Early diagnosis, together with healthy lifestyles (see Chapter 4 “Risk factors for health”), is key to tackling cancer. Screening is considered a cost-effective way to reduce the burden of breast, cervical and colorectal cancer. Most OECD countries have programmes for breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening in place for target populations, but for each cancer type, the target population, screening frequency and methods can vary across countries.

In the case of breast cancer, WHO recommends organising population-based mammography screening programmes, and emphasises the importance of helping women to make an informed decisions about their participation, based on both benefits and risks (WHO, 2014[1]). OECD countries typically provide screening checks every two years to women aged 50‑69.

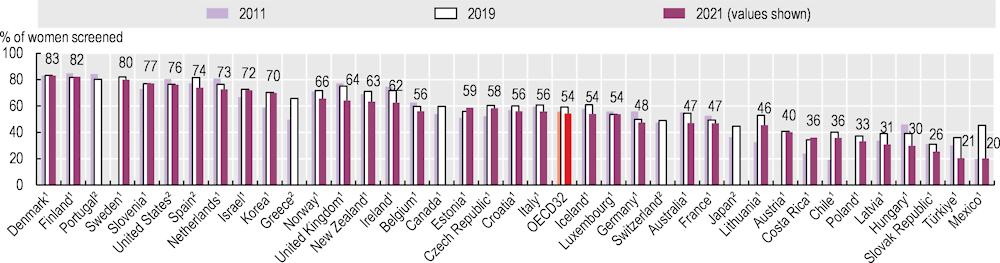

Figure 6.3 shows the proportion of women aged 50‑69 who had a mammography examination in the two years preceding 2011, 2019 and 2021. The screening rate varies widely across OECD countries; for the latest period it reached a high of 83% of the target population in Denmark, and a low in Mexico and Türkiye, where fewer than 25% of women in the target age group had a mammography examination during the past two years.

While cancer screening rates were generally increasing prior to the COVID‑19 pandemic, they dropped at its onset. Cancer screening programmes were often paused to prioritise urgent care needs, and many people also delayed seeking healthcare – including cancer screening – to reduce the risk of COVID‑19 transmission (OECD, 2021[2]). In most OECD countries, cancer screening rates in 2021 were still lower than those in 2019.

With regards to breast cancer screening, the average screening rate in 2021 was 5 percentage points lower than in 2019 (Figure 6.3). However, this masks variations in screening rate change over time across countries. While most OECD countries saw uptake increase again after the initial phase of the pandemic, and some countries such as Costa Rica, Estonia, Finland and Slovenia attained higher rates in 2021 than in 2019, around one‑third of OECD countries continued to see screening rates decrease in 2021.

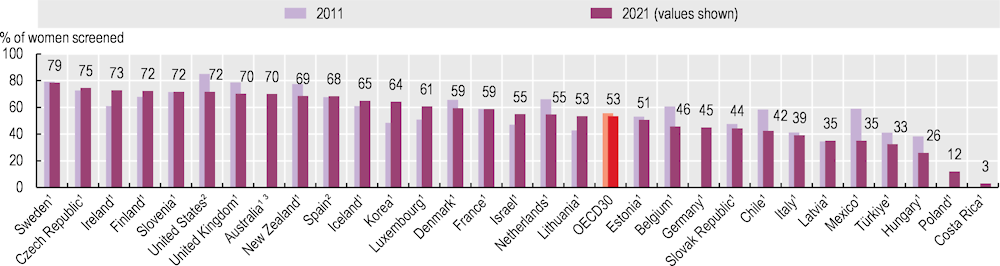

In OECD countries, cervical cancer screening is often provided every three years to women aged 20‑69, although the target population and screening frequency may change with the integration of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination programmes in most countries. WHO recommends that countries strive to reach an incidence rate lower than four new cases of cervical cancer per 100 000 women each year. To attain this goal, WHO recommends a 90% HPV vaccination coverage rate among girls by the age of 15, 70% coverage of cervical cancer screening at ages 35 and 45, and improvement of treatment coverage (treating 90% of women with pre‑cancer and managing 90% of women with invasive cancer) (WHO, 2020[3]).

Figure 6.4 shows wide variations in the proportions of women aged 20‑69 who had been screened for cervical cancer within the preceding three years across countries. In 2021, the highest rate was 79% in Sweden, followed by 75% in the Czech Republic, while the lowest rate was 3% in Costa Rica.

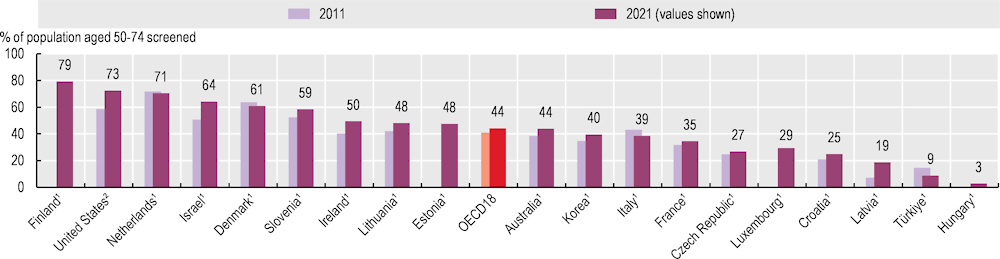

Compared to breast and cervical cancers, fewer OECD countries have nationwide screening programmes for colorectal cancer. Country guidelines typically recommend biennial faecal occult blood tests for people in their 50s and 60s, but some countries use other methods, including colonoscopy exams, leading to differences in recommended screening frequencies, making comparisons of screening coverage across countries challenging.

Figure 6.5 shows coverage rates in colorectal cancer screening programmes based on national screening programme protocols. The proportion varies from a high of 79% in Finland, followed by the United States (73%) and the Netherlands (71%), to a low of less than 3% in Hungary.

Cervical and colorectal cancer screening uptake was also adversely impacted by the COVID‑19 pandemic, but delayed screening – and subsequent late diagnosis and treatment – may lead to poorer outcomes for patients. To minimise these consequences, many OECD countries have made additional efforts to increase screening uptake and to reduce the backlog of cancer diagnosis. Trends in screening uptake since the pandemic are not necessarily consistent across different types of cancer screening within the same country, suggesting a need for specific strategies to improve coverage of each cancer screening.