The number of new nursing graduates is a key indicator to assess the number of new entrants to the nursing profession who might be available to replace retiring nurses and to respond to any current or future shortages. The number of nursing graduates in any given year reflects decisions made a few years earlier (about three years) related to student admissions, although graduation rates are also affected by student dropout rates.

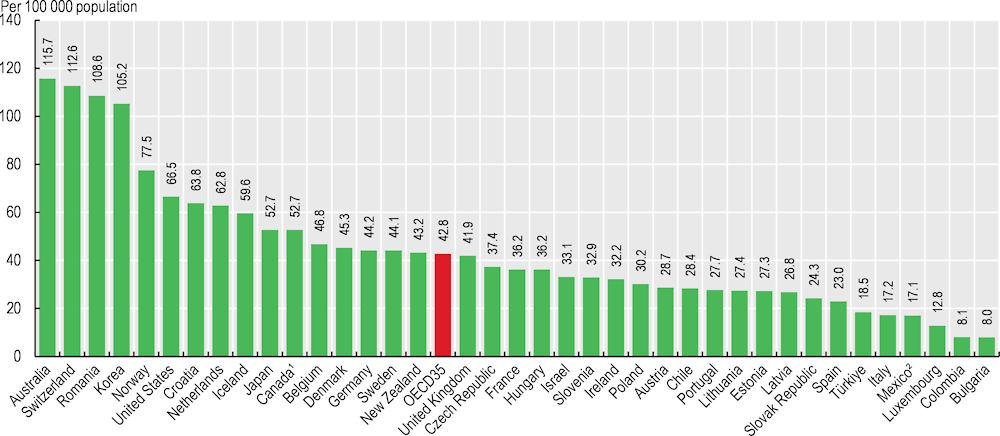

Overall, the number of nursing graduates across OECD countries increased from about 350 000 in 2000 to 520 000 in 2010 and 640 000 in 2021. In 2021, the number of new nursing graduates ranged from fewer than 20 per 100 000 population in Colombia, Luxembourg, Mexico, Italy and Türkiye to over 100 per 100 000 in Australia, Switzerland and Korea (Figure 8.22). The low numbers in Colombia, Mexico and Türkiye are related to the low numbers of nurses working in the health system (see section on “Nurses”). In Luxembourg, the low number of nursing graduates is offset by a large number of students from Luxembourg who get their nursing degree in a neighbouring country, as well as the capacity of the country to attract nurses from other countries through better pay and working conditions (see section on “Remuneration of nurses”).

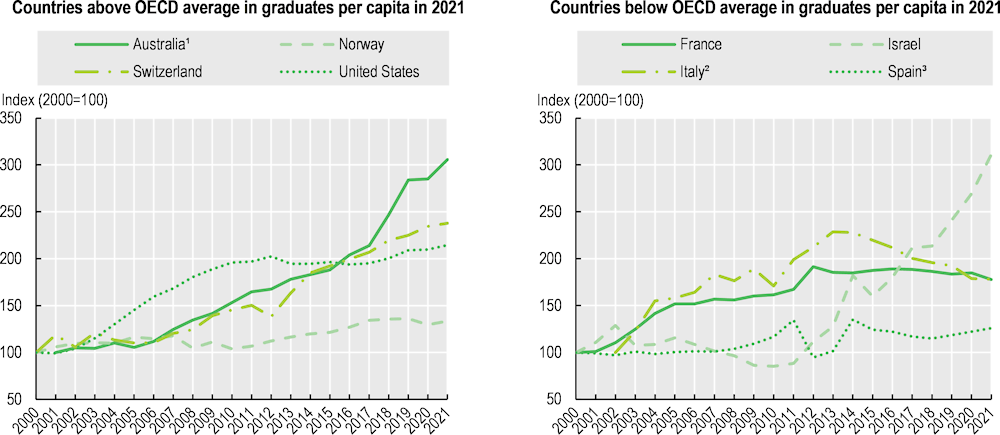

The number of new nursing graduates per 100 000 population has increased in all OECD countries since 2000, but with varying growth rates. In Italy, the number of nursing graduates increased fairly rapidly in the 2000s but has decreased since 2013 (Figure 8.23). However, following the pandemic, the number of applications to nursing education programmes has increased, along with the number of students admitted, which should lead to an increase in nursing graduates if these students complete their studies (OECD, 2023[1]). In Spain, the number of nursing graduates also fell in the years before the pandemic, but it started to increase at least slightly in 2020 and 2021. Following the pandemic, the number of applications to nursing programmes increased strongly in Spain (by over 50% between 2019 and 2021), but the number of students admitted in these programmes increased only marginally (by 6%) due to persistent capacity constraints (OECD, 2023[1]).

In the United States, the number of nursing graduates doubled between 2000 and 2010 (from around 100 000 in 2000 to 200 000 in 2010). This was followed by a period of stability, but the number has started to go up again in recent years. In Switzerland, the number of new graduates has increased greatly over the past 15 years, driven to a large extent by an increase in the number of graduates from “associate professional nurse” (or “intermediate care worker”) programmes. In Norway, the number of students admitted to and graduating from nursing education programmes has also increased over the past decade, but at a more moderate rate than in Switzerland. A persistent issue in Norway, as in other OECD countries, is retaining new nursing graduates in the profession. The number of new nursing graduates in Israel tripled between 2011 and 2021, but it remains below the OECD average relative to the country’s population.

One persistent challenge across OECD countries is the need to attract more male students to nursing. The general perception remains that nursing is “women’s work”, and that the occupation has a low professional status and autonomy, along with limited career progression opportunities (Mann and Denis, 2020[2]). In most countries, at least 80% of students applying and admitted to nursing programmes continue to be female, reflecting the traditional gender composition of the nursing workforce.