While it takes many years to train new doctors and nurses, recruiting them from abroad can provide a quicker solution to address immediate shortages, although it may exacerbate shortages in countries of origin. Several OECD countries, including Australia, Canada, Ireland, Israel, New Zealand, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States, have traditionally relied on international recruitment of doctors and nurses. In some countries, this reliance has increased following the pandemic (OECD, 2023[1]).

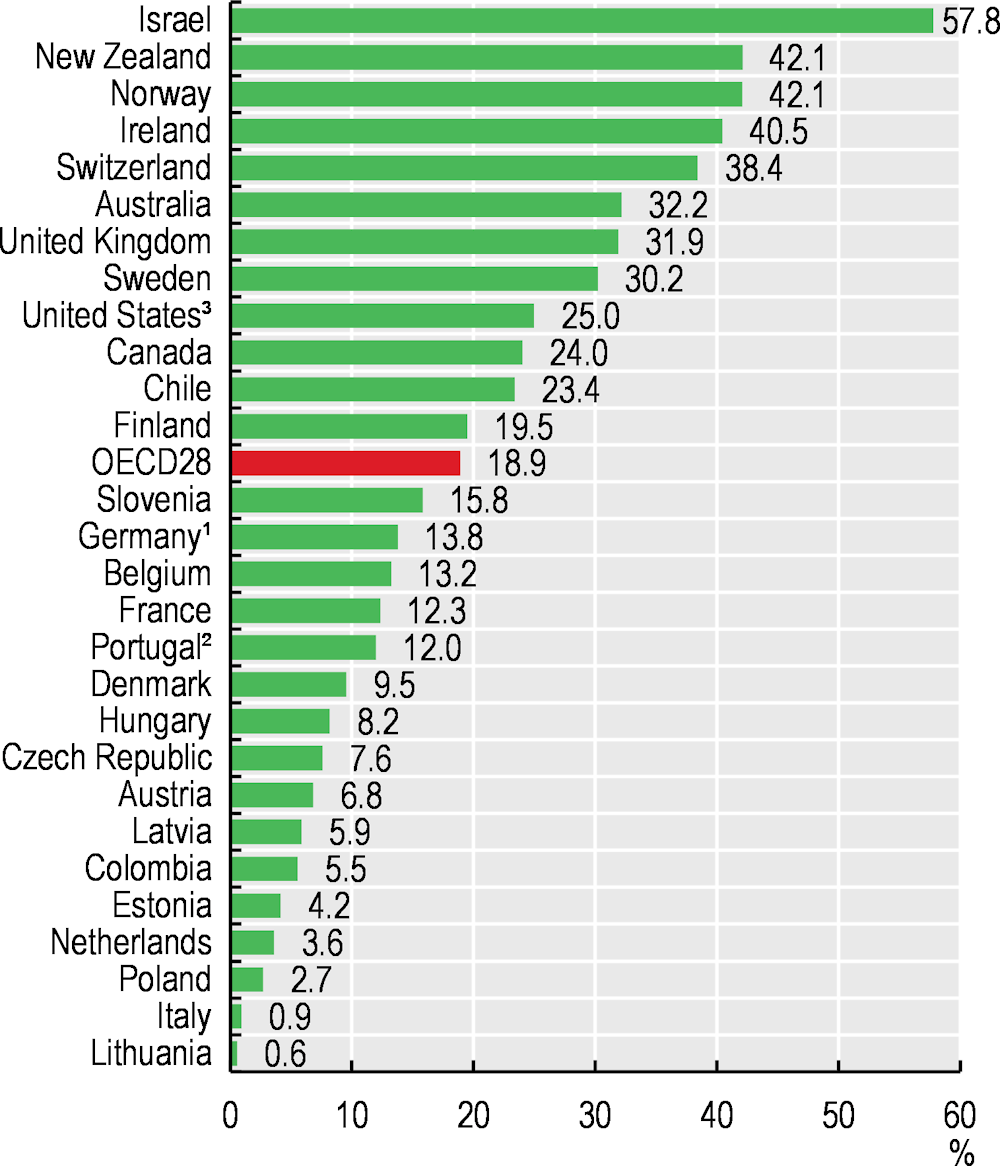

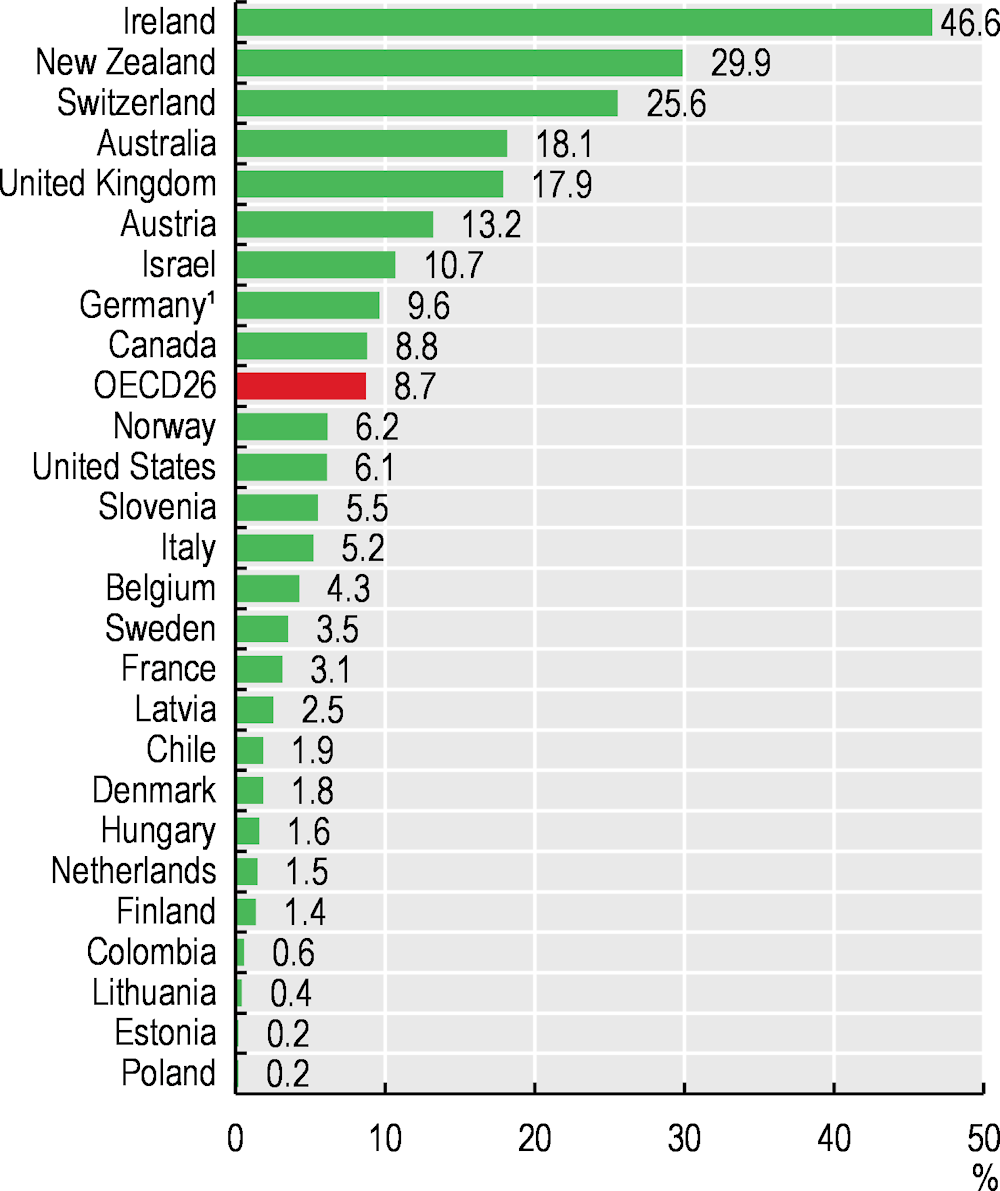

In 2021, nearly one‑fifth (19%) of doctors on average across OECD countries had obtained at least their first medical degree in another country (Figure 8.24), up from 15% a decade earlier. For nurses, on average almost 9% had obtained a nursing degree in another country in 2021 (Figure 8.25), up from 5% a decade earlier. These developments occurred in parallel with an increase in the numbers of domestically trained medical and nursing graduates in most OECD countries (see sections on “Medical graduates” and “Nursing graduates”), which indicates substantial growing demand for doctors and nurses.

