Based on 2021 Country Notes, this chapter highlights four key areas of structural reforms that necessitate international co-operation: health, climate change, trade and the taxation challenge of the digital economy. While many issues in these areas can and should be addressed through domestic policies in concerned countries, cross-border spill-overs motivate the need for international co-operation. Close co-operation and policy co-ordination can address the significant international public good element more efficiently, delivering on the objective of stronger, more resilient, sustainable and equitable growth.

Economic Policy Reforms 2021

2. Priorities for international co-operation: Reform areas with cross-border effects

Abstract

Health: Improving international collaboration

The COVID‑19 pandemic highlighted the need for international co-operation on preparedness and resilience of health care systems to similar events around the world and on global health priorities. While countries need to act to improve their domestic health systems, international co-operation can help contain the spread of future pandemics and co-ordinate responses, including through the roll-out of vaccinations – boosting overall economic resilience and curbing potential trade-offs with economic growth. COVID-19 weaknesses in the international supply of essential health goods, including medicines, personal protective equipment and other medical devices were exposed. Currently, manufacturing and distribution capacities are limiting effective global pandemic response.

No single country produces all the goods it needs to fight a pandemic – including vaccines - and there is a high degree of interdependence in trade for these products. Underlying and compounding weaknesses in international supply chains was a lack of coherent, comparable and timely data that could be linked and shared across sectors, regions and countries. The crisis confirmed that health systems lag in terms of a harmonised approach to data governance and global standards for health data terminology and exchange. A unified response informed by data was thus impossible.

Another exposed weakness was the global shortage of health workers. As countries seek to strengthen their own health workforce, many will see international recruitment as the quickest way to increase capacity, but such recruitment should respect the WHO Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel (WHO, 2010).

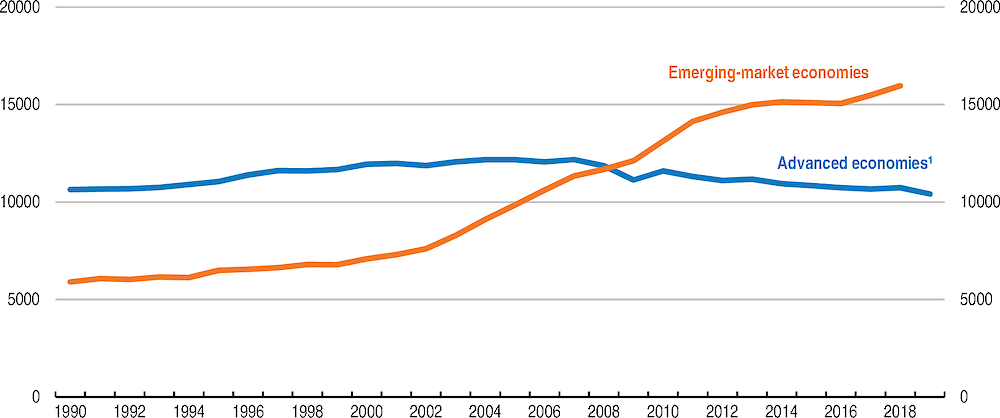

Efforts to develop and make accessible COVID-19 vaccines benefit already from considerable international co-operation in research and development (Figure 2.1), information exchange and harmonisation of clinical trial design. Importantly, closer co-operation on issues concerning manufacturing and distribution capacity, allocating supplies and planning vaccination campaigns can help secure equitable and affordable access for all. Ensuring that intellectual property protection and insufficient know-how and technology transfer do not become a barrier are also important. Many of these mechanisms can present valuable lessons in preparing for future crises.

As flagged already prior to the pandemic, there is a risk of global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) (OECD, 2018). Millions of people are infected each year by microbes susceptible to the development of resistance. Resistant microbes double the probability of developing a complication and triple the risk of death compared to non-resistant forms. The development of resistance by microbes causing, among others, tuberculosis, HIV and hospital infections imposes the main brunt of this problem on low- and middle-income countries. Every country, regardless of its economic situation, the strength of its health system or the level of antibiotic consumption, will face disastrous consequences if the spread of AMR is not contained. The issue is already partly addressed by the G20 but with limited success so far.

