Comparisons of health spending reflect differences in the prices of healthcare goods and services, and the quantity of care that individuals are using (“volume”). Decomposing health spending into the two components gives policy makers a better understanding of what is driving spending differences.

Cross-country comparisons require spending to be expressed in a common currency, and the choice of conversion measure can heavily impact the results and interpretation (OECD/Eurostat, 2012[1]). One approach relies on converting local currencies using foreign exchange rates but this is not ideal because of their volatility. Moreover, for goods and services that are not traded internationally such as healthcare, market exchange rates do not reflect the relative purchasing power of currencies in their national markets. Another approach uses purchasing power parities (PPPs) which are available at an economy-wide level, industry level, and for selected spending aggregates. Actual Individual Consumption (AIC) PPPs – comprising all goods and services consumed by individuals – are the most widely used conversion rates for health spending (see indicator “Health expenditure per capita). However, using AIC PPPs means that the resulting measures not only reflect variations in the volume of healthcare goods and services, but also any variations in the prices of healthcare goods and services relative to prices of all other consumer goods and services across countries.

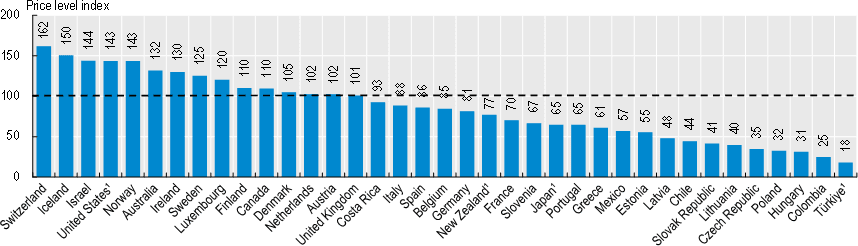

Figure 7.7 shows health-specific price levels based on a representative basket of healthcare goods and services for each OECD country. Switzerland and Iceland have the highest health prices in the OECD – on average the same basket of goods and services would cost 62% and 50% more than the OECD average, respectively. Healthcare prices also tend to be relatively high in Israel and the United States. In contrast, prices for the same mix of healthcare goods and services in Japan, Portugal and Slovenia are around two‑thirds of the OECD average. The lowest healthcare prices in the OECD are in Türkiye, at 18% of the OECD average.

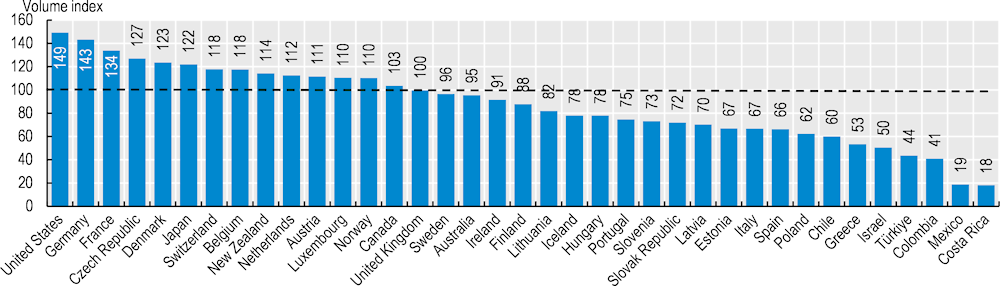

Removing the health price component from expenditure gives a measure of the amount of healthcare goods and services consumed by the population (“the volume of healthcare”). Comparing relative levels of health expenditures and volumes provides a way to look at the contribution of volumes and prices. Volumes of healthcare use vary less than health expenditure (Figure 7.8). The United States remains the highest consumer of healthcare in volume terms, 49% higher than the OECD average. The lowest per capita healthcare volumes in the OECD are in Costa Rica and Mexico, at around one fifth of the OECD average. Differences in the per capita volume of care is influenced by the age and disease profile of a population, the organisation of service provision, the use of prescribed pharmaceuticals, as well as issues with access leading to lower levels of care being used.

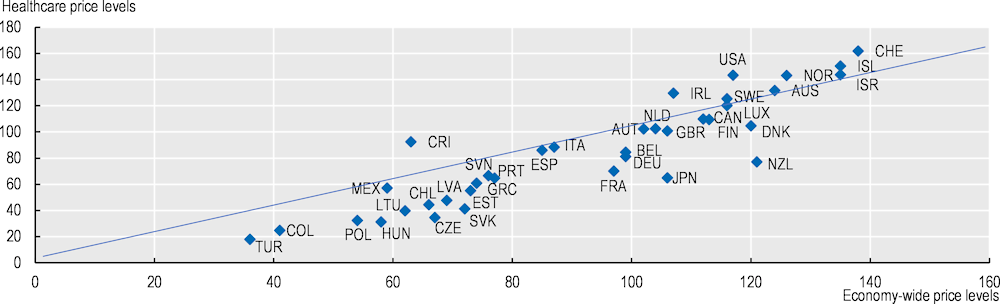

There is a strong correlation between prices in the health sector and economy-wide prices. But while internationally traded goods tend to equalise in price between trading partners, services (such as healthcare) are typically purchased locally, with, for example, higher wages in wealthier countries leading to higher service prices. Comparing price levels in the health sector and in the economy relative to the OECD average, variation in health prices is greater than that in economy-wide prices (Figure 7.9). Countries with relatively low economy-wide prices tend to have health price levels that are even lower than in the general economy, and countries with high economy-wide prices typically having health prices that are higher than in the general economy. Yet not all higher income countries with high general prices have more expensive healthcare. In France and Germany, for example, general price levels are close to the OECD average, but healthcare prices are 30% and 20% lower respectively than the OECD average. This may reflect in part policy decisions to regulate healthcare prices.