All OECD countries offer some degree of formal LTC to assist people in need of care in their daily activities. Care is provided by LTC workers, who are defined as paid staff – typically nurses and personal carers – providing care and/or assistance to people limited in their daily activities at home or in institutions, excluding hospitals.

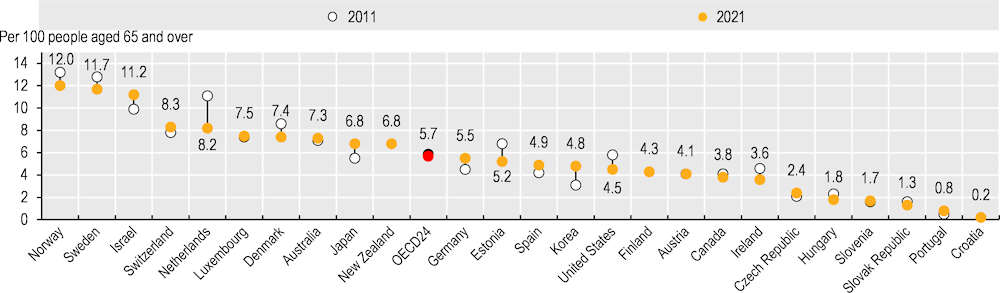

In 2021, there were on average 5.7 LTC workers per 100 people aged 65 and over across the 23 OECD countries for which data were available, ranging from 12 in Norway to 0.8 in Portugal (Figure 10.18). While almost all countries have seen an increase in LTC workers in terms of headcounts, the number of LTC workers per 100 people aged 65 and over has, on average, slightly decreased over time, from 5.9 per 100 in 2011 to 5.7 per 100 in 2021. This trend was observed in just under half of countries with time trend data, with decreases over 20% in the Netherlands, Estonia, the United States, Hungary and Ireland. This is indicative of increased supply of LTC workers not keeping pace with greater demand caused by rapidly ageing populations. In contrast, 13 of the OECD countries with available data saw an increase in LTC workers per 100 population aged 65 and over, with the largest increases in Portugal and Korea.

The demand for LTC workers will increase in the years to come due to population ageing and changing patterns of informal care. At the same time, the LTC sector is facing longstanding difficulties in meeting demands for supply. The COVID‑19 pandemic has exacerbated these shortages. The LTC sector is characterised by poor working conditions, including low wages, high physical and mental risks, non-standard employment, as well as low recognition (OECD, 2023[1]).

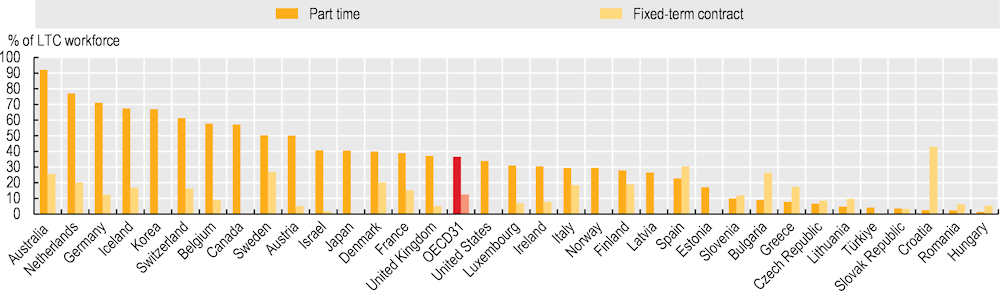

LTC workers are predominantly women: a share of 80% or higher are female, and earn on average 20% less than the economy-wide average wage (OECD, 2023[1]). Non-standard employment is common in the LTC sector. In 31 OECD countries that reported data, the share of LTC workers in part-time employment amounted to 37% on average, with 66% of the LTC workforce in Korea, Iceland, Germany, the Netherlands and Australia working in part-time arrangements. Moreover, every eighth worker across 31 OECD countries worked on a fixed-term contract basis (Figure 10.19). This is particularly common in Australia, Spain and Sweden, where more than one‑quarter of the LTC workforce works under fixed-term contracts.

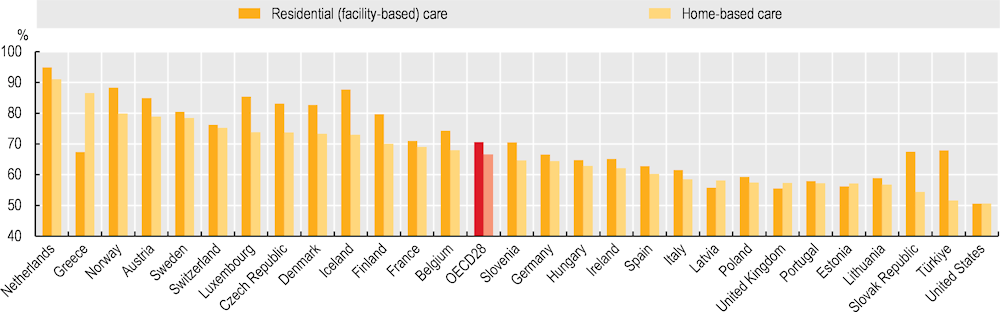

Low salaries among personal care workers have long been identified as a major challenge for recruitment and retention in the sector. Across 28 OECD countries in 2018, both care workers in facilities and those working in personal homes made substantially less than the average wage, with workers in facilities earning just 71% of the average gross hourly wage, and home‑based care workers earning just 67% of the average gross hourly wage (Figure 10.20). Wages were highest in the Netherlands, where care workers earned more than 90% of the country’s average gross hourly wage regardless of the location of their work, and lowest in the United States, where care workers earned just half (51%) of the country’s average gross hourly wage.

Educational and training requirements are particularly low for personal care workers, while a mismatch between education and skills needed – such as specific geriatric training, health monitoring and co‑ordinating care – can negatively affect the quality of care delivered. Beyond low salaries and employment instability, limited access to training and education and career prospects might lower the attractiveness of the LTC profession. Several countries have introduced policies to improve the skills match between LTC workers and the tasks they perform to address this (OECD, 2020[2]).