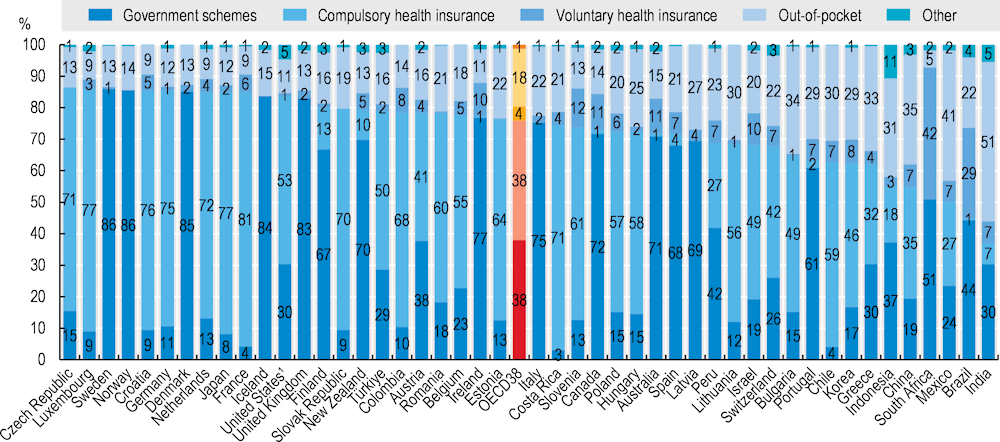

There is a variety of financing arrangements through which individuals or groups of the population obtain healthcare. Government financing schemes, on a national or sub-national basis or for specific population groups, entitle individuals to healthcare based on residency and form the principal mechanism to cover healthcare costs in close to half of OECD countries. The other main method of financing is some form of compulsory health insurance (managed through public or private entities). Spending by households (out-of-pocket spending), both on a fully discretionary basis and part of some co-payment arrangement, can constitute a significant part of overall health spending. Finally, voluntary health insurance, in its various forms, can also play an important funding role in some countries.

Compulsory or automatic coverage, through government schemes or health insurance, forms the bulk of healthcare financing in OECD countries. Taken together, three‑quarters of all healthcare spending in 2021 was covered through these types of mandatory financing schemes (Figure 7.10). Central, regional, or local government schemes in Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Sweden and the United Kingdom accounted for 80% or more of national health spending. In Germany, Japan, France and Luxembourg, three‑quarters or more of spending was covered through a type of compulsory health insurance scheme. In the United States, federal and state programmes covered around a third of all US healthcare spending in 2021. Another 50% of expenditure is classified under compulsory insurance schemes, covering very different arrangements including federal health insurance schemes, such as Medicare, but also private health insurance, which is considered compulsory under the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

Out-of-pocket payments financed just under one‑fifth of all health spending in 2021 in OECD countries, with this share broadly decreasing as GDP increases. Households accounted for 30% or more of all spending in Mexico (41%), Greece (33%), Chile and Lithuania (both 30%), while in France, the Netherlands and Luxembourg, out-of-pocket spending was below 10%.

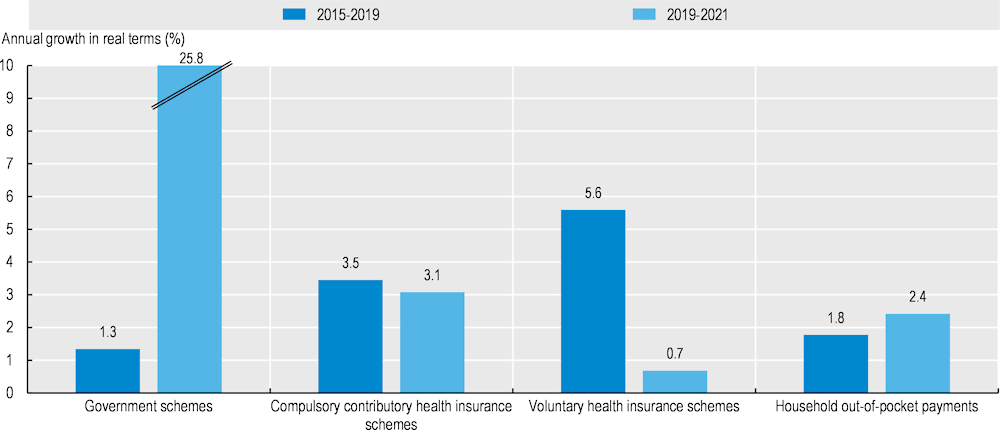

In the years preceding the COVID‑19 pandemic (2015‑19), per capita spending by compulsory health insurance and voluntary health insurance schemes grew by 3.5% and 5.6% on average per year, respectively, above the growth rate of total health expenditure over the same period (2.6%) (Figure 7.11). Meanwhile, spending by government schemes averaged 1.3% annual growth. Moreover, with moves towards universal health coverage, health expenditure financed by out-of-pocket payments (1.8%) grew below the rate of overall health expenditure.

The spending trajectory of the various financing schemes changed with the onset of the COVID‑19 pandemic in 2020 (Figure 7.11). While spending growth of compulsory health insurance schemes remained largely unchanged during the 2019‑21 period, spending by government schemes increased by an annual average of 26% as significant resources were made available to track the virus, increase system capacity, provide subsidies to health providers and eventually roll out COVID‑19 vaccination campaigns. The growth in spending by government schemes was particularly high in countries where access to services is generally obtained via health insurance, including Chile, Colombia, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia. In those countries, government schemes generally do not play a large purchasing role in the health system, but they have assumed important financing responsibilities during the pandemic. In Colombia, for example, a newly established central government fund to finance COVID‑19 response measures allocated approximately 40% of its resources to the health sector for testing, treatment, and vaccination (Vammalle and Córdoba Reyes, 2022[1]).

Meanwhile, spending by voluntary insurance saw a trend reversal in the period between 2019 and 2021 compared to 2015‑19, as a result of postponement and reduced demand for elective healthcare services and the partial non-availability of services. In Ireland, for example, private hospitals agreed to provide treatment capacity for public patients during the peak waves of the pandemic, thereby reducing service availability for private payers (including those willing to use voluntary private insurance).