A fundamental principle underpinning all health systems across OECD countries is to provide access to high-quality care for the whole population, irrespective of their socio‑economic circumstances. Yet access can be limited for several reasons, including limited availability or affordability of services. Policies therefore need to ensure an adequate supply and distribution of health workers and healthcare services throughout the country, and address any financial barriers to care (OECD, 2019[1]; 2023[2]).

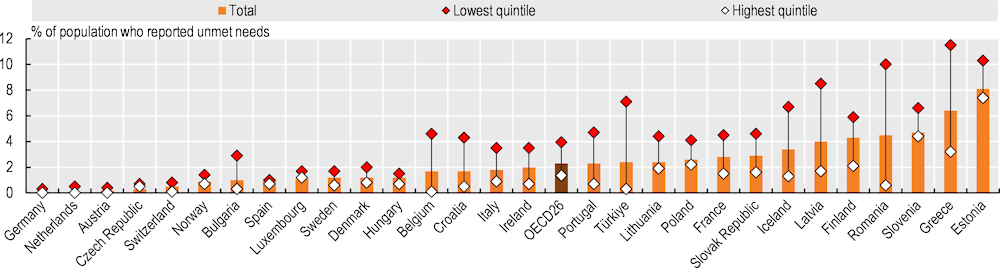

On average across 26 OECD countries with comparable data, only 2.3% of the population reported that they had unmet medical care needs due to cost, distance or waiting times in 2021 (Figure 5.4). However, over 5% of the population reported unmet care needs in Estonia (8.1%) and Greece (6.4%), while in Germany, the Netherlands, Austria and the Czech Republic, fewer than 0.5% of the population reported unmet needs for medical care. Socio‑economic disparities are significant: people in the lowest income quintile were three times more likely to report unmet medical care needs than those in the highest quintile in 2021, on average across 26 OECD countries. This income gradient exists in all analysed countries; it was largest in Greece, Latvia and Türkiye (and accession country Romania), with a difference of over 6 percentage points in the population reporting unmet needs between the lowest and highest income quintiles. In Greece and Estonia, more than one in ten people in the lowest income quintile reported unmet medical care needs.

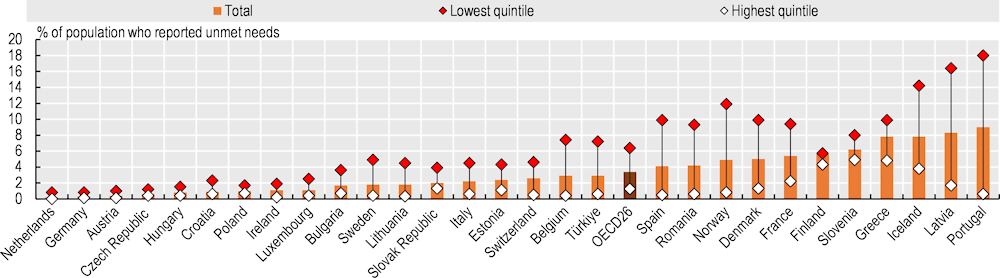

Reported unmet needs are generally larger for dental care than for medical care (Figure 5.5). This reflects the fact that dental care is less well covered by public schemes than medical care in most OECD countries, so people often must pay out of pocket or purchase additional private health insurance (see section on “Extent of healthcare coverage”). More than 7% of people in Portugal, Latvia, Iceland and Greece reported unmet dental care needs in 2021, compared to fewer than 0.5% in the Netherlands, Germany and Austria. In all analysed countries, the burden of unmet needs for dental care falls disproportionately on people on lower incomes. This was most evident in Portugal and Latvia, where more than 16% of people in the lowest income quintile reported forgoing needed dental care in 2021, compared to fewer than 2% in the highest quintile. Recently, Portugal has aimed to improve access to dental care by creating dental health offices within public primary healthcare facilities.

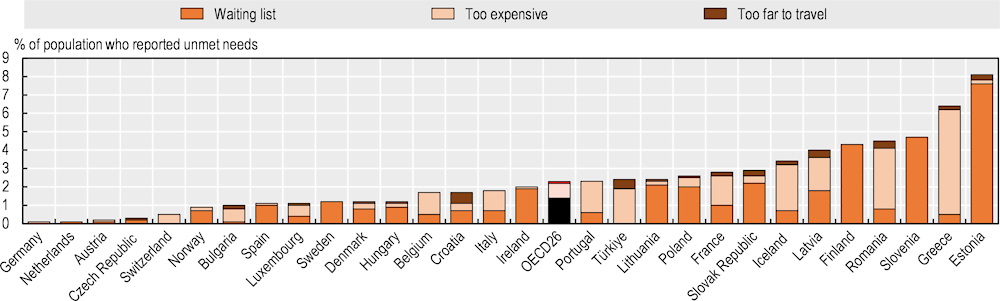

The main reason cited for unmet needs for medical care was typically waiting times, with 1.4% of people reporting this issue in 2021, on average across 26 OECD countries (Figure 5.6). In Estonia, Slovenia and Finland, more than 4% of the population cited waiting times as a barrier. Cost was also cited as an important barrier to access, and was the main reason for unmet needs in Greece, Iceland, Türkiye and Latvia, and accession country Romania. Distance to travel was also cited as a barrier, but less frequently than waiting times or cost.

Unmet medical care needs due to cost have generally fallen in most countries since 2011 (other than in Portugal, Luxembourg and Denmark). However, unmet medical care needs due to waiting times have often increased since 2011 – particularly in Slovenia, Estonia, Ireland and the Slovak Republic. Some of these countries have introduced initiatives to reduce waiting times. In Estonia, for example, the national e‑booking system now includes a function where patients can select a treatment service and the system automatically searches for an appointment time that matches their preferences. This system should help the government track which health services have longer waiting lists and analyse the reasons (OECD/European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, forthcoming[3]).