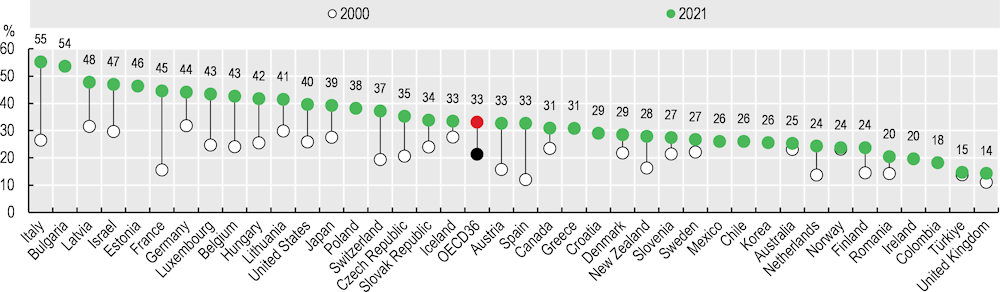

In 2021, one‑third of all doctors in OECD countries were over 55 years of age, up from just over one‑fifth in 2000 (Figure 8.6). The share of doctors over 55 increased between 2000 and 2021 in all countries for which data are available, although the share has stabilised in some countries, with the entry of many new young doctors into the profession in recent years, and the progressive retirement of the baby-boom generation of doctors.

Some countries have seen a rapid ageing of their medical workforce over the past two decades. Italy, where the share of doctors aged 55 and over more than doubled to reach 55% in 2021, is the most striking example. There has also been strong growth in the share of doctors aged 55 and over, and in the share of doctors aged 65 and over, in Latvia, Israel and France. No fewer than 25% of all doctors in Italy and Israel were aged 65 and over in 2021. In France, this proportion was 18% of all doctors in 2021 (more than one in six).

Ageing of the medical workforce is a concern, as doctors aged 55 and over can be expected to retire in the following decade or so. Proper health workforce planning is required to ensure that a sufficient number of new doctors will become available to replace them, given that it takes about ten years to train new doctors. It is also important to take into account changes in retirement patterns of doctors, and to note that many may continue to practise beyond age 65, full time or part time, if the working conditions are adequate and if pension systems do not provide a disincentive for them to do so.

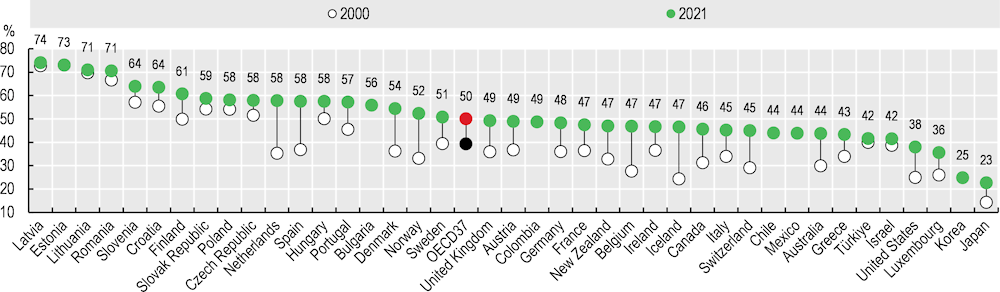

The proportion of female doctors increased in all OECD countries over the past two decades, and in 2021 half of all doctors in OECD countries were female. This proportion ranged from over 70% in Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania to 25% or less in Japan and Korea (Figure 8.7). The share of female doctors increased particularly rapidly over the past two decades in the Netherlands, Spain, Denmark and Norway – by 2021, women accounted for more than half of all doctors in these countries. Across OECD countries, this increase has been driven by growing numbers of young women enrolling in medical schools, as well as the progressive retirement of more commonly male generations of doctors. Female doctors tend to work more in general medicine and medical specialties like paediatrics, and less in surgical specialties.

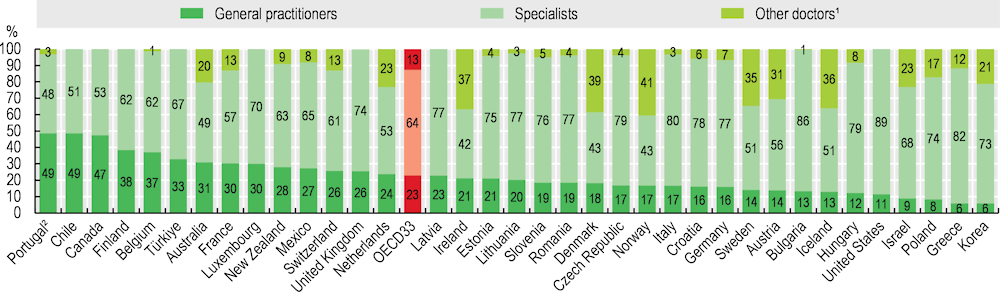

GPs (family doctors) represented less than one‑quarter (23%) of all physicians on average across OECD countries in 2021, ranging from around half in Portugal, Chile and Canada to just 6% in Korea and Greece (Figure 8.8). However, the number of GPs is difficult to compare across countries owing to variation in the ways doctors are categorised. For example, in the United States and Israel, general internal medicine doctors often play a role similar to that of GPs in other countries, yet they are categorised as specialists. General paediatricians who provide general care to children are also considered specialists in all countries, so they are not considered GPs.

Many countries have taken steps to increase the number of training places in general medicine in response to concerns about shortages of GPs. For example, in 2022, the Advisory Council on Medical Manpower Planning in the Netherlands recommended to the government that nearly half of all postgraduate residency training places should be allocated to general practice over the period 2024‑27, up from 40% in 2021 (ACMMP, 2022[1]). In France, since 2017 at least 40% of all postgraduate training places must be allocated to general medicine. In Canada, nearly 45% of residency training places filled in 2023 were in family medicine, although a number of places remained unfilled (CaRMS, 2023[2]). In many countries, attracting a sufficient number of medical graduates to fill available training places in general medicine remains a challenge, given the lower perceived prestige and remuneration (see section on “Remuneration of doctors”).