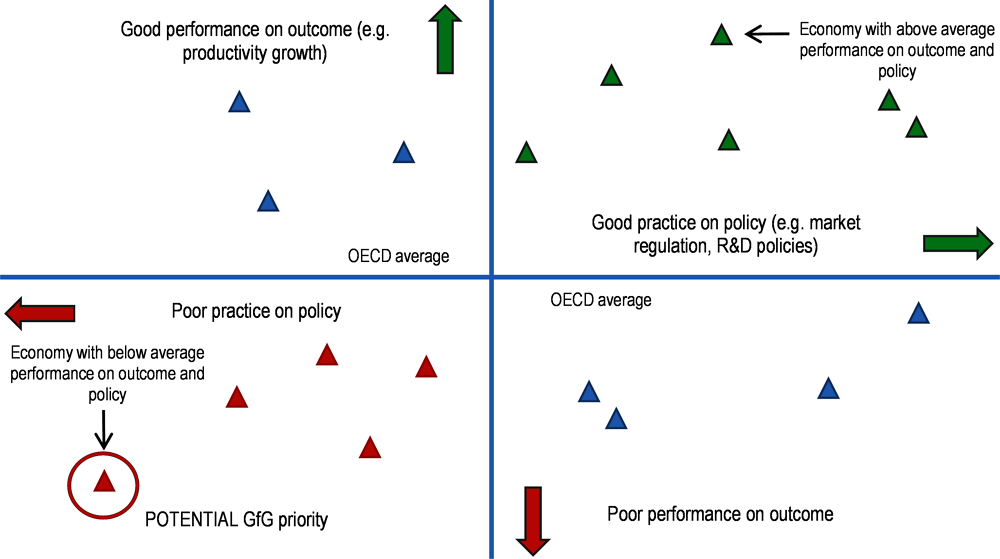

A speedier recovery will depend on the ability of economies to adjust to the organisational changes induced by the pandemic and undertake the restructuring necessary to embrace digitalisation, adapt to ageing and make progress on environmental goals. In this context, a key issue is the ease with which innovative firms can attract the complementary tangible resources – i.e. scarce capital, labour and skills – to test, implement and commercialise new ideas and eventually produce at a commercially viable scale. One metric of this process is the extent to which patenting firms can attract resources and grow, relative to other firms within industries, after controlling for country-specific industry level shocks (Andrews, Criscuolo and Menon, 2014). For the purposes of this chapter, this analysis was updated. On average across countries, a 10% increase in the firm patent stock is associated with a 1.4% increase in employment and a 2.1% increase in the capital stock (Figure 1.7) and evidence suggests a causal link between patenting and firm growth (Andrews, Criscuolo and Menon, 2014). But as discussed below, this process of resource reallocation to innovative firms varies significantly with the structural policy environment.

Figure 1.7. Well-designed policies can support resource reallocation to innovative firms¹

1. The charts show how the sensitivity of firm employment (Panel A) and capital (Panel B) to a 10% increase in patent stock varies with the policy environment and structural factors based on the methodology in (Andrews, Criscuolo and Menon, 2014).3

Source: OECD calculations based on Andrews, Criscuolo and Menon (2014).

While a range of reallocation-friendly policies can support trend productivity growth, their impacts on short-run aggregate demand can vary. Priority should be given to those reforms that can be expansionary in the short run (Caldera Sánchez, de Serres and Yashiro, 2016) by removing impediments to firm entry, competition in market services and job mobility. Other examples include adapting competition policy for the digital age and some reforms to insolvency regimes. These reallocation-friendly reforms should be accompanied by policies to support workers (Section: Policies to support people in recovery and transitions) as they may lead to job displacement.

