The level of remuneration of doctors is an important factor in the attractiveness of the medical profession, and how remuneration differs across categories can be a criterion in deciding whether to pursue a career in general practice or in one of the various medical specialities. Differences in remuneration levels of doctors across countries can also act as a “push” or “pull” factor when it comes to physician migration (OECD, 2019[1]). In many countries, governments can determine or influence the level and structure of physician remuneration by regulating their fees or by setting salaries when doctors are employed in the public sector.

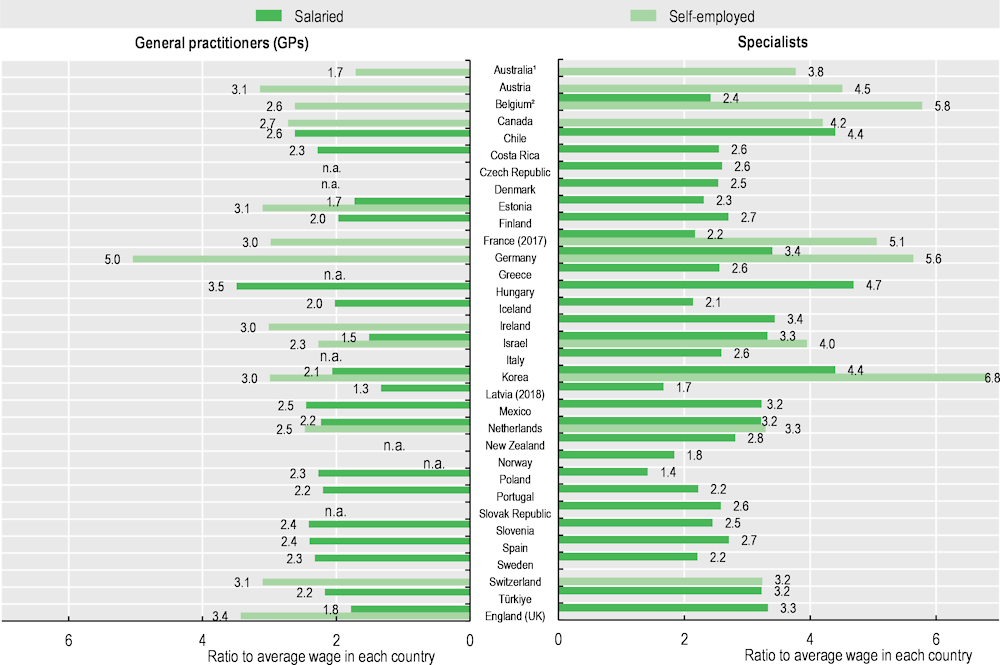

In all OECD countries, the remuneration of doctors (both GPs and specialists) is substantially higher than the average wage of a full-time employee across all economic sectors. In 2021, GPs generally earned between two and five times more than the average wage across OECD countries, while the income of specialists was at least twice, but in some cases up to six times, that of the average wage (Figure 8.11).

In most countries, specialists earned more than GPs. In Australia, Belgium and Korea, the income of self-employed specialists was at least double that of self-employed GPs. In Germany, the difference between self-employed specialists and self-employed GPs was much smaller, at about 12%.

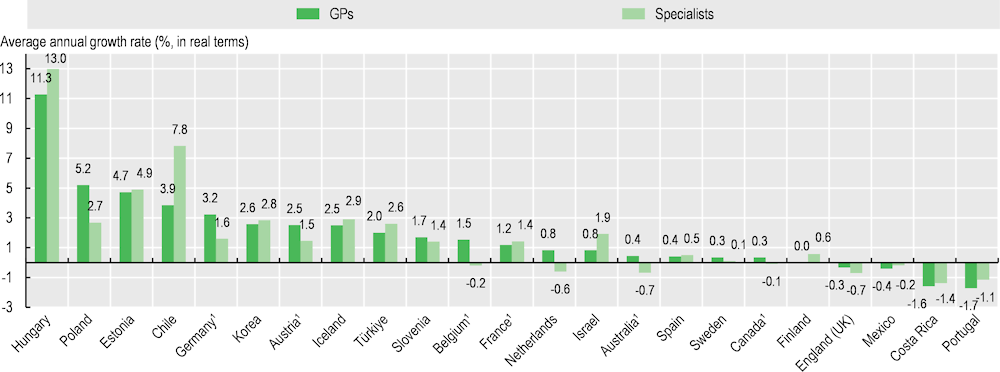

In most countries, the remuneration of physicians has increased since 2011 in real terms (adjusted for inflation), but growth rates differ across countries as well as between GPs and specialists (Figure 8.12). The pay increases for both specialists and generalists have been particularly strong in Hungary and Chile. In Hungary, the government has raised the remuneration of both specialists and generalists substantially over the past decade in an effort to reduce emigration of doctors and address domestic shortages. The large increases in Chile are mainly due to successive pay rises for specialists and generalists between 2012 and 2016.

In about half of countries, the remuneration of specialists has risen faster than that of generalists since 2011, thereby increasing the remuneration gap between the two professional categories. This has been the case in Chile, in particular, and to a lesser extent in Hungary and Israel. However, in Poland, Austria, Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands, the remuneration gap has narrowed, as the income of GPs has grown more than that of specialists.

In some countries, including Portugal, Costa Rica and the United Kingdom, the remuneration of both GPs and specialists fell in real terms between 2011 and 2021. In Portugal, a substantial reduction occurred between 2011 and 2012; since then, doctors’ income has increased again, but the income level in 2021 remained below that of 2011 when taking inflation into account. In the United Kingdom, the remuneration of doctors has fallen slightly in real terms over the past decade. This was also the case for nurses and other NHS staff (The Health Foundation, 2021[2]).

When comparing doctors’ income, it is important to bear in mind that the remuneration of different categories of surgical or medical specialties can vary widely within a country. In France, for example, surgeons, anaesthetists and radiologists made at least twice as much as paediatricians and psychiatrists in 2020 (DREES, 2022[3]). Similarly, in Canada, ophthalmologists and many surgical specialists had at least twice the income of paediatricians and psychiatrists in 2018/19 (CIHI, 2020[4]). In many countries, the remuneration of paediatricians is close to that of GPs, reflecting similarities in their practices.