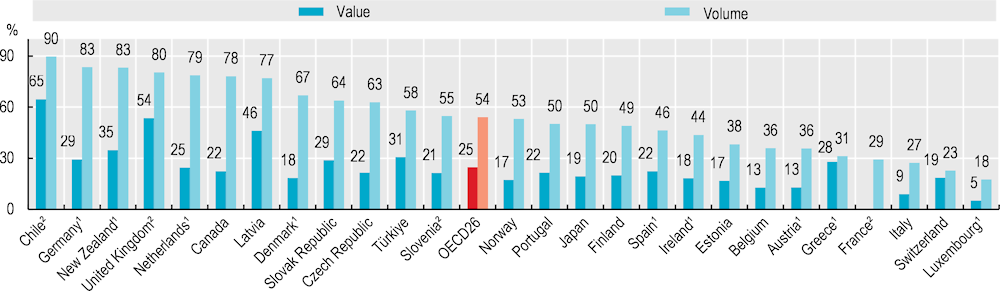

All OECD countries view generic and biosimilar markets as an opportunity to increase efficiency in pharmaceutical spending, but many do not fully exploit their potential. In 2021, generics accounted for more than three‑quarters of the volume of pharmaceuticals sold in Chile, Germany, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Canada and Latvia, but less than one‑quarter in Switzerland and Luxembourg (Figure 9.7). In value, generics accounted for more than two‑thirds of the pharmaceuticals sold in Chile in 2021, but on average only one‑quarter across OECD countries. Differences in market structures (notably the number of off-patent medicines) and prescribing practices explain some cross-country differences, but generic uptake also depends on policies (OECD, 2018[1]). In Austria, for example, generic substitution by pharmacists is not permitted, while in Luxembourg, generic substitution by pharmacists is limited to selected medicines. In some countries, such as Ireland, generic penetration is low but originators and generics may be priced at the same level.

Many countries have implemented incentives for physicians, pharmacists and patients to boost generic markets. Over the last decade, France and Hungary, for example, have introduced incentives for general practitioners to prescribe generics through pay-for-performance schemes. In Switzerland, pharmacists receive a fee for generic substitution; in France, pharmacies receive bonuses if their substitution rates are high. In many countries, third-party payers fund a fixed reimbursement amount for a given medicine, allowing the patient a choice of the originator or a generic, but with responsibility for any difference in price (OECD, 2018[1]).

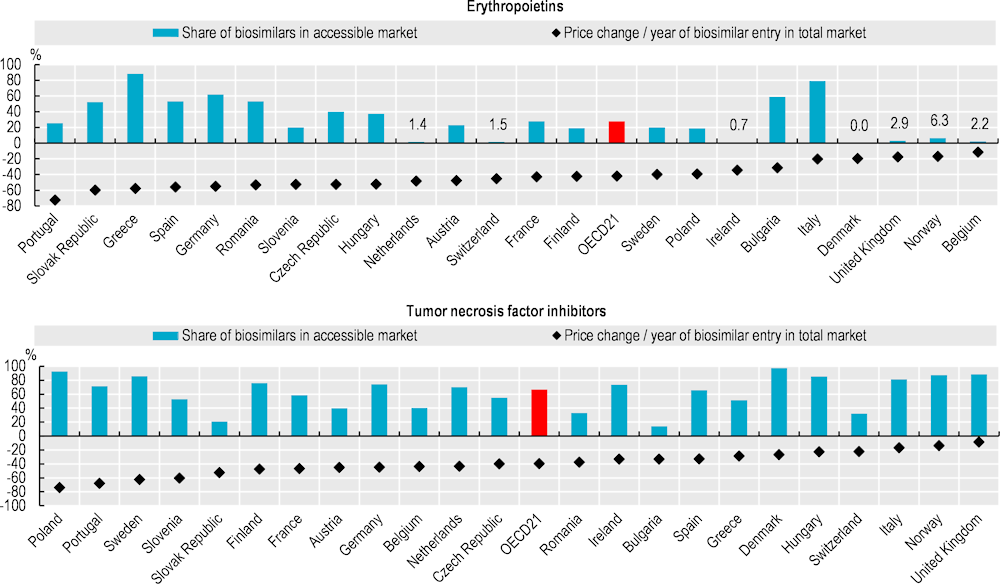

Biologicals are a class of medicines manufactured in, or sourced from, living systems such as microorganisms, or plant or animal cells. Most biologicals are very large, complex molecules or mixtures of molecules. Many are produced using recombinant DNA technology. When such medicines no longer have market exclusivity, “biosimilars” – follow-on versions of these products – can be approved. The market entry of biosimilars creates price competition, thereby improving affordability. However, the extent of biosimilar penetration in a country will depend on the reimbursement status of the biosimilar medicines. For example, in Ireland, only one of the five biosimilars licenced by the European Medicines Agency for epoetin alfa is available on the reimbursement list.

Biosimilar competition has led to both originator and biosimilar manufacturers of erythropoietins (used to treat anaemia) lowering their prices. During 2021‑22, biosimilars accounted for 28% of the volume of the “accessible market” (see the “Definition and comparability” box) for erythropoietins, on average across 21 OECD countries with comparable data. These biosimilars accounted for more than 70% of the market in Greece and Italy (Figure 9.8). In all analysed countries except Belgium, list prices for the total market of erythropoietins have fallen, with an average decrease of 42% since biosimilar entry.

For tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors also known as anti-TNF alfas (used to treat a range of autoimmune and immune‑mediated disorders), biosimilars represented over 90% of the accessible market in Denmark and Poland, but less than 40% in the Slovak Republic and Switzerland in 2021‑22 (Figure 9.8). Price reductions since biosimilar entry have been similar to those for erythropoietins. However, for both medicine classes, actual price reductions are greater than those appearing in the figures shown here. This is because these data are based on list prices: they do not take into account any confidential discounts or rebates, which can be substantial (Barrenho and Lopert, 2022[2]).