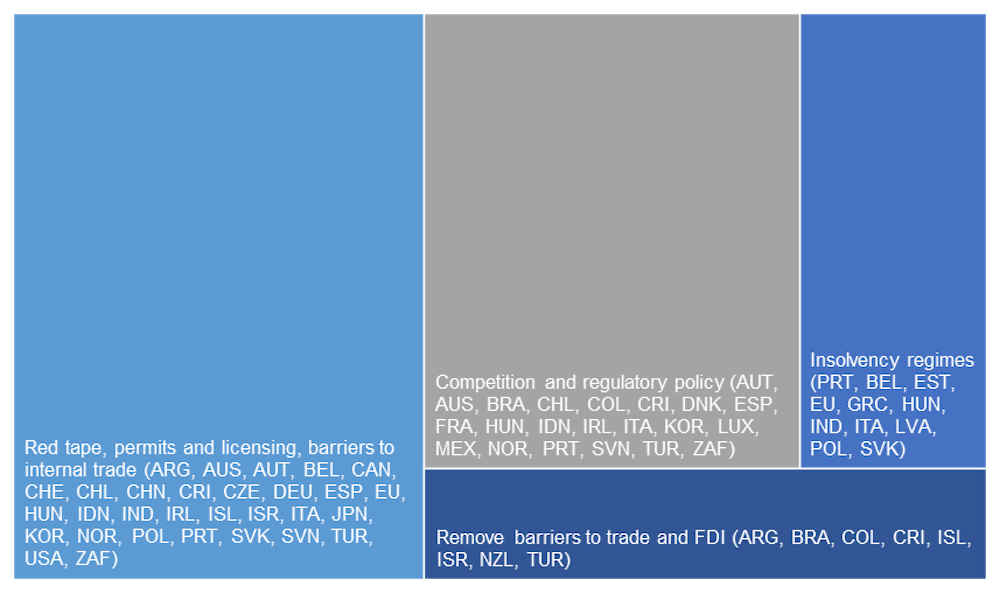

Removing obstacles to reallocation

Reduce barriers to entry

Market services have been particularly disrupted through pandemic-induced lower activity and changes in business models. More generally, this sector is relatively sheltered from competition in many countries. Stringent licensing and permits systems also create administrative burdens and regulatory complexity for firms in many countries. New OECD evidence suggests that reducing the complexity of regulatory procedures from the average level in Korea to the low level in Portugal could raise capital reallocation to innovative firms by 20% (Figure 1.7, Panel B).

Reducing entry barriers in service sectors with large pent-up demand and low entry costs can unleash firm entry, with the investment and employment gains materialising quickly (Forni, Gerali and Pisani, 2010). Such reforms can potentially leverage pent-up demand for some services as restrictions are lifted in the aftermath of the pandemic. Reducing economy-wide administrative burdens on firms can also improve expectations on future business conditions and spur firm entry, as evidenced from Southern Europe during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC, Ciriaci, 2014). Entry of new firms can help accommodate the organisational changes induced by the pandemic and the emergence of green technologies, as young firms have a comparative advantage in implementing radical technological and organisational innovations (Henderson, 1993). Reforms to entry barriers in the services features as one of the top priorities for many advanced economies, including Australia and United States as well as Indonesia (Figure 1.A.7).

Eliminate barriers to trade

Despite several major trade agreements and a noticeable increase in trade-facilitating measures over recent years, many distortionary barriers to trade remain (OECD, 2020o). Trade tensions between major economies have raised the need for policy action and several emerging-market economies continue to impose trade barriers that limit local firms from tapping into wider export opportunities (Argentina, Brazil, India). Multilateral cooperation (see Chapter 2) is crucial to grasp the benefits of lower trade barriers, which can provide opportunities to tap into markets that have recovered, thus supporting domestic employment, while spurring knowledge transfer and productivity growth over the longer run. Such policies should be coupled with well targeted support for workers who suffer from long-lasting displacement and lower earnings as a consequence.

Adapt competition policy for the digital age

Enhancing competition policy is one of the most frequent recommendation in the area of product markets regulation (Figure 1.A.7). The pandemic further highlights the need to adapt policy for the digital age. The shock has accelerated the shift in activity towards online marketplaces, thereby: i) sustaining production while traditional economic activities were severely disrupted; ii) reducing transaction costs, information asymmetries and entry costs for new providers with potential benefits for productivity; and iii) delivering services – e.g. low-cost logistics and payment services – that may especially benefit SMEs. While this may level the playing field between large and small firms, network effects can give rise to winner-takes-most dynamics that undermine competition against a backdrop of rising demand for digital services. Moreover, the assignment of data property rights to firms – as opposed to consumers – reinforces the high switching costs that result from network effects and the tendency for incumbent firms to hoard their data, stifling competition from start-ups that require access to data to train their algorithms. Recently, anti-trust cases against digital companies with substantial market power have been initiated by the US public authorities and the European Commission, while the European Commission also proposed for a new rulebook on digital services.

