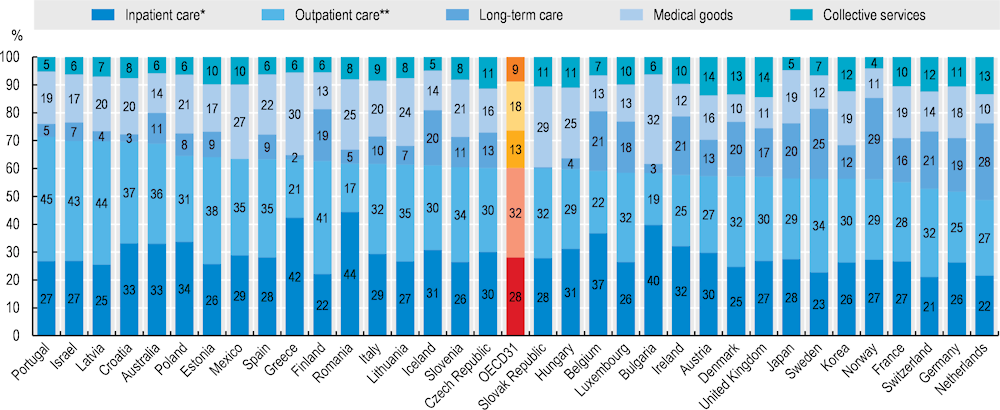

A variety of factors, from disease burden and system priorities to organisational aspects and costs determine the allocation of resources across the various types of healthcare services. For all OECD countries, curative and rehabilitative care services make up the bulk of health spending and are primarily delivered through inpatient and outpatient services – accounting for 60% of all health spending in 2021 (Figure 7.15). Medical goods (mostly pharmaceuticals) made up a further 18%, followed by long-term care services, which in 2021 averaged around 13% of health spending. Administration and overall governance of the health system, together with preventive care account for the remaining 9% of health spending.

In 2021, Belgium and Greece reported the highest share of total health spending allocated to inpatient services, at around 40%. At the other end of the scale, many of the Nordic countries as well as Switzerland and the Netherlands had a much lower proportion of spending on inpatient services – at around 20% of overall health spending.

Outpatient care forms a broad category covering generalist and specialist outpatient services, dental care, but also homecare and ancillary services. Taking all these categories together, spending on outpatient care services accounted for around 45% of all health spending in Portugal, Latvia and Israel compared to an OECD average of 32%. Given the relative importance of inpatient care delivery, Greece and Belgium allocated a comparably low proportion on outpatient services, with less than a quarter of all health spending.

The third largest health spending category is medical goods. Differences in prices for international goods such as pharmaceuticals tend to show less variation across countries than for locally produced services. As a result, spending on medical goods (including pharmaceuticals) in lower-income countries often accounts for a higher share of health spending relative to services. For example, in 2021, expenditure on medical goods represented around 30% of all health spending in Mexico, the Slovak Republic and Greece. By contrast, with only accounting for one‑tenth of overall health spending, these shares were much lower in Denmark, Norway, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

Spending on long-term care services accounted for 13% of health spending on average in 2021, but this figure hides big differences across OECD countries. In countries with formal arrangements such as in Norway, Sweden and the Netherlands, a quarter or more of all health spending is for long-term care services. However, a more informal long-term care sector exists in many Southern, Central and Eastern European countries including Hungary, Latvia, Greece and the Slovak Republic, and in Latin American countries such as Mexico, where spending on long-term care is much lower – typically around 5% or less.

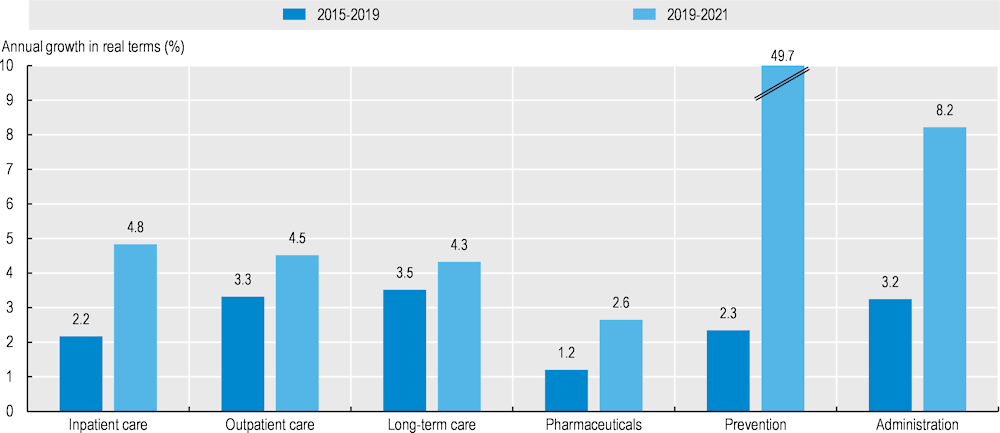

The COVID‑19 pandemic drastically changed health spending patterns in many countries resulting in notable differences in the average annual spending growth per capita in the years preceding the pandemic (2015‑19) compared to during the pandemic (Figure 7.16). Between the years 2015 and 2019, annual per capita spending growth for retail pharmaceuticals (1.2%) and inpatient care (2.2%) was relatively moderate, whereas the average yearly increases for spending on outpatient care, long-term care and administration per capita were more pronounced, standing between 3‑3.5%.

The pandemic triggered exceptional spending growth across all healthcare functions (Figure 7.16). Most notably, spending on preventive care increased by nearly 50% per year (up from 2.3% pre‑pandemic), with countries dedicating significant resources to testing, tracing, surveillance, and public information campaigns related to the pandemic and the roll-out of the vaccination campaigns in 2020 and 2021. Annual per capita spending growth on inpatient care more than doubled, driven by expenses for additional staff and input costs (e.g. personal protective equipment) and substantial subsidies for hospitals. With around 8% annually, spending on health system administration also recorded strong growth between 2019 and 2021. Some of this increase can be explained by the additional resources required to manage national COVID‑19 responses strategies. Preliminary data for 2022 suggests that some of the most recent increases will be short-lived and a normalisation of growth rates can be expected with as countries transition out of the acute phase of the pandemic.