Figure 2.1. International scientific collaboration on COVID-19 biomedical research

Note: Economies are assigned to clusters based on their interconnection. The colour of an item is determined by the cluster to which it belongs. The higher the weight of an item, the larger its label and circle. Lines between items represent co-authorship links. In general, the closer two economies are located to each other, the stronger their relatedness. The strongest co-authorship links between economies are also represented by lines. Note that the territory attribution for these indicators is entirely based on country affiliation information reported by the authors and publishers as registered on PubMed. Please refer to https://doi.org/10.1787/888934223099 for more methodological information.

Source: OECD and OCTS-OEI calculations, based on U.S. National Institutes of Health PubMed data, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed 30 November 2020).

Table 2.1. Policy recommendations on international collaboration on health

|

Recent measures |

Recommendations |

|---|---|

|

☑There has been extensive international collaboration in vaccine R&D. In particular the ‘Access to COVID-19 Tools Accelerator’ (ACT) launched by the G20 brings together governments, health organisations, scientists, businesses, civil society and philanthropists to accelerate the development, production, and equitable access to COVID-19 tests, treatments, and vaccines. In this framework, over 50 diagnostic tests have been evaluated and 120 million affordable quality rapid tests are pledged for low and middle-income countries. ☑Over 1,700 clinical trials are being analysed for promising treatments and dexamethasone sufficient for up to 2.9 million patients in low-income countries has been secured. ☑ The vaccines pillar of ACT, COVAX is a global facility for speeding up vaccines development, securing manufacturing capacity and procurement, in which over 180 countries are engaged. |

Enhance international co-operation in securing and maintaining supply chains for essential medical products (including medicines and medical devices) as well as the capacity and utilisation of medical supplies and infrastructure. Security of supply could be enhanced, for example by: avoiding export restrictions, establishing new reporting and monitoring mechanisms that improve information on supply chain structures and capacities, reporting of product shortages consistently across countries, and exploring policies to address barriers to supplier diversification; formulating flexibilities and requirements for suppliers to mitigate supply chain risks; defining emergency procedures for procurement during public health crises; broadening, deepening existing joint procurement mechanisms and/or establishing new schemes. Improve the use of granular and timely data across borders (e.g. from electronic health records) for pandemic alert systems, identifying populations at risk and managing affected patients. To achieve this, enhance international coordination on harmonized approaches to data governance and global standards to ensure data privacy and security are protected while not impeding monitoring and research, as detailed in the OECD Council Recommendation on Health Data Governance. Use so-called pull mechanisms, such as genuine and large international Advance Market Commitments (AMC), to complement push mechanisms to fund R&D. One of the appeals of these mechanisms, that reward successful completion of R&D and reduce uncertainty around returns to investment, is that they can specify upfront conditions for procurement, licensing of intellectual property rights (IPRs) and affordability or access. Define upfront procurement schemes for vaccines and medical equipment based on international co-operation, identifying criteria for allocating product volumes to countries that are not based on ability to pay. Support international efforts to ensure that IPRs do not become barriers to transfer of know-how and building of production capacity for medicines and medical devices. This can be done through commitments to use existing mechanisms to make IP available at low or no cost, and to pool IP and encourage sharing of know-how. Increase international co-ordination to ensure that clinical trials are well-designed, adhere to rigorous methodological standards and are sufficiently powered to yield conclusive results. |