Competition authorities should pay attention to: i) new acquisitions by large technology firms (Cunningham, Ederer and Ma, 2018) and conglomerate mergers – i.e. between firms that are not current competitors, but may have products in related markets – which are more likely to occur in digital markets; ii) anti-competitive conduct by digital firms, including abuses of dominances or monopolisation (OECD, 2020r); iii) demand-side characteristics in markets, such as consumer behavioural biases (Fletcher, 2016); iv) the potential harm to follow-up innovation in their deliberations, since anti-competitive practices in digital markets are not always detectable in prices (OECD, 2018b); and v) placing the burden on dominant firms to show the consumer benefits of mergers and acquisitions (OECD, 2019c).

Remove barriers to labour mobility

Reducing barriers to geographic or job mobility can increase the speed of employment gains in difficult times. Reforms to reduce transaction taxes on housing purchases, the stringency of rental regulation and housing supply frictions can promote residential mobility and labour match quality (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2015), which is crucial to mitigating scarring effects. There is also much scope to reduce the stringency of occupational licensing and the fragmentation of regimes within countries, which can boost job mobility, diffusion and productivity (Bambalaite, Nicoletti and Von Rueden, 2020). For example, reducing workforce coverage of licensing regimes from the high level in Germany to the average level in Poland could boost labour reallocation to innovative firms by 25% (Figure 1.7, Panel A).

Caution is warranted when reducing the stringency of EPL early in the recovery. By reducing labour adjustment costs, such reforms can channel resources to innovative firms (Figure 1.7, Panel A) but they may prove contractionary in weak economic times if they trigger immediate layoffs, while only gradually increase hiring over time (Duval, Furceri and Jalles, 2020). For this reason, reforms to housing markets and occupational licencing should take priority.

Reform insolvency regimes and promote access to finance

The exceptional magnitude of the crisis and high levels of uncertainty firms face about the shape of recovery (in particular in sectors where demand may have decreased permanently) could push viable firms into liquidation, especially smaller enterprises. Moreover, insolvency frameworks tend to be less efficient in times of crisis, especially when courts get an increased caseload.

These headwinds strengthen the case for reforms to insolvency regimes that reduce the cost of entrepreneurial failure and barriers to corporate restructuring, even if crisis have so far kept insolvencies at artificially low levels. This would help to foster efficient capital reallocation and the restructuring of zombie firms that hamper productivity growth (Andrews, Adalet McGowan and Millot, 2018). New OECD evidence shows that such reforms to insolvency regimes may also help support the growth of innovative firms (Figure 1.7). Reforming insolvency regimes is among the top five priorities for a number of countries, such as Greece, India, Italy, Latvia, Portugal and the Slovak Republic (Figure 1.A.7)

More specifically, given the risks of a corporate debt overhang to investment, insolvency regimes should assign priority to new financing ahead of unsecured creditors but some countries do not offer any priority to new financing (Estonia, Hungary, Norway). It is important to strike a balance, however, as assigning priority to new financing ahead of secured creditors – as occurs in Belgium, Italy and Portugal – risks adversely affecting credit supply (Adalet McGowan and Andrews, 2018). There is also scope to promote pre-insolvency frameworks and simplified (out-of-court) procedures for SMEs in many counties, including Greece, Latvia and the Slovak Republic. Long discharge periods and the lack of a “fresh start” in personal insolvency regimes – i.e. the exemption of future earnings from obligations to repay past debt due to liquidation –overly penalise entrepreneurial failure in Belgium, Estonia, Hungary, Portugal and Norway.4 This is crucial to mitigate scarring effects as lenders – prior to incorporation – often require personal guarantees or collateral, meaning that corporate insolvency often leads to personal insolvency.

These reforms could be deployed with tools to support equity financing to recapitalise firms and mitigate debt overhang via measures such as equity and quasi-equity injections (e.g. preferred stocks), phasing in an allowance for corporate equity and debt-equity swaps (OECD, 2020s). This aims to reduce the number of viable and productive firms that would be otherwise liquidated, while encouraging the timely restructuring of unviable firms. But other crisis-induced changes to insolvency regimes – e.g. moratoriums on debt restructuring and the suspension of provisions that prevent trading while insolvent – should be regularly reviewed to ensure that they do not become a permanent impediment to reallocation.

