In recent decades, the share of the population aged 65 and over has doubled on average across OECD countries, increasing from less than 9% in 1960 to 18% in 2021. Declining fertility rates and longer life expectancy (see section on “Life expectancy at birth” in Chapter 3) have meant that older people make up an increasing proportion of the population in OECD countries. Across the 38 OECD member countries, more than 242 million people were aged 65 and over in 2021, including more than 64 million who were at least 80 years old. These demographic developments highlight the importance of ensuring that health systems are equipped to meet the changing needs of an older population.

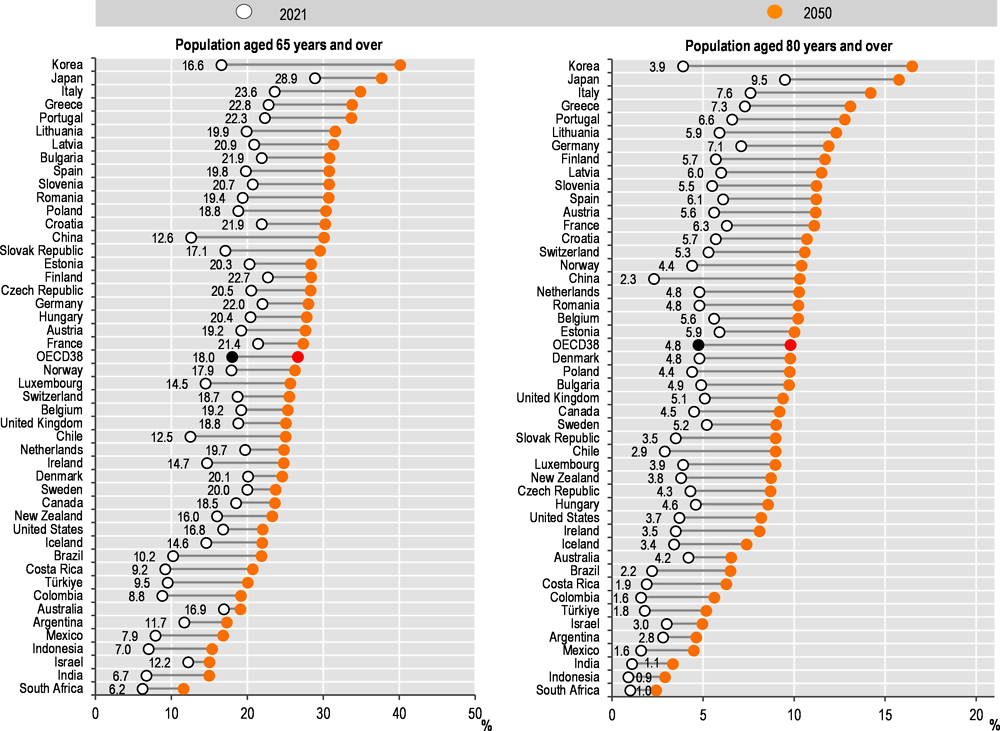

Across OECD member countries on average, the share of the population aged 65 and over is projected to continue increasing in the coming decades, rising from 18% in 2021 to 27% by 2050 (Figure 10.1). In five countries (Korea, Japan, Italy, Greece and Portugal), the share of the population aged 65 and over will exceed one‑third by 2050. At the other end of the spectrum, the population aged 65 and over in Israel, Mexico, Australia and Colombia will represent less than one‑fifth of the population in 2050, owing to higher fertility and migration rates.

While the rise in the share of the population aged 65 and over has been striking across OECD countries, the increase has been particularly rapid among the oldest group – people aged 80 and over. Between 2021 and 2050, the share of the population aged 80 and over is predicted to double on average across OECD member countries, from 4.8% to 9.8%. At least one in ten people may be 80 and over in nearly half (18) of these countries by 2050, while in five countries (Korea, Japan, Italy, Greece and Portugal), more than one in eight people may be 80 and over.

While most OECD partner countries have a younger age structure than many member countries, population ageing will nonetheless occur rapidly in the coming years, and sometimes at a faster pace than among member countries. In China, the share of the population aged 65 and over will increase much more rapidly than in OECD member countries – more than doubling from 12.6% in 2021 to 30.1% in 2050. The share of the Chinese population aged 80 and over will rise even more quickly, increasing more than four‑fold from 2.3% in 2021 to 10.3% in 2050. Partner country Brazil – whose share of the population aged 65 and over was only around half the OECD average in 2021 – will see similarly rapid growth, with nearly 22% of the population projected to be aged 65 and over by 2050. The speed of population ageing has varied markedly across OECD countries, with Japan in particular experiencing rapid ageing over the past three decades. In the coming years, Korea is projected to undergo the most rapid population ageing among OECD member countries, with the share of the population aged 80 and over nearly quintupling – from below the OECD average in 2021 (3.9% versus 4.8%) to well above it (16.5% versus 9.8%) by 2050. Among OECD partner countries, the speed of ageing has been slower than among member countries, although rapid ageing in large countries including Brazil and China will accelerate in the coming decades.

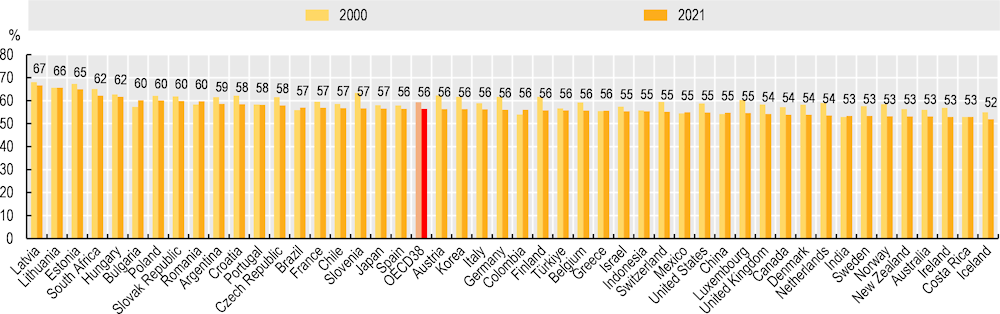

Because of longer life expectancy than men, women tend to predominate among the older age cohorts. On average across OECD countries, women represented 56% of the population aged 65 and over in 2021, a slight decrease from 59% in 2000 (Figure 10.2). In Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia, women made up more than 65% of the population aged 65 and over in 2021, while at the other end of the spectrum, they made up just 52% of the population aged 65 and over in Iceland.

One of the major implications of rapid population ageing is the decline in the potential supply of labour in the economy, despite recent efforts by countries to extend working lives. Moreover, in spite of the gains in healthy life expectancy seen in recent years (see section on “Life expectancy and healthy life expectancy at age 65”), health systems will need to adapt to meet the needs of an ageing population, which are likely to include greater demand for labour-intensive long-term care (LTC) and a greater need of integrated, person-centred care. Between 2015 and 2030, the number of older people in need of care around the world is projected to increase by 100 million (ILO/OECD, 2019[1]). Countries such as the United States are already facing shortages of LTC workers, and in the coming years more will find themselves under pressure to recruit and retain skilled LTC staff (see section on “Long-term care workers”). More recently, the COVID‑19 crisis has put the spotlight on the workforce shortcomings of the LTC sector. While the total number of LTC workers has increased in a number of countries, it has not kept pace with population ageing. As a result, the supply of LTC workers per 100 elderly people (aged 65 and over) has stagnated in most countries since 2011 (OECD, 2020[2]).