Access to medical care requires a sufficient number and proper distribution of doctors in all parts of the country. A shortage of doctors in some regions can lead to inequalities in access to care and unmet needs. Difficulties in recruiting and retaining doctors in certain regions has been an important policy issue in many OECD countries for a long time, especially in countries with remote and sparsely populated areas.

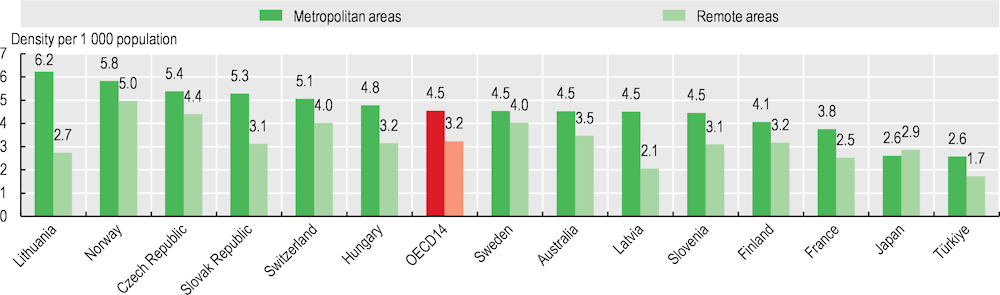

The overall number of doctors per 1 000 population varies widely across OECD countries, from 2.5 or fewer in Türkiye, Colombia and Mexico to over 5 in Greece, Portugal, Austria and Norway (see section on “Doctors (overall number)”). Beyond these cross-country differences, the number of doctors per 1 000 population also often varies widely across regions within each country. The density of doctors is generally greater in metropolitan regions, reflecting the concentration of specialised services such as surgery, and physicians’ preferences to practise in densely populated areas. In 2021, disparities in the density of doctors between metropolitan and remote regions were highest in Lithuania, Latvia and the Slovak Republic. The distribution was more equal in Norway and Sweden. In Japan, there were more doctors per population outside metropolitan areas, although the number of doctors across all regions was lower than the OECD average (Figure 8.9).

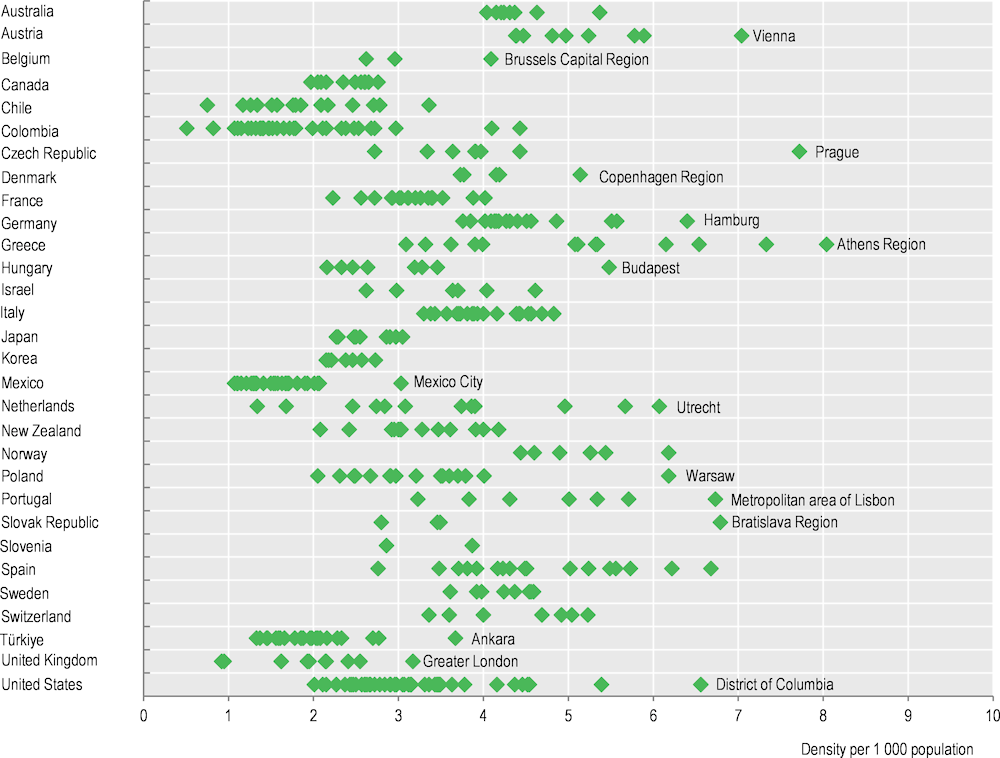

In many countries, there is a particularly high concentration of doctors in national capital regions (Figure 8.10). This is the case notably in Austria, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Greece, Hungary, Portugal, the Slovak Republic and the United States.

Doctors may be reluctant to practise in rural regions due to concerns about their professional life (including their income, working hours, opportunities for career development and isolation from peers) and social amenities (such as educational options for their children and professional opportunities for their partners). A range of policy levers can be used to influence the choice of practice location of physicians, including: 1) providing financial incentives for doctors to work in underserved areas; 2) increasing enrolment in medical education programmes of students from underserved areas or else decentralising the location of medical schools; 3) regulating the choice of practice location of doctors (for new medical graduates or foreign-trained doctors arriving in the country); and 4) reorganising service delivery to improve the working conditions of doctors in underserved areas (OECD, 2016[1]). Developments in telemedicine can also help overcome geographic barriers between patients and doctors (see section on “Digital health” in Chapter 5).

In France, successive governments have launched a number of initiatives over the past 15 years to address concerns about “medical deserts”. The main policy action to tackle this issue has been the creation of multidisciplinary health centres and homes, enabling GPs and other primary care providers to work in the same location, thereby avoiding the constraints of solo practice. By 2022, a total of 2 773 such health centres and homes were in operation. Various types of financial support are also provided for doctors to set up their practices in underserved areas. The government has also introduced monthly stipends for medical students and interns who agree to practise for a minimum duration in underserved areas on completing their training, although take‑up of this programme has remained fairly limited (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, 2021[2]).

In the Czech Republic, the Ministry of Health offers special subsidies to GPs to open offices in underserved areas, and health insurers also provide higher payments to doctors serving less densely populated regions (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, forthcoming[3]).