As policy stimulus is withdrawn, reforms to diversify the source of corporate financing away from bank lending towards market-based debt and equity financing can help spur productivity growth, given that investments in new knowledge are more reliant on equity financing. In fact this is a priority for Austria. Well-functioning financial markets can bring forward the gains from reforms by facilitaing income smoothing – both to anticipate future gains and to offset temporary income losses – and financing investment.

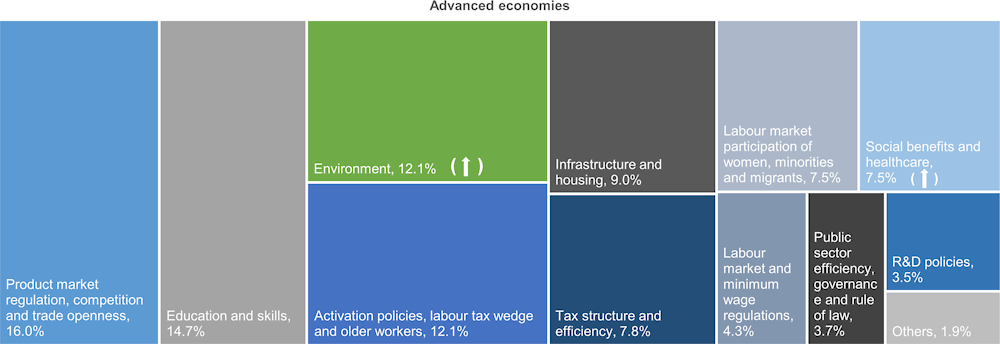

Directing and facilitating a green recovery

While the recovery from the GFC had not put the world on an environmentally sustainable path, this need not to be the case today. The pandemic could trigger behavioural changes in the way people work, travel and trade and adequate policies can ensure that such behavioural changes lead to permanent environmental improvements. To anchor long-term growth to a green path, strong and stable price signals are necessary but lacking (Figure 1.8). Most emissions are currently under-priced: in the 44 OECD and G20 countries, responsible for 80% of global emissions, 81% of emissions are priced below EUR 60/tCO2 (OECD, 2021c).

Early commitment to the increasing use of carbon taxes later in the recovery phase – with clear price trajectories (based on the social cost of carbon) – can provide forward guidance to investors, without immediately burdening businesses with new taxes (Van Dender and Teusch, 2020). This will lower uncertainty and help fill the green investment gap (Section: The Green Transition adds restructuring challenges) given that higher environmental policy uncertainty (e.g. arising from frequent policy reversals) significantly dampens investment, especially amongst capital-intensive firms (Dechezleprêtre, Kruse and Berestycki, 2021). Clear and certain price trajectories – coupled with the phasing out of fossil fuel subsidies and tax expenditures – promise significant emission reductions, while maintaining economic growth in the recovery. Increases of carbon tax are among the top reform priorities in the Czech Republic, Denmark, Ireland, Iceland and South Africa.

Stronger environmental policies do not necessarily hinder aggregate productivity growth. Productive firms facing stricter environmental policies can capitalise on new opportunities to raise revenues (e.g. via new and expanding markets or satisfying demand for greener goods) and reduce costs (e.g. via technological spillovers and lower borrowing costs) (Dechezleprêtre et al., 2019). By contrast, stringent environmental policy can force the downsizing/exit of less productive firms – by disproportionately raising their costs (Albrizio, Kozluk and Zipperer, 2017) – which creates space for productive firms to expand (Dechezleprêtre, Nachtigall and Stadler, 2020), thus boosting aggregate productivity.

