End-of-life care refers to the care provided to people who are near the end of life. It involves all the services providing physical, emotional, social and spiritual support to the dying person, including management of pain and mental distress. Emotional support and bereavement care for the dying person’s family are also part of end-of-life care. Because of population ageing and an associated increase in prevalence of chronic conditions across OECD countries, the number of people in need of end-of-life care is growing and expected to reach 10 million people by 2050, up from 7 million in 2019. However, fewer than half of those who need end-of-life care are currently receiving it, meaning that many people die without adequate care (OECD, 2023[1]). Measuring the quality of end-of-life care is not straightforward, but exploring where people die and what type of care they receive in their last months of life are considered good proxies.

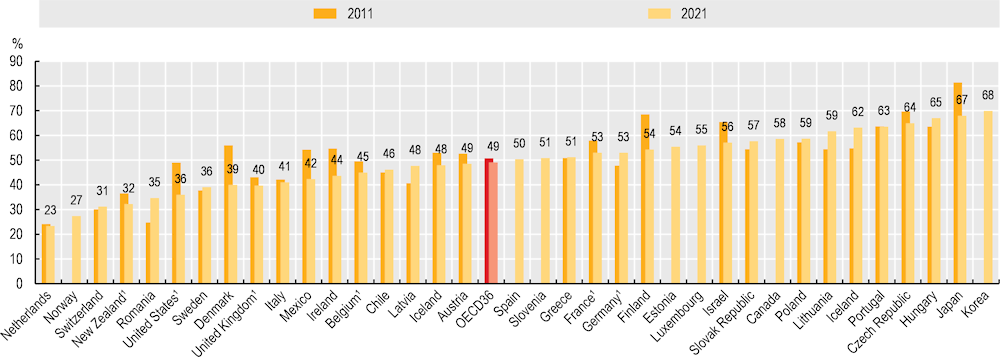

End-of-life care can be delivered in a number of settings, including hospitals, hospices, nursing homes and patients’ homes. Although personal characteristics, beliefs and other cultural factors can influence preferences for care at the end of life, existing literature shows that most people would prefer to spend the end of their lives in their homes. Hospitals are the most common place of death across OECD countries, although the share of deaths happening in hospitals has decreased in many countries in the past decade. As of 2021, 50% of deaths across 35 OECD countries occurred in a hospital. The Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland and New Zealand record the lowest shares, with only around one‑third of deaths or fewer happening in hospitals. This is likely to be linked to the role of nursing homes, hospices or other LTC facilities, which in Sweden, Switzerland and the Netherlands represent the most prevalent place of death (OECD, 2023[1]). In the Czech Republic, Hungary, Japan and Korea, 65% of deaths or more take place in hospitals.

The share of deaths occurring in hospitals decreased between 2011 and 2021 in most countries, with the largest reductions in Denmark (16 percentage points), Japan and Finland (14 percentage points), the United States (13 percentage points), Mexico (12 percentage points) and Ireland (11 percentage points) (Figure 10.26). This change was driven in part by an increase in the share of deaths taking place at home during the COVID‑19 pandemic due to a lack of service availability during the crisis, yet this trend had already started before the pandemic. A decrease in the share of deaths in hospitals does not necessarily translate into better quality of end-of-life care if it is not supported by adequate care available at home.

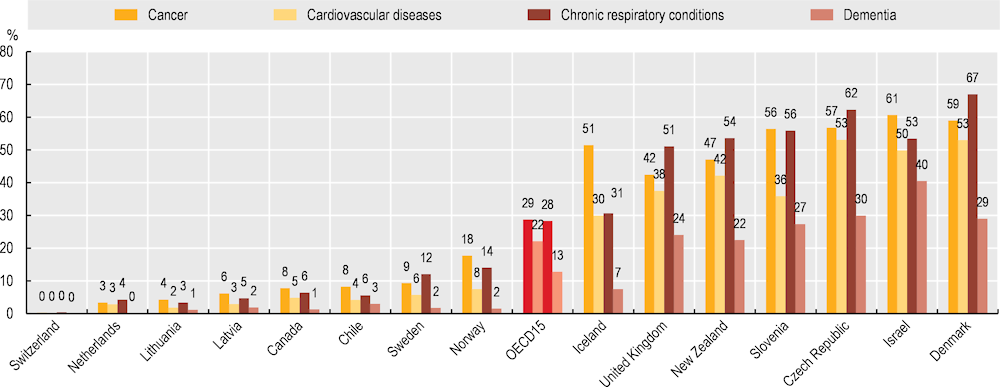

Understanding when people are approaching the end of life can be difficult. Not recognising when death is near can result in overtreatment and delays in palliative care, and people might receive aggressive care until the very end of their lives, even when it is not likely to provide any curative benefit. Delayed referral to palliative care can compromise the end-of-life experience (Sallnow et al., 2022[2]). The care people receive in the last months of life varies widely across OECD countries. In 8 out of 15 countries for which data are available, only a minority of people experienced more than one unplanned/urgent admission during the last 30 days of their life in 2021, ranging from nearly none (0.2%) in Switzerland to 11% in Norway. New Zealand, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, Israel and Denmark recorded much higher shares of deceased people who had experienced more than one unplanned/urgent admission during the last 30 days of their life, ranging from 45% in New Zealand to 59% in Israel.

Furthermore, in at least six OECD countries the share of people experiencing more than one unplanned/urgent inpatient admission in the last 30 and last 180 days of life are very similar, suggesting that unplanned/urgent admissions are more likely to happen in the last month of life. Unplanned admissions at the end of life also vary within countries. Across all OECD countries with available data, people who died due to cancer and chronic respiratory conditions were more likely to experience at least one unplanned/urgent admission in the last 30 days of life, compared to people who died due to cardiovascular diseases and dementia (Figure 10.27).