In 2021, the share of foreign-trained doctors ranged from 3% or less in Lithuania, Italy and Poland to around 40% in Switzerland, Ireland, Norway and New Zealand, and nearly 60% in Israel. However, about half of foreign-trained doctors in Israel are Israeli students who went abroad to get their first medical degree before returning to Israel to complete their postgraduate residency training and work as doctors. A large proportion of foreign-trained doctors in Norway, Sweden and Finland are also doctors who were born in these countries and went abroad to study before returning to their home country. This reflects the internationalisation of medical education and a growing market for medical degrees (OECD, 2019[2]), rather than a “brain drain”.

In most OECD countries, the share of foreign-trained nurses is below 5%, and much lower than the share of foreign-trained doctors, but there are a few exceptions. Nearly 50% of nurses in Ireland are foreign-trained, while the shares are 25‑30% in New Zealand and Switzerland, and about 18% in Australia and the United Kingdom.

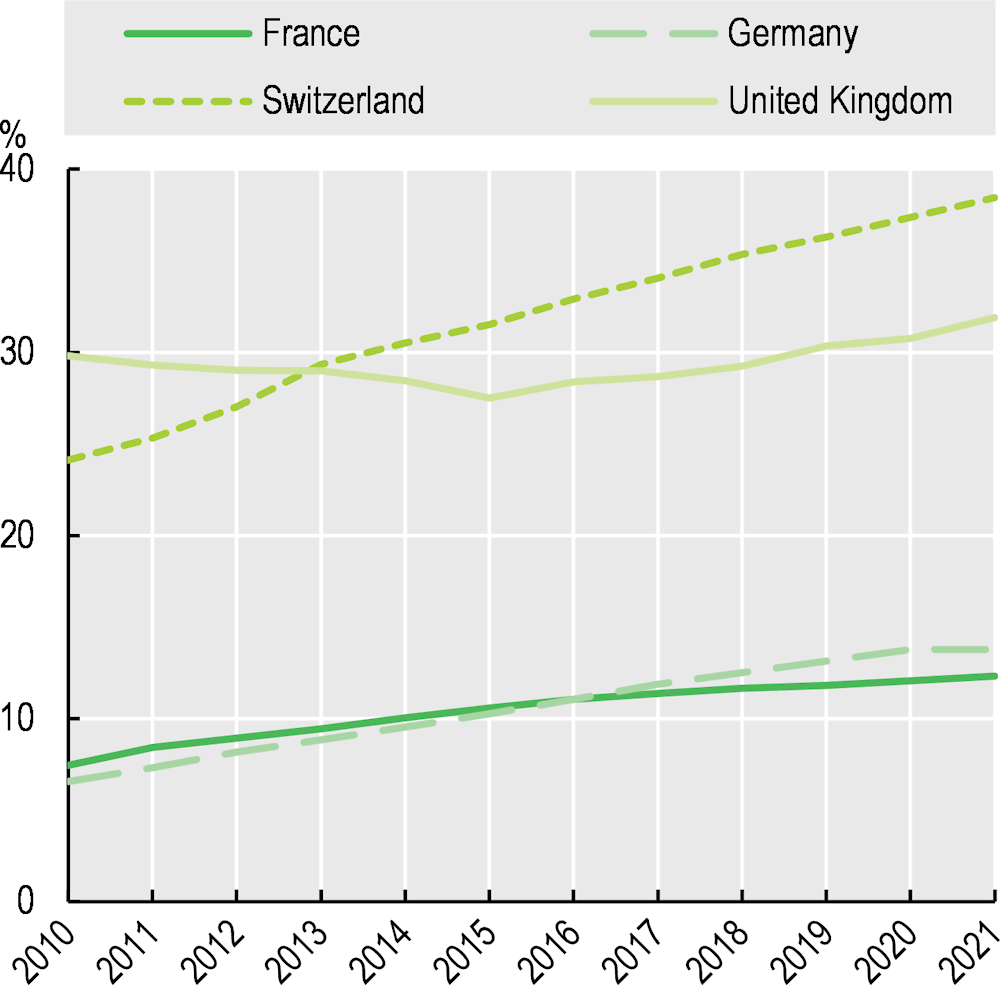

The share of foreign-trained doctors increased between 2010 and 2021 in some of the main destination countries (Figure 8.26). In the United Kingdom, the share of foreign-trained doctors fell slightly between 2010 and 2015, but it has increased in recent years to reach over 30% in 2021. In Switzerland, the share of foreign-trained doctors has increased steadily over the past decade, driven by the growing number of doctors trained in France, Germany, Austria and Italy. In France and Germany, the number and share of foreign-trained doctors has also increased steadily over the past decade, with the share nearly doubling from 7% of all doctors in 2010 to 12‑14% in 2021.