Climate change: Towards net-zero greenhouse gas emissions

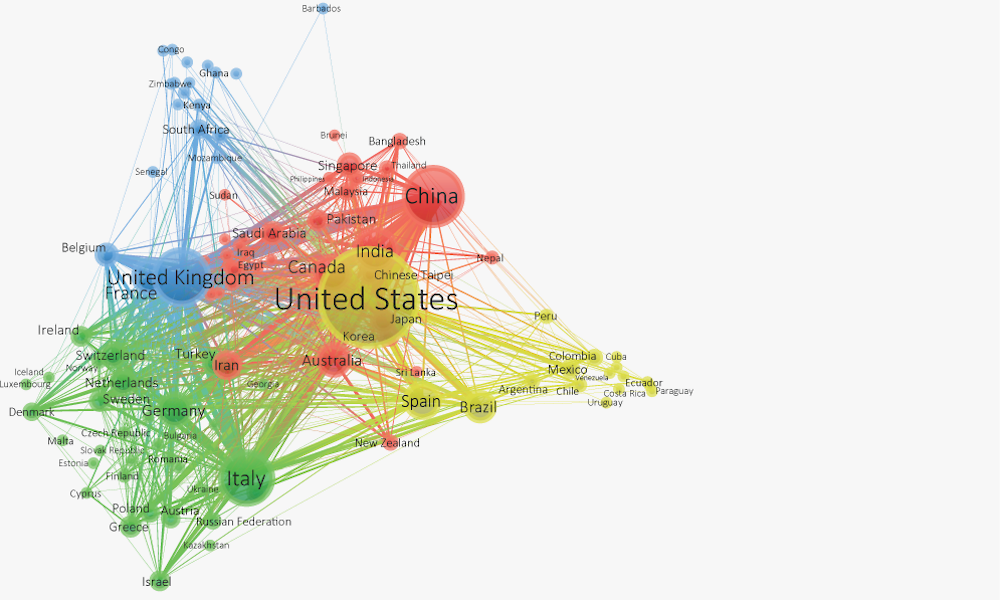

COVID-19 has put a dent in greenhouse gas emission trajectories, but past experience shows that economic recoveries have been associated with recoveries in emissions. Prior to the crisis, production-based emissions have continued increasing in emerging-market economies while falling only very slowly in advanced economies (Figure 2.2). Significant actions are required as part of stimulus and recovery packages to achieve a fall in emissions as economies recover.

Achieving the Paris climate change targets is estimated to require reaching zero net emissions globally in the second half of the 21st century, and even by 2050 to achieve the more ambitious interpretation of those targets. An increasing number of countries have pledged to meet such targets individually, but in most cases concrete actions on policies are yet to follow.

Currently, most emissions are priced too low or not priced at all (OECD, 2021). Moreover, fossil-fuel subsidies persist, further incentivising emission-intensive consumption, production and investment. This increases the risk of stranding assets and hence increasing the costs of the future transition. Progress in individual countries is welcome, but a cost-efficient approach to climate change requires closer global co-operation. For example, more cross-border co-operation on climate policies, including carbon pricing, would help mitigate leakage, allow emission reductions at a lower cost and improve access to and development of low-emission technologies. Such cooperation has the potential to boost economic growth and make the transition less costly. International policies to build resilience to the inevitable impacts of climate change are also important, alongside emissions reduction.

Figure 2.2. Globally, emissions continued to rise prior to the COVID-19 crisis

CO2 emissions from fuel combustion, Mt of CO2

Table 2.2. Policy recommendations on mitigating climate change

|

Recent measures |

Recommendations |

|---|---|

|

☑ More than half of OECD and several key non-member countries have adopted or announced long-term carbon neutrality objectives, with various interim targets, levels of detail and coverage. Details of the commitments differ and plans on how to achieve the targets have yet to be developed. ☑ In 2018 and 2019, the UN Conference of Parties (COP) made some progress towards the implementation of the 2015 Paris Agreement to mitigate and adapt to climate change, in particular by agreeing on rules on how to measure and report on emission-cutting efforts. ☑ An increasing number of OECD and non-member countries have introduced some kind of carbon pricing mechanism or strengthened existing mechanisms. ☑ Since 2016, as part of a G20 process China, the United States, Mexico, Germany, Indonesia, Italy, Argentina, Canada, France and India have undergone or signalled their intent to pursue peer reviewing of their fossil fuel subsidies. |