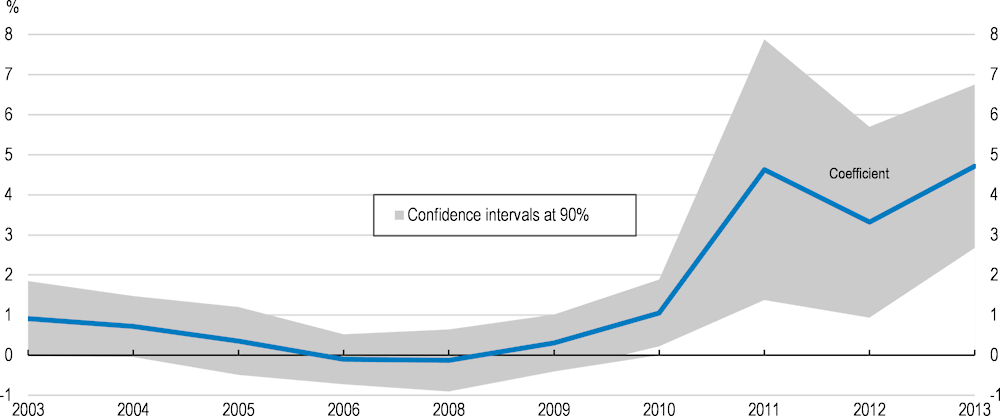

Figure 1.8. Most countries under-price their carbon emissions

Carbon pricing score,¹ 2018

1. The carbon pricing score (1- carbon pricing gap) shows how close countries are to pricing carbon in line with carbon costs. EUR 60 is a midpoint estimate for carbon costs in 2020, a low-end estimate for 2030. Pricing all emissions at least at EUR 60 in 2020 shows that a country is on a good track to reach the goals of the Paris Agreement to decarbonise by mid-century economically.

Source: OECD, Effective Carbon Rates 2021 Database.

Strong environmental policies would align firms’ incentives with the collective interest of environmental sustainability. The experience of the GFC shows that green recovery packages alone are insufficient to provide sustained incentives for green investment – notably, carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies – as they did not benefit from a clear commitment to long-term carbon pricing trajectories that can render such investments more viable (OECD, 2020f). Thus, emissions recovered quickly after an initial dip and green stimulus measures were overshadowed by a polluting recovery.

Beyond establishing effective environmental policy signals, policymakers should be mindful of four considerations as they attempt to engineer a green recovery and transition over the longer term: i) the impacts of policy decisions on reallocation; ii) the importance of complementary policies; iii) minimising cross-border leakage; and iv) the need to design policy packages to ensure their public acceptability.

Designing environmental policies with reallocation in mind

Since investment cycles can last several decades, macroeconomic stimulus packages need to be carefully designed to ensure they do not excessively subsidise polluting activities or lock-in carbon-intensive technologies. In this regard, the GFC provides a cautionary tale. Whereas the prevalence and resources sunk in zombie firms increased after 2007 (Adalet McGowan, Andrews and Millot, 2018), this phenomenon was more pronounced in heavily polluting industries (Figure 1.9). This suggests that the GFC and related policy response may have inadvertently slowed restructuring in polluting industries. This increased “high emission” zombie congestion can hinder necessary reallocation: i) between firms, if zombie firms crowd-out growth opportunities for innovative firms; and ii) within firms, if cash-strapped zombie firms are not able to respond to environmental policy signals and invest in low-emission technologies.

Some environmental policies are more reallocation-friendly than others. For example, tighter market-based Environmental Policy Stringency (EPS) is associated with stronger patterns of capital reallocation to innovative firms (Figure 1.7, Panel B). This is consistent with the idea that market-based policies achieve the largest emission reductions where it is the cheapest to abate them, without prior knowledge of the firms’ cost structure, and can be geared towards minimising administrative costs and maintaining competition (Albrizio, Kozluk and Zipperer, 2017).

Non-market based environmental policies (e.g. standards) are associated with weaker reallocation to innovative firms (Figure 1.7). But this may partly reflect the tendency for non-market tools to explicitly differentiate on plant vintage or provide a more favourable treatment to existing installations based on prior use (“grandfathering”). Vintage differentiated regulations may be necessary to garner policy support but to the extent older plants and installation are associated with incumbent firms they can impede market rejuvenation, as evidence from the coal-fired power plant industry suggests (Coysh et al., 2020).