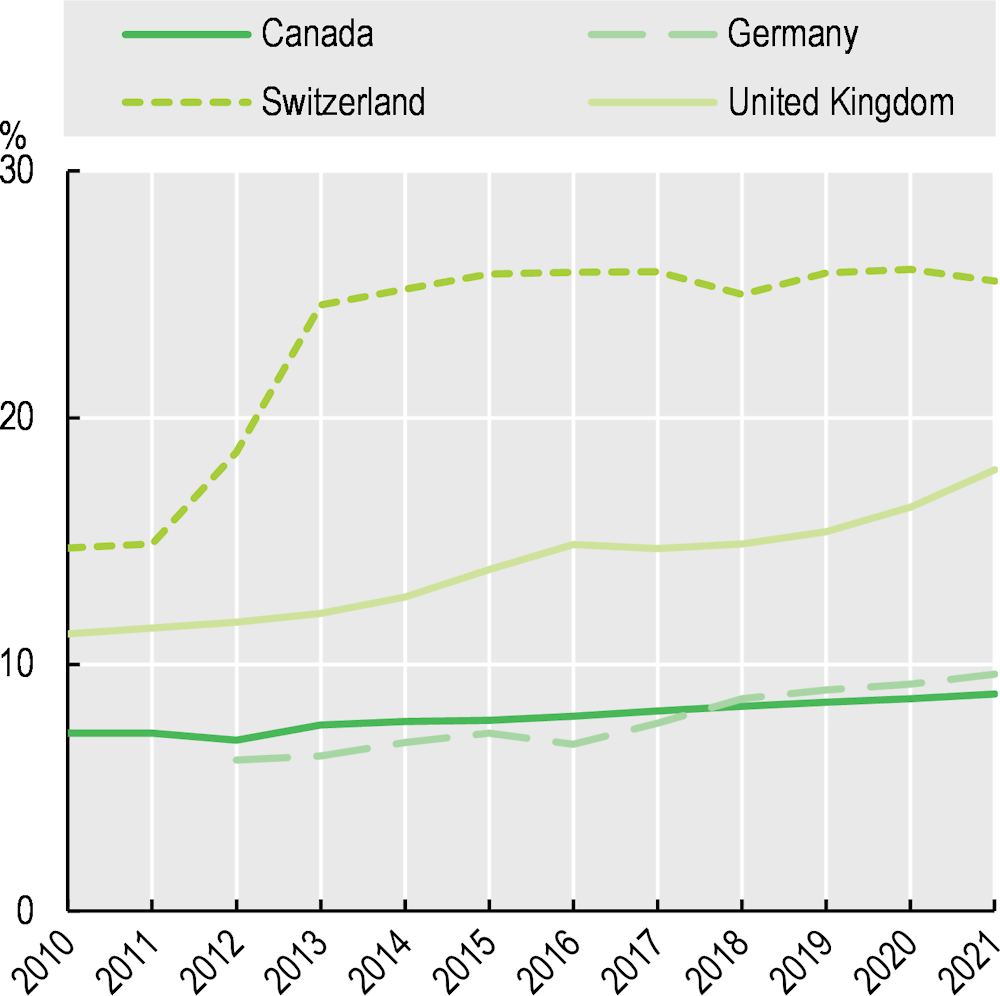

The share of foreign-trained nurses has increased substantially since 2010 in Switzerland and the United Kingdom (Figure 8.27). In Switzerland, the increase has been driven mainly by the growing number of nurses trained in France and Germany, and to a lesser extent in Italy. In the United Kingdom, international recruitment of nurses reached an all-time high in 2021/22, but the countries of origin of foreign-trained nurses in the United Kingdom have changed greatly over the past decade. Between 2010 and 2016, foreign-trained nurses were mainly recruited from EU countries. Following the Brexit vote in 2016 and the introduction of new English language test requirements for nurses, recruitment from EU countries fell greatly; however, this reduction has been more than offset by recruitment from countries outside Europe – notably the Philippines and India, but also Nigeria, Ghana and Zimbabwe (OECD, 2023[1]).

International recruitment of foreign-trained nurses has also increased over the past decade in Germany and Canada. In Canada, it reached an all-time high in 2021, and it can be expected to continue to increase further as the federal and provincial governments are encouraging more foreign nurses to come to work in the country (OECD, 2023[1]).