Prior to COP26 in 2021, adopt and update both near-term commitments (NDCs) and long-term national low carbon strategies in line with the international COP 21 goals. The strategies need to cover all emitting sectors and make broad use of available policy tools, in particular carbon pricing. Lay out credible action plans on how national decarbonisation strategies will be implemented, taking into account international spillovers (e.g. carbon leakage) and identifying areas for potential co-operation. Use transparent cost and benefit evaluation mechanisms in the selection and timing of different policy tools and identification of possible interactions, bottlenecks and effects on business performance and household wellbeing. Identify opportunities for high-return government support to facilitate and incentivise low-carbon investment (including in infrastructure) and innovation. To the extent possible, co-ordinate the decarbonisation strategies and implementation with other countries to achieve global targets at minimum cost and minimise leakage and competitiveness concerns. Commit to introducing and progressively ramping up carbon pricing once the recovery is underway. In particular, prioritise the phase-out of fossil-fuel subsidies and incentives for carbon-intensive investment and consumption to reallocate resources to low-carbon investment and innovation, including R&D. |

International trade: International rules-based trading system fit to restore confidence and support global trade

During the COVID-19 crisis trade and global value chains (GVCs) have shown remarkable resilience and proven essential to reacting to the enormous increases and shifts in demand for certain goods, in particular medical goods. Countries have recognised this important role. Despite an initial surge in mostly temporary export restrictions countries have implemented numerous measures to facilitate trade and streamline border and customs procedures to ensure the flow of goods despite stringent health measures. Moreover1, several large trade agreements were signed between 2019 and 2021.

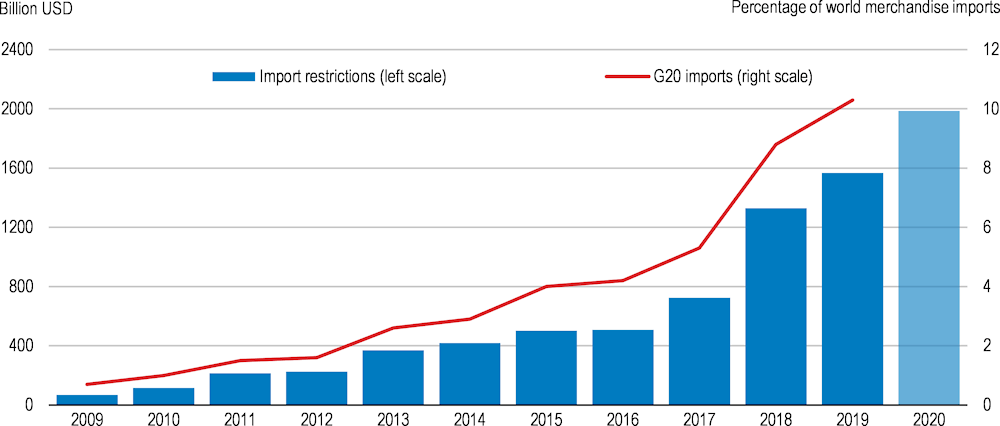

Over time, trade has helped lift more than a billion people out of poverty and trade openness gives firms access to larger markets, world class inputs and new technologies, encouraging competition, productivity and innovation. It gives consumers greater access to goods and services at a lower price. Yet, trade policy was facing significant headwinds prior to the pandemic already, with countries increasingly concerned about an uneven international playing field; about finding a foothold in digital markets characterised by first mover advantage and winner-takes-most dynamics; and about being cut out of input and output markets by rising trade tensions and unilateral trade measures. Concerns over temporary shortages in certain goods at the height of the pandemic have given rise to increasing calls for governments to do more to ensure the resilience of GVCs for essential goods. Some governments are also calling for greater regionalisation of GVCs or for a reshoring of production of certain goods, adding to a trend of businesses shortening their global value chains and trade policies in merchandise as well as services becoming more restrictive (Figure 2.3).

