The COVID‑19 pandemic has shown the global impact of public health threats. As not all lessons from previous health crises such as the 2009 H1N1 flu pandemic were applied before the COVID‑19 pandemic, countries could learn vastly from this experience to be better prepared in the future. Recent OECD work has highlighted three major vulnerabilities that health systems faced during the pandemic – they were underprepared, understaffed, and suffered from underinvestment (OECD, 2023[1]). Addressing these vulnerabilities is critical to strengthening the resilience of health systems to future crises.

As more than three years have passed since the first cases and deaths due to infection from the SARS‑CoV‑2, it is possible to have a more complete picture of the impact and reach of the pandemic in terms of mortality. Across OECD countries, over 3.2 million people were reported to have died due to COVID‑19 between 2020 and 2022 – around 48% of the 6.7 million reported deaths worldwide. However, these mortality figures are underestimated due to differences in reporting among countries and, critically, wide differences in testing capacity and practices. Countries also decided in some cases to stop the regular reporting of COVID‑19 deaths in 2023 as the pandemic began to fade. As a result, the figures presented here cover the three‑year period from 2020 until the end of 2022.

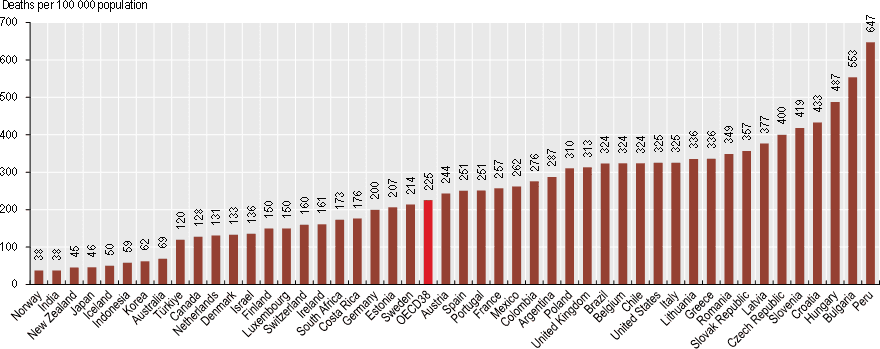

On average across OECD countries, 225 deaths per 100 000 population were reported during the period 2020‑22. Norway, New Zealand, Japan, Iceland, Korea and Australia had the lowest rates, at fewer than 70 reported COVID‑19 deaths per 100 000 population. In contrast, Hungary, Slovenia and the Czech Republic had 400 or more COVID‑19 deaths per 100 000 population. Reported COVID‑19 death rates were also relatively high among many OECD accession countries – notably Peru, Bulgaria and Croatia (Figure 3.9).

Looking ahead, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) – the ability of microbes to resist antimicrobial agents – is amongst the most pressing public health threats. It has the potential for significant health and economic disruption at a global scale. The drivers of AMR are complex, though heavy reliance on antimicrobials in human and animal health remain important contributing factors (OECD, 2023[2]).

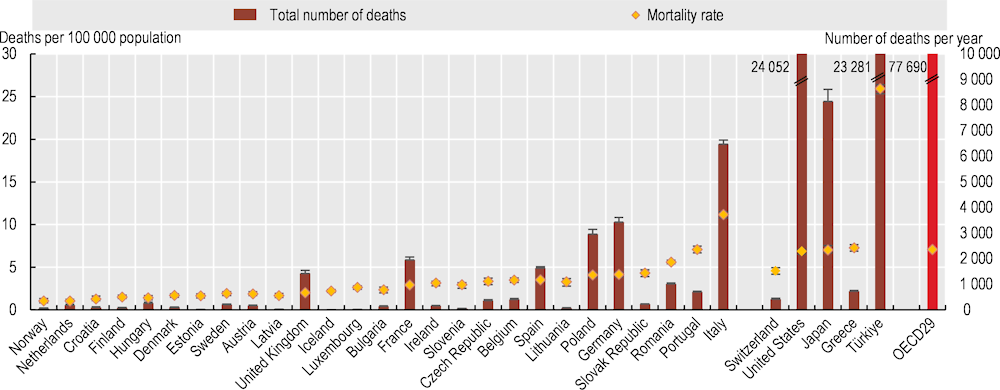

The latest OECD estimates suggest that every year, resistant infections claim the lives of nearly 79 000 people across the 29 OECD and 3 OECD accession countries included in the analysis (Figure 3.10). The annual AMR mortality rate is estimated to average 7.1 deaths per 100 000 population across the 29 OECD countries analysed. Across OECD countries, the expected average annual AMR mortality rate ranges from 7.3 to 25.9 deaths per 100 000 population, with Türkiye, Italy and Greece estimated to have the highest AMR mortality rates. Results also show that the annual cost of AMR to the health systems of the countries analysed is expected to average around USD PPP 28.9 billion up to 2050, corresponding to almost USD PPP 26 per capita. In addition, AMR leads to losses in labour market participation and productivity at work, with these losses expected to amount to nearly USD PPP 36.9 billion.

Countries can consider a wide range of cost-effective strategies to tackle AMR, in line with the One Health approach, a multidisciplinary and multi-sectoral approach that promotes co‑ordination and collaboration across human and animal health, agri-food systems and the environment to tackle threats to public health, including AMR. These include optimising the use of antimicrobials (see section on “Safe prescribing in primary care” in Chapter 6). Promoting environmental and hand hygiene practices in healthcare facilities are also highly cost-effective. Beyond human health, enhancing food handling practices and improving biosecurity in farms can yield considerable health and economic benefits.