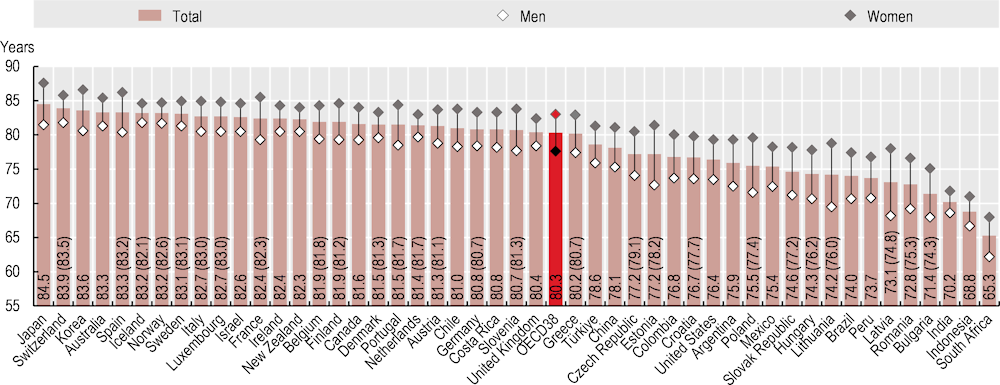

While life expectancy has increased in all OECD countries over the past half century, progress was stalling in the decade prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic, and many countries experienced outright drops in life expectancy during the pandemic. In 2021 life expectancy at birth was 80.3 years on average across OECD countries (Figure 3.1). Japan, Switzerland and Korea led a large group of 27 OECD member countries in which life expectancy at birth exceeded 80 years. A second group, including the United States, had life expectancy between 75 and 80 years. Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary and the Slovak Republic had the lowest life expectancy among OECD countries, at less than 75 years. Provisional Eurostat data for 2022 point to a strong rebound in life expectancy in many Central and Eastern European countries, but a more mixed picture for other European countries, including reductions of half a year or more in Iceland, Finland and Norway.

In all partner countries, life expectancy remained below the OECD average in 2021, with levels lowest in South Africa (65.3 years), Indonesia (68.8) and India (70.2). Still, levels have been converging rapidly in most of these countries in recent decades.

Women continue to live longer than men in all OECD member and partner countries. This gender gap averaged 5.4 years across OECD countries: life expectancy at birth for women was 83 years, compared to 77.6 years for men. These gender differences in life expectancy are due in part to greater exposure to risk factors among men – particularly greater tobacco consumption, excessive alcohol consumption and less healthy diets. Men are also more likely to die from violent deaths, such as suicide and accidents. The gender gap has, however, narrowed over time. Gender differences in life expectancy are especially marked in Central and Eastern European countries: Latvia, Lithuania and Poland in particular have gaps of 8 or more years. In these countries, gains in longevity for men over the past few decades have been much more modest. Gender gaps are relatively narrow in Iceland and Norway, at 3 years or less.

COVID‑19 has had a major impact on life expectancy owing to the exceptionally high number of deaths this pandemic has caused. Indeed, OECD countries recorded around 6 million excess deaths in 2020‑22, compared to the average number of deaths over the five preceding years (see section on “Trends in all-cause mortality”).

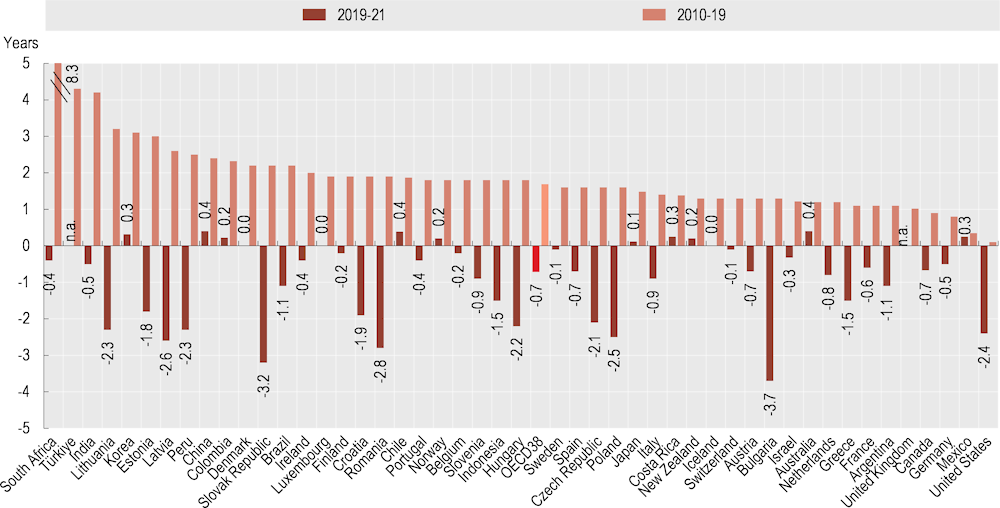

Prior to the pandemic, life expectancy increased in all OECD member and partner countries between 2010 and 2019, with an average increase of 1.7 years (Figure 3.2). However, many of these gains were wiped out during the pandemic. Between 2019 and 2021, life expectancy decreased by 0.7 years on average across OECD countries. Reductions were highest in Central and Eastern European countries and the United States (no recent data available for Türkiye and the United Kingdom). Among accession countries, Bulgaria, Romania and Peru also reported large reductions. Seven OECD countries lost as many – or more – years of life expectancy during the first two years of COVID‑19 as they had gained in the past decade: the Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Latvia, Poland, the Slovak Republic and the United States. This was also the case in accession countries Argentina, Bulgaria, Croatia and Romania.

However, life expectancy between 2019 and 2021 did not decrease in all OECD countries. Denmark, Luxembourg and Iceland recorded no change, while Australia, Chile, Korea, Costa Rica, Mexico, Colombia, Norway, New Zealand and Japan recorded increases in life expectancy.

Even before COVID‑19, gains in life expectancy had been slowing down markedly in a number of OECD countries over the last decade. This slowdown was most marked in the United States, France, the Netherlands, Germany and the United Kingdom. Longevity gains were slower for women than men in almost all OECD countries. The causes of this slowdown in life expectancy gains over time are multi-faceted (Raleigh, 2019[1]). Principal among them is slowing improvements in reducing death rates of heart disease and stroke. Rising levels of obesity and diabetes, as well as population ageing, have made it difficult for countries to maintain previous progress in cutting deaths from such circulatory diseases.