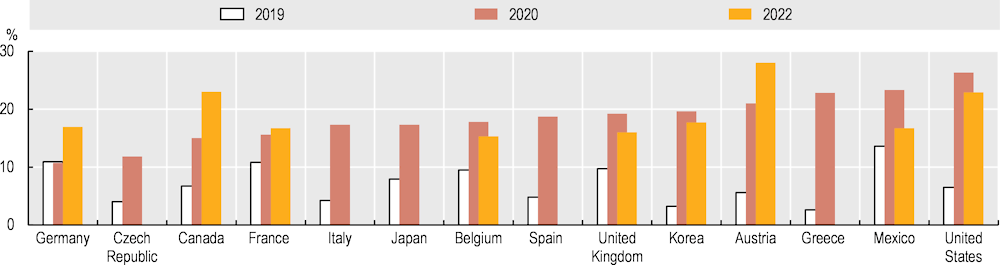

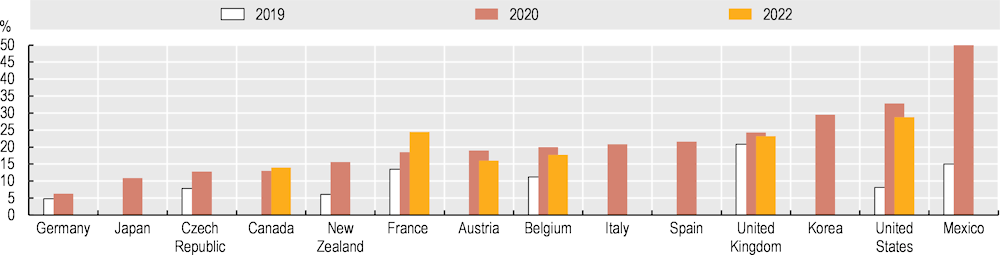

Good mental health is essential for healthy populations and economies: when people live with poor mental health, they have a harder time succeeding in school, being productive at work, and staying physically healthy (OECD, 2021[1]). The COVID‑19 pandemic seriously disrupted the way people live, work and learn, and fuelled significant increases in mental distress. At the start of the pandemic, the share of the population reporting symptoms of anxiety and depression increased in all OECD countries with available data, and as much as doubled in some countries (Figure 3.19 and Figure 3.20). OECD analysis has shown that population mental health went up and down over the course of the pandemic – typically worsening during periods when infection and death rates were high, or when stringent containment measures were in place. Available data point to some recovery in population mental health as the pandemic situation improved, but also suggest that mental ill-health remains elevated. In Belgium, Korea, the United Kingdom and the United States, data from 2022 typically show small decreases in the share of the population reporting symptoms of depression, compared to 2020. However, the prevalence for 2022 remains at least 20% higher than pre‑pandemic, and in some cases over double or triple the pre‑pandemic rate (Figure 3.19). Persistently high levels of mental distress “beyond” the pandemic could reflect the confluence of multiple crises: the cost-of-living crisis, climate crisis and geopolitical tensions.

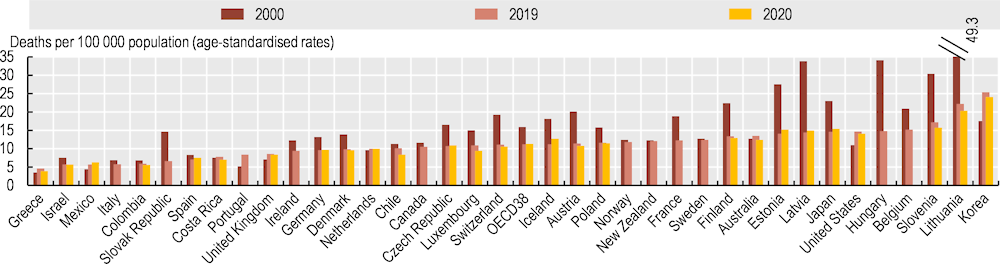

Shocks such as pandemics, severe weather events and financial crises can also heighten the risk of suicidal behaviour. While complex social and cultural factors affect suicidal behaviour, mental ill-health increases the risk of dying by suicide. Rates of death by suicide currently vary almost six‑fold across OECD countries, and are over three times higher for men than women. Deaths by suicide were generally trending downward prior to the pandemic, falling by 28.4% on average in the period between 2000 and 2019 (Figure 4.21). There were concerns that the COVID‑19 crisis would lead to more suicides, and significant increases in suicidal ideation have been observed in some countries, particularly among young people (OECD/European Union, 2022[2]). To some extent, these concerns were not realised in the first year of the pandemic: in the 27 OECD countries for which data are available, rates of death by suicide decreased by 2.4% on average between 2019 and 2020. However, this change varied across countries. In a third of countries with available data, suicides increased between 2019 and 2020 whereas for another third of the countries it decreased by 5% or more. Between 2019 and 2020 the rate of death by suicide respectively increased by 13.4% and 10.5% in Iceland and Mexico, and it decreased by 16.8% and 15.2% in Chile and Greece.

OECD countries took rapid action to step up mental health support in response to the pandemic. In a policy questionnaire in 2022, all 26 replying OECD countries reported having introduced emergency mental health services in response to the pandemic, and almost all (25 out of 26) reported that they had permanently increased mental health care support or capacity (OECD, 2023[3]). However, increases in capacity or support have not always been commensurate with need. This is not a new challenge, but one that has been exacerbated: even before the pandemic, two out of three people seeking mental health support reported difficulties in getting it (OECD, 2021[1]).