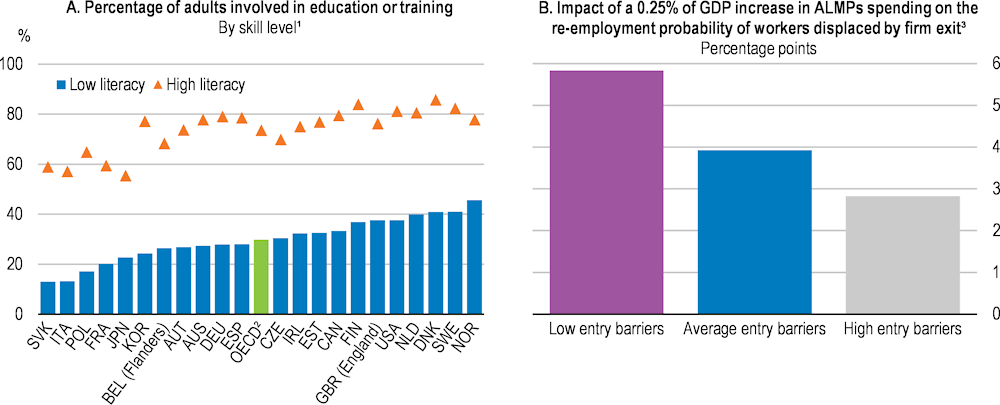

Figure 1.9. In emission-intensive industries zombie congestion rose more after the Global Financial Crisis

Share of capital stock sunk in zombie firms in emission-intensive versus other industries¹

1. After the Global Financial Crisis, the share of capital in zombie firms grew proportionally more in emission intensive industries. By 2013, one standard deviation in emission intensity is associated with an increase in the zombie capital share rising by 5 percentage points, relative to an average share of 12% of capital in zombie firms in that year. Annual estimates are obtained from regressing the share of capital in zombie firms on industry-level demand-embedded emission intensity for 9 European countries. In a year, one standard deviation in emission intensity is associated with an industry-level change in the share of capital in zombie firms equal to a dot; the lines are confidence intervals at 90%. The regression includes years and country fixed effects. The emissions are those of 2015 to avoid simultaneity problems. Three-way clustered standard errors (country, industry, and year).

Source: OECD calculations based on Adalet McGowan et al. (2018).

Complementary structural policies to support the Green Transition

The Green Transition also requires policies to rectify market imperfections that impede the flow of finance, knowledge and skills to green firms. For example, there is an urgent need to update financial market architecture (Box 1.2), given that firms subject to financial constraints after the GFC had higher emission intensities (Figure 1.9 and IMF, 2020a). There is also a case for policy support to green R&D (Box 1.2) through a combination of: i) “Technology-push” tools (e.g. direct subsidies, tax credits, project grants and loans) directed at technologies with the largest potential for emissions reduction that are furthest from the market (i.e. CCS, batteries for intermittent energy sources, and smart grids); and ii) “Market-pull” tools (i.e. tariff incentives, renewable portfolio standards), which can increase demand for green goods and thus spur green innovation. But the effectiveness of innovation policy support is enhanced when skilled labour is more readily reallocated to productive firms, given that the supply of researchers is fixed in the short-run (Acemoglu et al., 2018). Given partial transferability of skills between green and brown activities (Section: The Green Transition adds restructuring challenges), structural policies – which can reduce skill mismatch (Section: Removing obstacles to reallocation) – can help reallocate scarce skills to green firms. This is relevant at the current juncture, as skill mismatches reduced the gains – especially in the short run – from green stimulus measures during the GFC (Popp et al., 2020).

Box 1.2. Addressing imperfections in financial and knowledge markets

Investors are progressively reinforcing their positions on ESG (Environmental, social and corporate governance) assets but financial market imperfections still place the financing of green projects at a disadvantage. There is potential to reduce the information asymmetries and level the playing field by: i) specialising the informational and disclosure tools on sustainability (i.e. establish standards for how firms disclose and report environmental information to stakeholders), which can spur divestments into carbon-intensive firms (Mésonnier and Nguyen, 2021); ii) favouring the adoption of standards in project financing and banking operations; iii) providing a favourable regulatory and institutional environment for new financing products (e.g. green bonds), benchmark indexes that track environmental performances, and specialised investment vehicles (e.g. responsible investment funds) (OECD, 2015c); and iv) mainstreaming of climate considerations in central banking operations (e.g. portfolio management).