Behind some of these tensions are concerns that the international rulebook has not kept pace with economic and technological changes, and that not everyone is playing by the existing rules. Furthermore, the resolution of trade disputes at the WTO came under threat when the WTO Appellate Body lost quorum in 2019. As policy makers begin to build back better, resilience to future shocks is a key objective. The pandemic has shown the interdependence of our economies and the reliance on global markets and supply chains to absorb and react to shocks and to generate the economies of scale necessary to satisfy the global demand for essential goods. Policy coherence, transparency and information sharing on market conditions and policies are key ingredients in keeping trade flowing and helping firms manage the risks along their value chains in a predictable policy environment. In the short-term, there is a need to facilitate not only the trade in goods but also in services.

Figure 2.3. COVID-19 has exacerbated a trend towards more restrictive trade policies

Cumulative import-restrictive measures in G20 economies¹

1. The cumulative trade coverage estimated is based on information available in the Trade Monitoring Database (TMDB) on import measures recorded since 2009 and considered to have a trade-restrictive effect. The estimates include import measures for which HS codes were available. The figures do not include trade remedy measures. COVID-19 trade and trade-related measures are not included. The import values were sourced from the UNSD Comtrade database. 2020 estimates only cover restrictions up to June 2020.

Source: World Trade Organisation.

Table 2.3. Policy recommendations on international trade

|

Recent measures |

Recommendations |

|---|---|

|

☑ Several significant free trade agreements were concluded, including: the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership between ASEAN and Australia, China, Japan, Korea and New Zealand; .the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership-CPTPP, comprising inter alia Australia, Canada, Japan and Mexico; United States Mexico Canada Agreement; the EU-Japan Economic Partnership agreement; the African Continental Free Trade Agreement, the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement between Canada and the EU; and the EU-Japan FTA. ☑ The WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement, concluded in Bali in 2013 and aimed at reducing the costs and time needed to export and import goods, entered into force in 2017. ☑ Trade facilitation measures proved instrumental in addressing constraints at border crossings due to health measures. |

Reinforce commitment to rules-based trade, including by ensuring implementation and enforcement of existing trade rules, increasing policy transparency, and working towards effective trade dispute resolution. Tackle gaps in the existing rulebook, for instance with respect to government support that distorts markets and harms the environment, and agree new rules to address emerging issues such as state capitalism and the digital transformations of our economies. Facilitate trade in goods and services through full implementation of the WTO Trade Facilitation Agreement, trade-conducive domestic reforms, and renewed safe international travel. Make progress in international economic co-operation harnessing the full range of international economic co-operation tools, including legally binding rules, voluntary guidelines and codes, and transparency and dialogue. |

Taxation: Addressing the tax challenges of the digitalisation of the economy

Globalisation and digitalisation have highlighted weaknesses in the international corporate income taxation rules. This has led to growing dissatisfaction with the current rules and has seen a growing number of jurisdictions taking unilateral actions or departing from agreed international standards. There has also been an increase in tax disputes and tax uncertainty.

Such developments threaten the stability of the international tax system and represent a risk to global investment and growth. It is estimated that prior to the COVID-19 crisis base erosion and profit-shifting (BEPS) practices cost countries USD 100-240 billion in lost revenue annually, which is equivalent to 4-10% of the global corporate income tax revenue.