Even if the pollution externality is addressed, policy support for green R&D is warranted to address under-investment in R&D caused by knowledge spillovers. Green R&D is further disadvantaged by path-dependencies in fossil fuels use but policy support can help break this lock-in and then be phased-out as green technologies become profitable (Acemoglu et al., 2012). It can also decrease abatement costs and liberate firms’ resources for productive purposes while stable public R&D subsidies can spur green patenting, especially when coupled with strong environmental policies (Aghion et al., 2016).

Preventing cross-border leakage of emissions

Emission leakage – whereby stringent domestic climate policies push production (and thus emissions) to more permissive jurisdictions – is a key challenge, as environmental policy stringency rises against a backdrop of mobile production in the global value chain. Emission leakage reduces the effectiveness of climate mitigation policies (as emissions are displaced rather than cut) and weakens political support for the implementation of climate policies, if foregone production implies fewer jobs and less fiscal revenues. Compensating firms in emission-intensive trade-exposed industries to retain their domestic production does not align with the “polluter-pays” principle and can result in substantial overcompensation (D’Arcangelo, 2020). By contrast, Border Carbon Adjustments – a measure to address carbon-leakage and competitive advantage concerns through pricing the carbon embedded in imports – could be a less distortive tool to address leakage. But their implementation could result in trade and environmental tensions if perceived as tools for ‘green protectionism’. As such, Border Carbon Adjustments require careful design, including a review of their compatibility with trade agreements; types of emissions covered; estimation of carbon content; and the status of export rebates (OECD, 2020t).5 In any case, global co-ordination on climate mitigation policies is the most cost-efficient solution (Chapter 2).

Public acceptability will determine the success of Green Transition policies

The implementation of environmental policies to steer the Green Transition hinges upon their public acceptability (Coglianese, Finkel and Carrigan, 2013), as exemplified by significant policy reversals in Australia (the repeal of a carbon permits system, Clean Energy Act 2011) and the United States (the signing, subsequent withdrawal and recent re-joining of the 2015 Paris Agreement). While most people care about the environment, environmental policies – particularly market-based policies (e.g. carbon taxes) – can raise concerns about the consequences for job security and the cost of living.

These fears are not completely unfounded. While the Green Transition entails net-positive health and economic effects (Vona, 2019), it implies fundamental restructuring from which transition costs arise:

Major direct impacts on specific sectors, such as mining and fossil fuel and energy-intensive industries (Chateau, Bibas and Lanzi, 2018) through competitiveness losses due to higher costs – particularly in the case of unilateral actions or potentially direct phasing out of activity due to bans on specific inputs and outputs.

Income loss of some workers in pollution-intensive industries, as well as through knock-on effects in sectors heavily reliant on activity in these sectors, driven by both non-employment and lower-income in future employment (Walker, 2011).

Low-skilled workers are particularly affected, especially if their competencies are automated or offshored, and poorly matched to the skill requirements of new green jobs (Marin and Vona, 2019).

Increases in relative prices of electricity and heating, which tend to constitute a larger share of spending for lower-income households (Levinson, 2019).

When the burden falls heavily on vulnerable groups, the policies’ fairness – a stronger acceptability determinant than their assessed effectiveness (Clayton, 2018) – will be perceived poorly by the public (Douenne and Fabre, 2020). These attitudes may be reinforced in the context of the global debate on to what extent advanced economies should carry more responsibility for climate change (CSO Equity Review, 2019). Capitalising on these perceptions, some pollution-intensive firms may seek to advance “job-killing” arguments against green policies or to exert direct political pressure on policymakers, especially if their assets would become stranded under the new regime (Deng, Wu and Xu, 2020). All this implies that ramping up environmental policies faces resistance, but several design aspects of environmental policy reform have been identified as helpful in securing public support (Box 1.3).

Box 1.3. Strategies for garnering public support for environmental policies

Mechanisms to counter the distributional effects of environmental policies are crucial for their acceptability. Taking the case of carbon pricing, while there is no silver bullet, public support for carbon pricing can be enhanced by:

Phased-in, transparent policy stringency increases (e.g. gradual carbon price increases), which provides households with adequate certainty to plan their due adjustments (Coady, Parry and Shang, 2018). A notable example is the Pan-Canadian Framework (PCF), which has introduced annual carbon pricing increments since 2019 and will reach its full capacity in 2022.