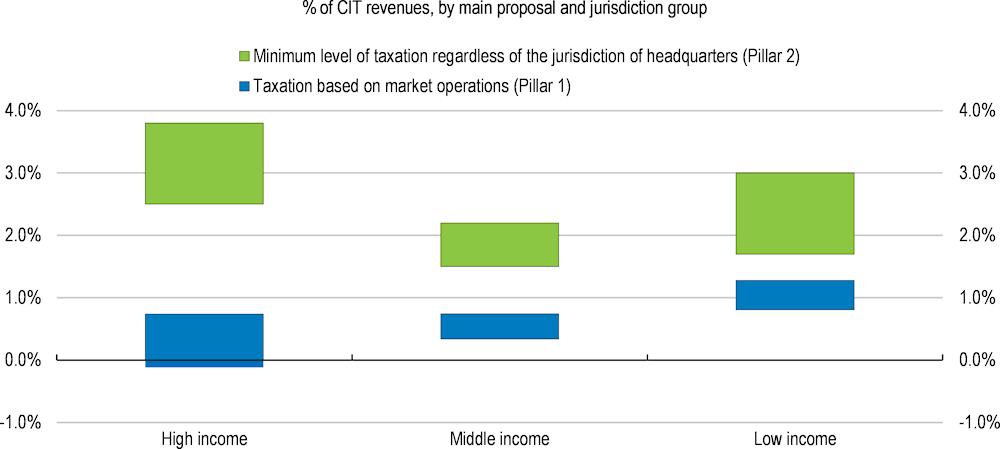

The OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework on Base Erosion and Profit Shifting brings together over 135 jurisdictions on an equal footing to collaborate on the ongoing implementation of the BEPS Package and addressing the tax challenges arising from the digitalisation of the economy. Efficient international co-operation in this area can help secure budgetary revenues and thereby helping to restore fiscal sustainability after the crisis, including through reducing the scope for tax competition and evasion.

Figure 2.4. Potential revenue gains from an international agreement on digital taxation of multinational enterprises

Percentage of CIT revenues, by main proposal and jurisdiction group

1. Estimates based on assumptions in OECD (2020), carried out for the Inclusive Framework on BEPS. Estimates are presented as ranges to reflect uncertainty around the underlying data and modelling. Groups of jurisdictions (high, middle and low income) are based on the World Bank classification. United States is not included in the panel of high income jurisdictions in the case of green bars, but is included in blue bar estimates. Investment hubs (defined as jurisdictions with a total inward FDI position above 150% of GDP) are excluded.

Source: OECD (2020), Tax Challenges Arising from Digitalisation – Economic Impact Assessment: Inclusive Framework on BEPS, OECD/G20 Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project.

Table 2.4. Policy recommendations on digital taxation

|

Recent measures |

Recommendations |

|---|---|

|

☑ The automatic exchange of financial account information that started in 2017 and 2018 has delivered the exchange of 47 million offshore bank accounts, with a total value of EUR 4.9 trillion. These results add to the over EUR 95 billion in additional revenue identified through investigations and voluntary compliance programmes and to the large decrease of bank deposits in international financial centres. ☑ The Inclusive Framework released Blueprint reports in October 2020, which describe detailed proposals to address tax challenges from the digitalisation of the economy. In October 2020, the G20 welcomed these reports and urged the Inclusive Framework to address the remaining issues with a view to reaching a global and consensus-based solution by mid-2021. |

Continue multilateral discussions to reach an international agreement. |

Bibliography

OECD (2018), Stemming the Superbug Tide: Just a Few Dollars More, OECD Health Policy Studies, OECD Publishing, Paris.

OECD (2021) Effective Carbon Rates 2021. Document accompanying the update of the effective carbon rates database. COM/ENV/EPOC/CTPA/CFA(2020)4/REV1

WHO (2010) https://www.who.int/hrh/migration/code/code_en.pdf?ua=1

Note

← 1. As of mid-October 2020, 84 (63%) of all G20 measures taken in response to the pandemic were trade facilitating, while 49 measures (37%) were trade restrictive (mostly export restrictions). A broader measure of OECD Trade Facilitation Indicators showed that by May 2020 new trade facilitating administrative measures outnumbered the new trade restricting border and customs measures.