Revenue recycling to finance universal transfer payments, lower (income and labour) taxes and targeted support for affected communities (Coady, Parry and Shang, 2018). Effective implementation can be aided by efforts to: i) reduce existing inefficiencies in the tax system, which would also promote the novel taxation’s image of equity and efficiency (Klenert and Mattauch, 2019); and ii) make visible the immediate benefits the scheme delivers to households (Klenert et al., 2018).

Transparent revenue use, perceived as equitable and efficient. Progressivity is key: targeted transfers to exposed households are most effective, followed by universal lump-sum transfers. Cuts to labour taxes have mixed distributional consequences and capital or corporate taxes are more regressive (Klenert et al., 2018).

Revenue earmarking to environmentally-related measures (Hsu, Walters and Purgas, 2008), such as green R&D support, targeted fiscal incentives (e.g. capital grants), public infrastructure investments to address externalities and regulation of knowledge spillovers via renewable generation shares. An example is Europe’s Common Agricultural Policy, which aims to create a stronger link between direct support for farmers and their environmental footprint.

Public communication and education campaigns to emphasize the benefits of carbon pricing and correct public misperceptions, as support for green policies increases with climate change knowledge and the belief of human causation (Sibley and Kurz, 2013). They should also highlight that climate change will especially harm the poor without policy action (Leichenko and Silva, 2014) – demonstrating that climate mitigation policies have the benefit of providing revenues to offset such effects – and engage the local business community to garner its support or soften its opposition (Chu, Wu and Van den Broeck, 2014).

Non-aversive policy naming and branding. Avoiding wording that implies taxation (e.g. the Swiss labelling of the “CO2 Levy”) can avoid evoking general distrust in government and its capacity to spend the revenues for the common good (Klenert et al., 2018).

Promoting actions that increase trust in the local political and government institutions, as that is associated with higher support for environmental policies (Harring and Jagers, 2013).

Policies to support people in recovery and transitions

As the recovery gains momentum, a key challenge will be to gradually withdraw support and allow resources to be reallocated. Reallocation creates opportunities, but can come at a cost, especially for the less skilled and those already on the margins of the labour market. In order to convert these challenges into opportunities, people need the right skills, income support during the transition and protection for vulnerable populations.

Turning passive support into activation and coping with creative destruction

With a high share of workers protected by job support schemes, a comprehensive exit strategy will be needed, that should include a requirement for workers to register with the public employment services (and benefit from job search assistance, career guidance and training can support transitions from unviable to viable jobs). To underpin a swift recovery, policy should shift away from broad support to firms and workers towards more targeted measures (Box 1.4). Early interventions – especially prior to job displacement – can be very effective in this regard (OECD, 2018c).

Box 1.4. Job retention schemes – reforming popular emergency tool to support recovery

By May 2020, job retention schemes (JRS) supported about 50 million jobs across the OECD – about ten times as many as during the GFC. These schemes typically allow firms to adjust working hours at zero costs, greatly reducing the number of jobs at risk of termination due to liquidity constraints. While intended to temporarily maintain employer-employee links during the pandemic, JRS may become a permanent institutional feature of labour markets.

To support the recovery, JRS need to be re-designed to: i) align replacement rates with those of unemployment benefit schemes (currently not the case in many countries); and ii) ensure that their interaction with income support benefits does not undermine work incentives and reinforced inequalities. Well-designed JRS should give employers incentives to use them only as an emergency tool while containing adequate incentives for workers to search for jobs. This can be achieved by:

Requiring firms to contribute to the costs of hours not worked or increasing the employer contribution over time, so that JRS only subsidises job matches that the firm deems viable.

Limiting the job retention support in time, while allowing some flexibility regarding the health and economic conditions.

Registering beneficiaries of the JRS with public employment services (PES) and making them available to be hired. This allows workers to benefit from job-search assistance, career guidance and training and encourages mobility towards viable jobs. Early, targeted interventions to encourage labour mobility are efficient (Andrews and Saia, 2017).

Promoting training for workers on reduced working hours to improve the viability of their current job or improve the prospect of finding a new one.

Easing restrictions on combining income from JRS with income from other jobs to incentivise workers to seize new job opportunities.

Source: Blanchard, Philippon and Pisani-Ferry (2020); OECD (2020a), OECD (2020n).

Protecting low-income workers